A team of scientists is challenging a nearly 50-year-old conclusion about life on Mars, proposing that NASA's Viking missions did, in fact, discover microbial life in 1976. They argue that the original data was misinterpreted due to a chemical compound that was unknown on the Martian surface at the time, a finding that could fundamentally alter our understanding of the Red Planet.

Key Takeaways

- In 1976, NASA's Viking landers conducted experiments that yielded positive signals for life on Mars.

- These results were dismissed because a separate instrument failed to detect organic molecules, a key component for life.

- A new analysis suggests the instrument did find organics, but they were destroyed during the heating process by a chemical called perchlorate.

- The discovery of perchlorate on Mars in 2008 is the key to reinterpreting the original Viking data.

- This new perspective suggests the decades-old conclusion that Mars is lifeless may have been a mistake.

The Viking Paradox of 1976

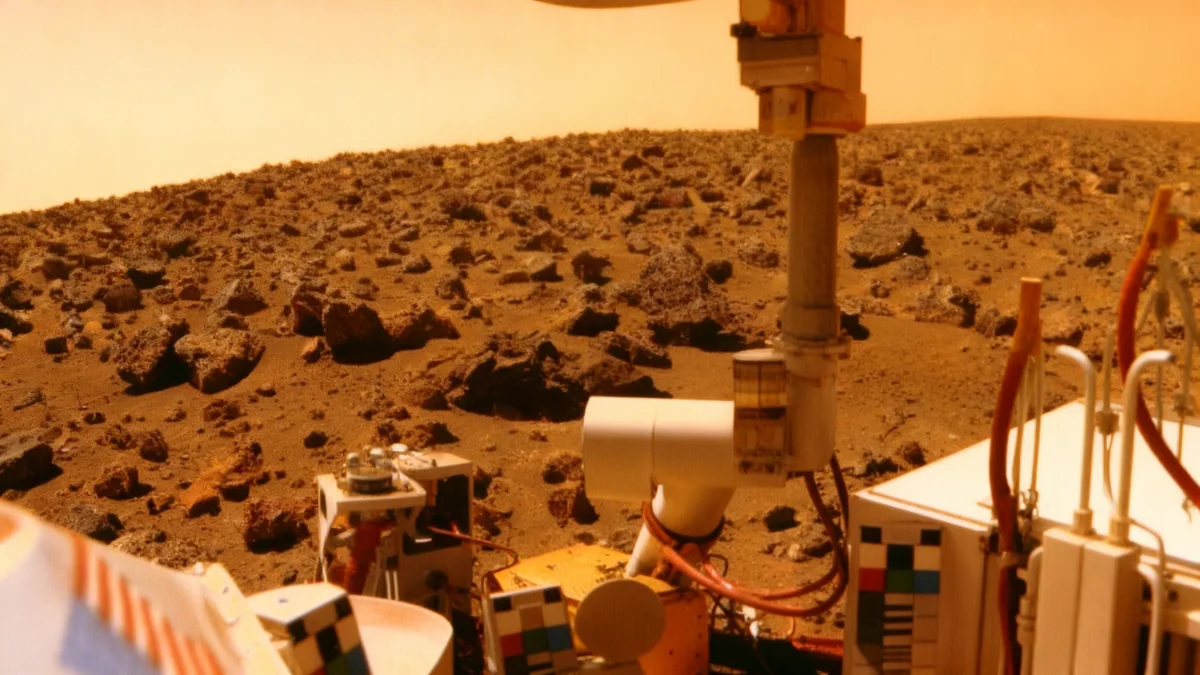

When NASA's twin Viking landers, Viking 1 and 2, touched down on Mars in 1976, they carried a suite of instruments designed to answer one of humanity's biggest questions: are we alone? Three of these experiments produced intriguing results, suggesting metabolic activity in the Martian soil—a potential sign of life.

However, another instrument, the Gas Chromatograph-Mass Spectrometer (GC-MS), reported no organic molecules. These molecules are the carbon-based building blocks of life as we know it. The absence of organics was a major contradiction. At the time, Viking Project Scientist Gerald Soffen famously concluded, "No bodies, no life."

The scientific consensus settled on the idea that a powerful, unknown oxidant in the Martian soil had both destroyed any organic matter and created false positives in the other life-detection experiments. The mission was officially declared to have found no evidence of life, a conclusion that has shaped Mars exploration for decades.

Dismissed Data Points

The original Viking team noted the GC-MS detected small amounts of methyl chloride and methylene chloride. These were dismissed as contaminants from cleaning solvents used on Earth. This assumption was a critical part of the argument against the presence of native Martian organics.

A Discovery Changes Everything

The story remained unchanged for over 30 years. Then, in 2008, NASA's Phoenix lander made a pivotal discovery: the Martian soil contained perchlorate, a type of salt that acts as an oxidant.

While perchlorate is an oxidant, it is not the super-reactive chemical the original Viking team theorized would be needed to explain the life-detection results. However, its presence provided a new lens through which to view the old data.

This discovery prompted new laboratory experiments on Earth. In 2010, astrobiologist Rafael Navarro-González demonstrated what happens when you heat organic material in the presence of perchlorate—the exact conditions of the Viking GC-MS experiment.

The Chemical Reaction

The experiment involved heating soil samples to vaporize any organic compounds for analysis. The Viking GC-MS first heated samples to 120°C (248°F) and then to 630°C (1,166°F). It was this high-temperature heating, combined with the newly discovered perchlorate, that researchers now believe is the key.

Revisiting the Viking Data

According to a new paper published in the journal Astrobiology by a team led by chemist Steve Benner, the 2010 experiments solve the Viking paradox. When Navarro-González heated organics with perchlorate, the reaction produced carbon dioxide and the same chlorinated methane compounds—methyl chloride—that Viking had dismissed as contamination.

"So now we know that the GC-MS didn't fail to discover organics — it did discover them, through their degradation products," Benner explained. The reaction produced approximately 99% carbon dioxide and 1% methyl chloride, which aligns with the unexpected burst of CO2 and trace amounts of chlorinated compounds seen in the 1976 data.

Benner's team argues that this means the original Viking instrument performed its job perfectly. It detected the burned remnants of Martian organic molecules. This removes the primary reason the original life-detection signals were invalidated.

A Model for Martian Life

With the evidence for organics now re-established, the positive signals from the other three experiments take on new significance. Benner and his colleagues propose a model for what Martian microbes might be like, which they call BARSOOM: Bacterial Autotrophs that Respire with Stored Oxygen On Mars.

This model suggests a lifeform that could explain the Viking findings:

- Photosynthesis: The microbes could generate their own food during the Martian day.

- Dormancy: They would become dormant during the cold Martian night.

- Oxygen Storage: They would store the oxygen produced during photosynthesis to use for respiration when they reawaken.

This cycle would account for the oxygen emission detected by Viking's Gas Exchange experiment, one of the original positive signals for life.

A 50-Year Setback?

The researchers contend that the initial misinterpretation of the Viking data effectively shut down a crucial scientific debate and set the search for life on Mars back by half a century. The official narrative that Mars was sterile became entrenched in scientific literature.

"The problem is that we now know that it did find organic molecules!" Benner stated, highlighting the disconnect between the old interpretation and modern knowledge. His team is now calling for the scientific community to reopen the discussion and rigorously re-examine the Viking evidence in light of new discoveries.

As the 50th anniversary of the Viking landings approaches, this new analysis poses a profound question: did we discover our first extraterrestrial neighbors decades ago and simply fail to recognize them?