Astronomers using the James Webb Space Telescope have detected unexpected high-energy ultraviolet radiation near several infant stars, a finding that challenges current models of star formation. The discovery, made in a nearby stellar nursery, suggests an unknown internal process is at work within these developing systems.

Key Takeaways

- The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) observed unexpected ultraviolet (UV) radiation around five protostars in the Ophiuchus molecular cloud.

- Protostars, or infant stars, are generally considered too young and cool to produce such high-energy radiation themselves.

- Researchers ruled out nearby massive stars as the source, concluding the UV radiation must originate from a process internal to the protostars.

- This discovery could require significant updates to scientific models explaining how stars are born and develop.

A Cosmic Nursery's Surprise

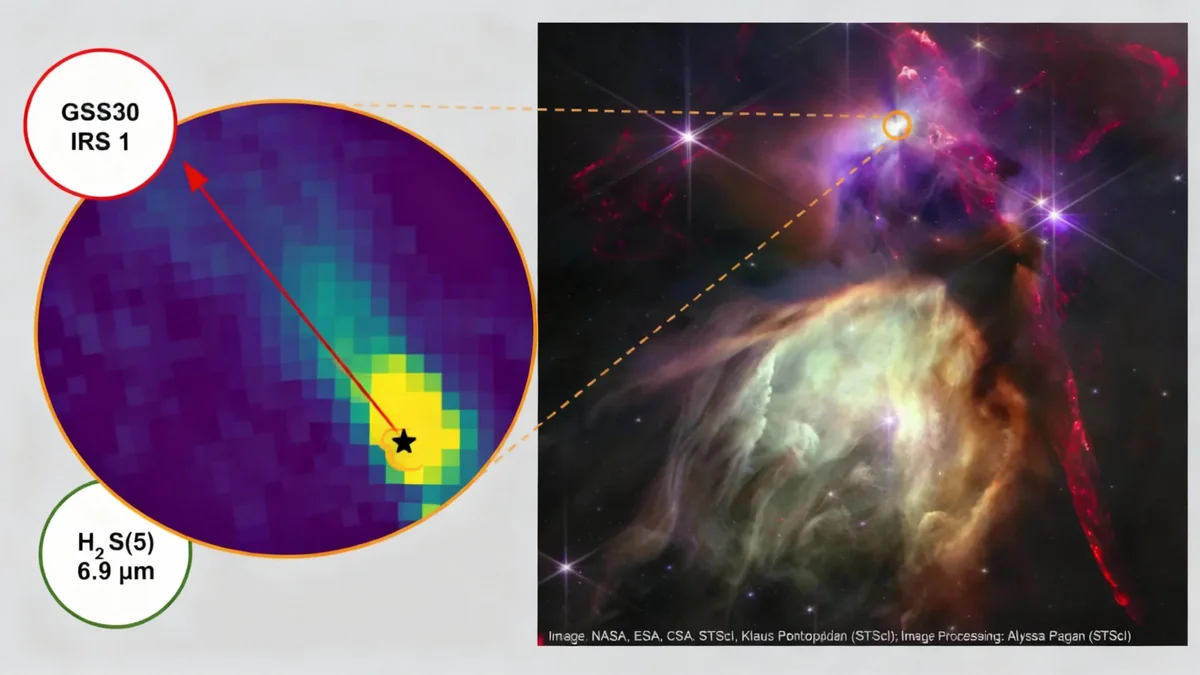

Deep within the Ophiuchus molecular cloud, a sprawling stellar nursery located approximately 450 light-years from Earth, the James Webb Space Telescope has uncovered a celestial puzzle. Scientists studying five protostars—the earliest stage in a star's life—found the distinct signature of high-energy ultraviolet light where none was expected.

Protostars are formed from the gravitational collapse of dense clouds of gas and dust. They are still actively gathering mass from a surrounding envelope of material, a process that precedes the nuclear fusion that will eventually power them as adult stars. Because of their early stage of development, they are not yet hot enough to generate intense UV radiation on their own.

"We wanted to take a closer look at protostars, young stars that are still forming deep inside their parent molecular clouds," explained Iason Skretas, a researcher from the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy who was part of the team.

What Are Protostars?

Protostars represent the embryonic phase of a star's existence. They are dense, warm cores of gas and dust that have not yet ignited nuclear fusion. During this stage, which can last for hundreds of thousands of years, they grow by accreting material from a surrounding disk and launching powerful jets, or outflows, of matter from their poles.

The Unexpected Glow

The research team focused their investigation on the powerful outflows of material ejected by these young stars. As these jets slam into the surrounding molecular cloud, they create shockwaves that heat the gas, causing molecules to glow. The team used Webb's Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) to analyze the light from molecular hydrogen, the most abundant molecule in the universe.

The data revealed clear evidence of UV radiation influencing the hydrogen emissions. This presented a significant question for the astronomers.

"This is the first surprise. Young stars are not capable of being a source of radiation; they cannot 'produce' radiation. So we should not expect it," said Agata Karska from Nicolaus Copernicus University in Poland. "And yet we have shown that UV occurs near protostars. Where did it come from?"

The team considered two primary possibilities for the source of this mysterious light: an external source from neighboring stars or an internal source originating from the protostar system itself.

Ruling Out External Sources

The Ophiuchus cloud is home to several massive, hot stars known as B-type stars, which are known to emit powerful UV radiation. A logical first step was to determine if these larger stars were illuminating their smaller, developing neighbors.

To test this hypothesis, the astronomers carefully selected five protostars located at varying distances from these massive B-type stars. If the radiation were external, the protostars closer to the massive stars should show stronger effects from the UV light, while those farther away would show weaker effects. The team also calculated how much UV radiation would be absorbed by the dense dust surrounding each protostar.

Molecular Hydrogen as a Thermometer

Molecular hydrogen (H₂) is difficult to detect directly in cold space clouds. However, when it is heated by shockwaves or radiation, it emits light at specific infrared wavelengths. The JWST is exceptionally sensitive to this light, allowing scientists to use the molecule's emissions as a tool to measure the temperature and conditions in regions where stars are forming.

"Using these two methods, we showed that ultraviolet radiation, in terms of external conditions, varies significantly between our protostars, and therefore we should see differences in molecular emission," Skretas noted. "As it turns out, we don't see them."

The observations were remarkably consistent across all five protostars, regardless of their proximity to the massive stars. This uniformity allowed the team to confidently reject the idea that the UV radiation was coming from an external source.

An Internal Cosmic Engine

With external sources ruled out, the evidence points to an internal origin. The UV radiation must be generated by physical processes occurring within the immediate vicinity of each protostar.

Scientists are now exploring several potential mechanisms:

- Accretion Shocks: As gas and dust from the surrounding cloud fall onto the protostar at high speeds, the impact could create powerful shockwaves that generate UV light.

- Jet Shocks: The jets of material being blasted away from the protostar could contain internal shocks close to their launch point, producing the observed radiation.

"We can say with certainty that UV radiation is present in the vicinity of the protostar, as it undoubtedly affects the observed molecular lines," Karska stated. "Therefore, its origin has to be internal."

The team's findings, published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics, open a new line of inquiry into the energetic environments of the youngest stars. Future JWST observations will examine not only the gas but also the dust and ice in the Ophiuchus region, providing a more complete picture of the physical and chemical processes that govern the birth of stars and, eventually, planets.