Astronomers have discovered that the most powerful supermassive black holes can stop star formation not only in their own galaxy but also in neighboring galaxies up to a million light-years away. This finding, based on data from the James Webb Space Telescope, suggests that galactic evolution is a far more interconnected process than previously understood.

The research challenges the long-held belief that galaxies evolve in relative isolation, revealing that the immense energy from an active black hole can sterilize its cosmic neighborhood, preventing the birth of new stars across vast distances.

Key Takeaways

- Active supermassive black holes, known as quasars, can suppress star formation in galaxies a million light-years away.

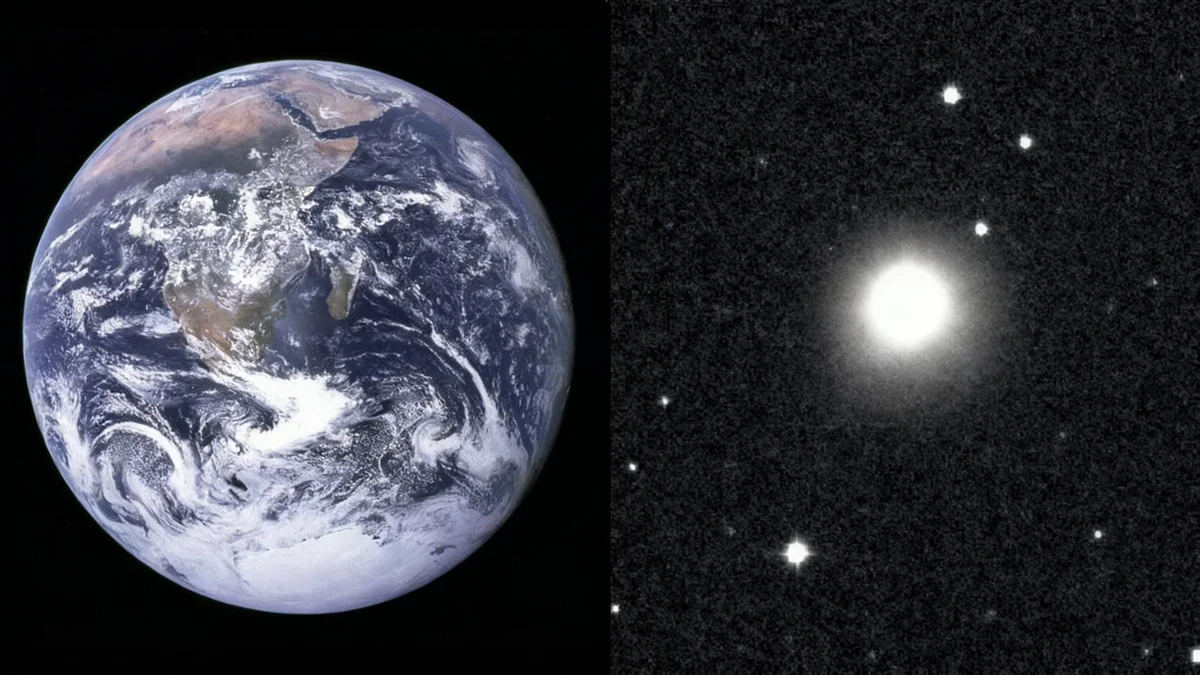

- The James Webb Space Telescope provided evidence by observing the environment around a very bright quasar named J0100+2802.

- Intense radiation from the quasar heats and disperses the gas clouds needed for stars to form.

- This discovery suggests galaxies exist in a connected "ecosystem" where a dominant black hole can affect its entire region.

A Predator in the Cosmic Ecosystem

For years, scientists have known that an active supermassive black hole can regulate star birth within its host galaxy. When these cosmic giants feed on surrounding gas and dust, they unleash enormous amounts of energy. This process can either blow away the raw materials for new stars or heat them to temperatures where they can no longer collapse and ignite.

However, new research indicates this influence extends much further. A team led by Yongda Zhu of the University of Arizona found that this galactic "death" can spread to other galaxies. "Traditionally, people have thought that because galaxies are so far apart, they evolve largely on their own," Zhu stated. "But we found that a very active, supermassive black hole in one galaxy can affect other galaxies across millions of light-years."

"An active supermassive black hole is like a hungry predator dominating the ecosystem. Simply put, it swallows up matter and influences how stars in nearby galaxies grow."

This concept introduces the idea of a galactic ecosystem, where the actions of one massive object can have profound consequences for its neighbors, much like how changes in one part of an Earth-based ecosystem can impact another.

The JWST Uncovers a Cosmic Puzzle

The investigation centered on observations made by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). Scientists noticed a curious pattern: the most powerful quasars—the intensely bright cores of galaxies powered by feeding black holes—appeared to be strangely isolated. This was unexpected, as large galaxies are typically found in clusters.

"We were puzzled," Zhu explained. The team began to suspect the neighboring galaxies were present but were simply difficult to see. They theorized that the quasar's intense energy had suppressed recent star formation, making the galaxies much dimmer and harder to detect.

What is a Quasar?

A quasar is the extremely luminous center of a distant galaxy, powered by a supermassive black hole feeding on matter. As gas and dust spiral into the black hole, friction heats the material to incredible temperatures, causing it to glow so brightly that it can outshine all the stars in its host galaxy combined. Not all supermassive black holes are active; the one at the center of our Milky Way, Sagittarius A*, is currently quiet.

To test this idea, the researchers focused on one of the brightest quasars ever discovered, J0100+2802. This object existed when the universe was less than a billion years old and is powered by a black hole with a mass approximately 12 billion times that of our sun.

Evidence of a Galactic Dead Zone

Using the JWST's sensitive instruments, the team searched for a specific chemical signature—ionized oxygen—in the galaxies surrounding J0100+2802. Ionized oxygen is a reliable indicator of recent and active star formation.

The results were clear. Galaxies located within a one-million-light-year radius of the quasar showed significantly less ionized oxygen than galaxies situated further away. This provided direct evidence that star formation was being actively suppressed in the quasar's immediate cosmic neighborhood.

The Mechanism of Suppression

The intense heat and radiation from a quasar's accretion disk are powerful enough to travel across intergalactic space. This energy strikes the vast, cold clouds of molecular hydrogen in nearby galaxies. The radiation splits the hydrogen molecules, preventing the gas from cooling and collapsing under gravity—the essential first step in creating a new star.

"For the first time, we have evidence that this radiation impacts the universe on an intergalactic scale," Zhu said. The findings confirm that the influence of these cosmic behemoths is not confined to their own galactic borders.

Rethinking How Galaxies Evolve

This discovery fundamentally alters the scientific understanding of galaxy evolution. It suggests that the development of galaxies is not solely an internal process but is also shaped by powerful external forces from their neighbors. The most massive black holes can act as regional regulators, dictating the pace of star birth across their entire cluster.

The team plans to expand its research by examining other quasar fields to see if this effect is a common phenomenon in the early universe. Understanding these large-scale interactions is crucial for piecing together the history of cosmic structures, including our own Milky Way galaxy.

"Understanding how galaxies influenced one another in the early universe helps us better understand how our own galaxy came to be," Zhu concluded. "Now we realize that supermassive black holes may have played a much larger role in galaxy evolution than we once thought." The research was published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.