A new study suggests that the existence of life on Earth may be the result of an exceptionally rare chemical balance struck during the planet's formation 4.6 billion years ago. Researchers have identified a narrow "chemical Goldilocks zone" for oxygen that allowed Earth to retain the essential elements needed for biology to emerge.

This finding could significantly refine the search for extraterrestrial life, suggesting that a planet's internal chemistry is just as critical as its distance from a star.

Key Takeaways

- A recent study proposes that a precise level of oxygen during Earth's formation was critical for life.

- This specific oxygen balance allowed phosphorus and nitrogen, two elements essential for biology, to remain in the planet's crust and mantle.

- Too little oxygen would have trapped phosphorus in the core, while too much would have caused nitrogen to be lost to space.

- The research suggests scientists should focus the search for alien life on planets orbiting stars with a chemical makeup similar to our Sun.

The Elemental Balancing Act

For decades, the search for life beyond Earth has focused on the "habitable zone," the orbital region around a star where a planet's surface temperature could allow for liquid water. However, new research published in the journal Nature Astronomy indicates that water alone is not enough. The key may lie in a planet's earliest moments, during its molten phase of core formation.

During this chaotic period, heavy elements like iron sink to form a planet's core, while lighter materials rise toward the surface. According to the study, the amount of oxygen present during this process acts as a master controller, dictating where other crucial elements end up.

The two elements in question are phosphorus and nitrogen. Phosphorus is a fundamental component of DNA and cell membranes, while nitrogen is essential for proteins and other biological molecules. Without them readily available on a planet's surface, life as we know it could not begin.

Beyond the Habitable Zone

The traditional habitable zone, or "Goldilocks zone," refers to the distance from a star where a planet is not too hot and not too cold for liquid water to exist. This new research introduces a chemical Goldilocks zone, an internal property of the planet itself, which may be a more fundamental requirement for life.

A Chemical Sweet Spot

Using geochemical models, researchers from ETH Zurich simulated planetary formation under various oxygen conditions. Their findings revealed an incredibly narrow window for success.

The study outlines two critical failure points:

- Too little oxygen: If oxygen levels are too low, phosphorus develops a strong affinity for iron. It bonds with the sinking metal and gets dragged down into the planet's core, permanently removing it from the surface where life could access it.

- Too much oxygen: If oxygen levels are too high, nitrogen becomes more volatile and is easily lost from the atmosphere into space.

Earth, it seems, formed under conditions that were just right. The planet's oxygen levels were perfectly balanced, allowing both phosphorus and nitrogen to remain in the mantle and crust, creating a chemical inventory ripe for biology.

"During the formation of a planet's core, there needs to be exactly the right amount of oxygen present so that phosphorus and nitrogen can remain on the surface of the planet," stated Craig Walton, the study's lead author.

A Precise Calculation

The models developed by the researchers show that Earth sits squarely within this precise range of medium-level oxygen. A slight deviation in either direction during its formation could have rendered our world a sterile rock, despite having liquid water.

Refining the Search for Alien Life

This discovery has profound implications for how astronomers search for life on exoplanets. It suggests that simply finding an Earth-sized planet in the habitable zone of its star is not a guarantee of habitability. The planet must also possess the correct internal chemical makeup, a property much harder to detect from light-years away.

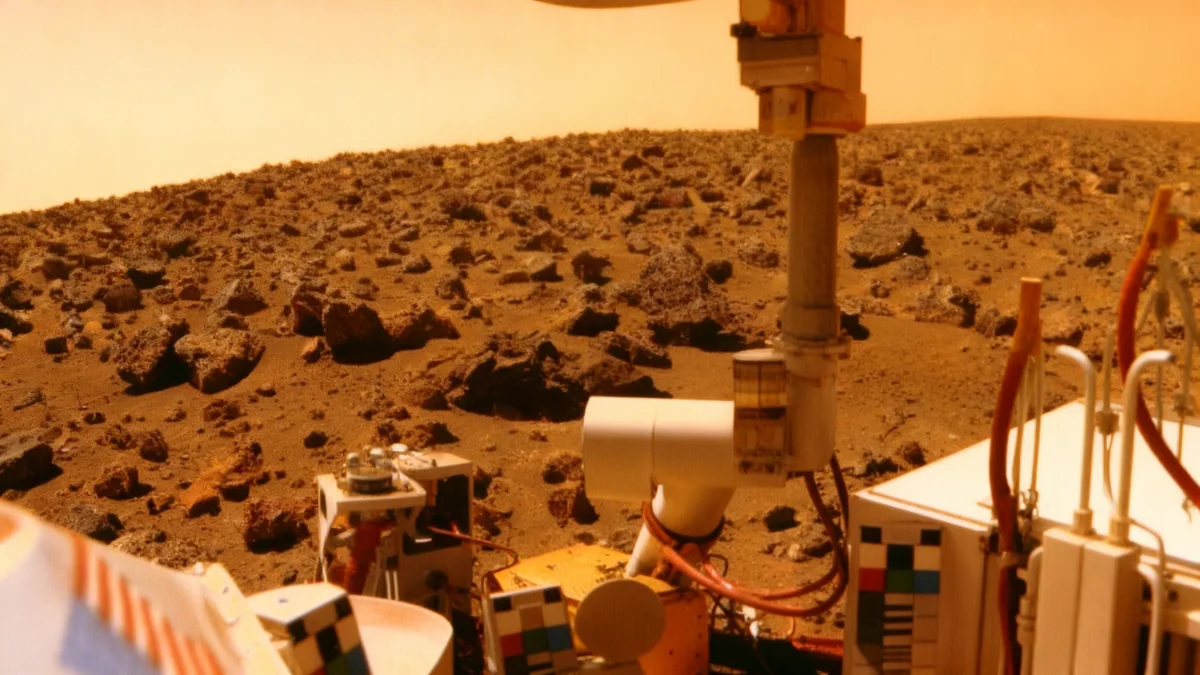

The study also modeled conditions on Mars. The results indicated that Mars likely formed with different oxygen levels, resulting in a mantle richer in phosphorus than Earth's but deficient in nitrogen, presenting a significant challenge for the development of life.

The Star-Planet Connection

Fortunately, the research offers a new, more targeted approach. Since planets form from the same disk of gas and dust as their host star, the chemical composition of a star can provide vital clues about the planets that orbit it.

By studying the chemistry of distant stars, scientists can infer whether their planetary systems had the right initial ingredients to produce a world like Earth. This could help prioritize which exoplanets are the most promising candidates for follow-up observations with powerful instruments like the James Webb Space Telescope.

"This makes searching for life on other planets a lot more specific," Walton explained. "We should look for solar systems with stars that resemble our own sun."

Ultimately, the study paints a picture of Earth as less of a cosmic certainty and more of a fortunate chemical accident. Our existence may hinge on a precise set of circumstances that most rocky worlds in the galaxy simply miss, making our planet a potentially rare and precious exception.