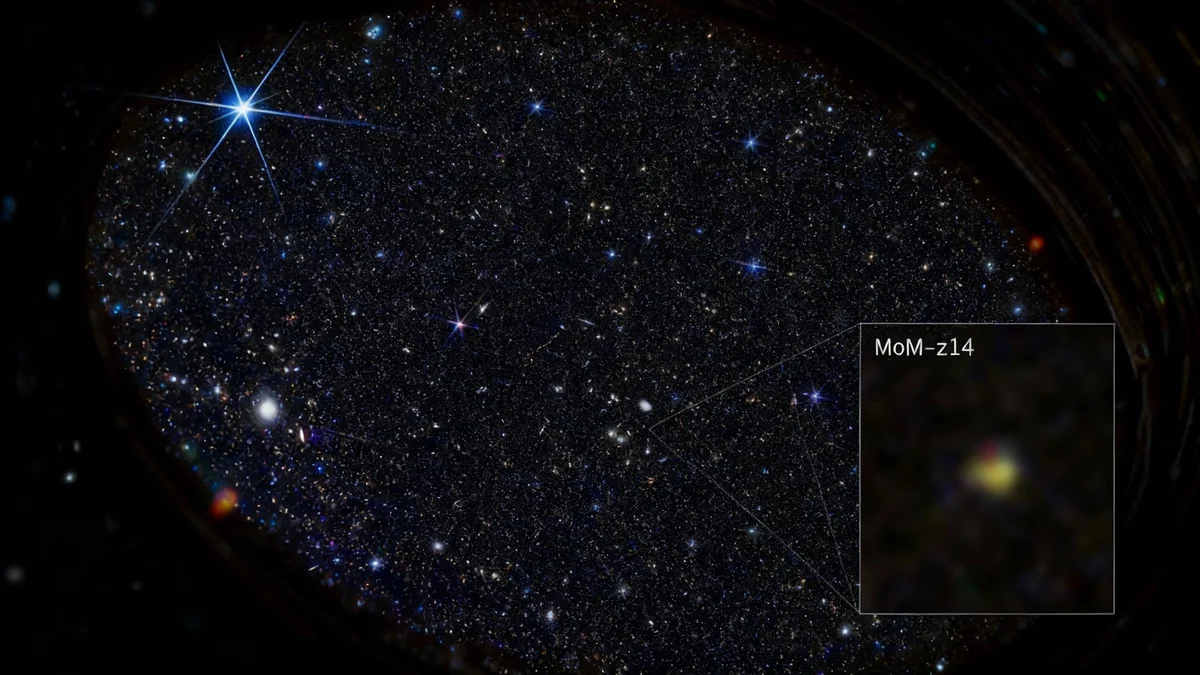

The James Webb Space Telescope has once again extended humanity's view into the deep past, confirming the existence of a galaxy that was shining just 280 million years after the Big Bang. This ancient stellar system, named MoM-z14, is not only one of the most distant objects ever observed but is also presenting new puzzles that challenge current models of the early universe.

By analyzing the light from MoM-z14, which has traveled for approximately 13.5 billion years to reach us, astronomers are gaining unprecedented insight into a period known as cosmic dawn. The findings suggest the first galaxies may have formed faster and shone brighter than previously believed, forcing a reevaluation of cosmic history.

Key Takeaways

- The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has spectroscopically confirmed galaxy MoM-z14 at a redshift of 14.44.

- This places the galaxy's existence at just 280 million years after the Big Bang, pushing the observational frontier closer to the universe's origin.

- MoM-z14 is unexpectedly bright, adding to a growing list of early galaxies that defy theoretical predictions.

- The galaxy shows unusual chemical signatures, such as high levels of nitrogen, which may point to the existence of a different class of stars in the early universe.

Pushing Back the Cosmic Frontier

Astronomers have confirmed that the light from galaxy MoM-z14 began its journey when the universe was in its infancy. Using the telescope's Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec), researchers measured a cosmological redshift of 14.44. This measurement is crucial for determining cosmic distances.

Redshift occurs because the universe is expanding. As light travels through this expanding space, its wavelength gets stretched, shifting it towards the red end of the spectrum. A higher redshift value means the object is farther away and existed earlier in time.

Understanding Redshift

In cosmology, redshift is a key tool. It not only tells us how far away an object is but also allows us to look back in time. Because light travels at a finite speed, observing a galaxy with a redshift of 14.44 is like looking at a snapshot of it as it appeared 13.5 billion years ago. The universe itself is estimated to be 13.8 billion years old.

Pascal Oesch, a co-principal investigator of the survey from the University of Geneva, emphasized the importance of this detailed confirmation. "We can estimate the distance of galaxies from images, but it’s really important to follow up and confirm with more detailed spectroscopy so that we know exactly what we are seeing, and when," he stated.

A Universe Brighter Than Expected

One of the most significant findings related to MoM-z14 is its surprising luminosity. This galaxy, along with several others discovered by Webb in the early universe, is far brighter than scientific models predicted. According to the research team, these early galaxies are appearing at a rate 100 times greater than theoretical studies anticipated before the telescope's launch.

This discrepancy is forcing scientists to rethink their understanding of star and galaxy formation in the primordial cosmos. "There is a growing chasm between theory and observation related to the early universe, which presents compelling questions to be explored going forward," said Jacob Shen, a postdoctoral researcher at MIT and a member of the team.

"With Webb, we are able to see farther than humans ever have before, and it looks nothing like what we predicted, which is both challenging and exciting."

This growing body of evidence suggests that the conditions in the early universe were more conducive to rapid, brilliant star formation than previously thought. The first stars may have been more massive and formed in denser clusters, leading to galaxies that shone with unexpected intensity.

Unusual Chemical Fingerprints

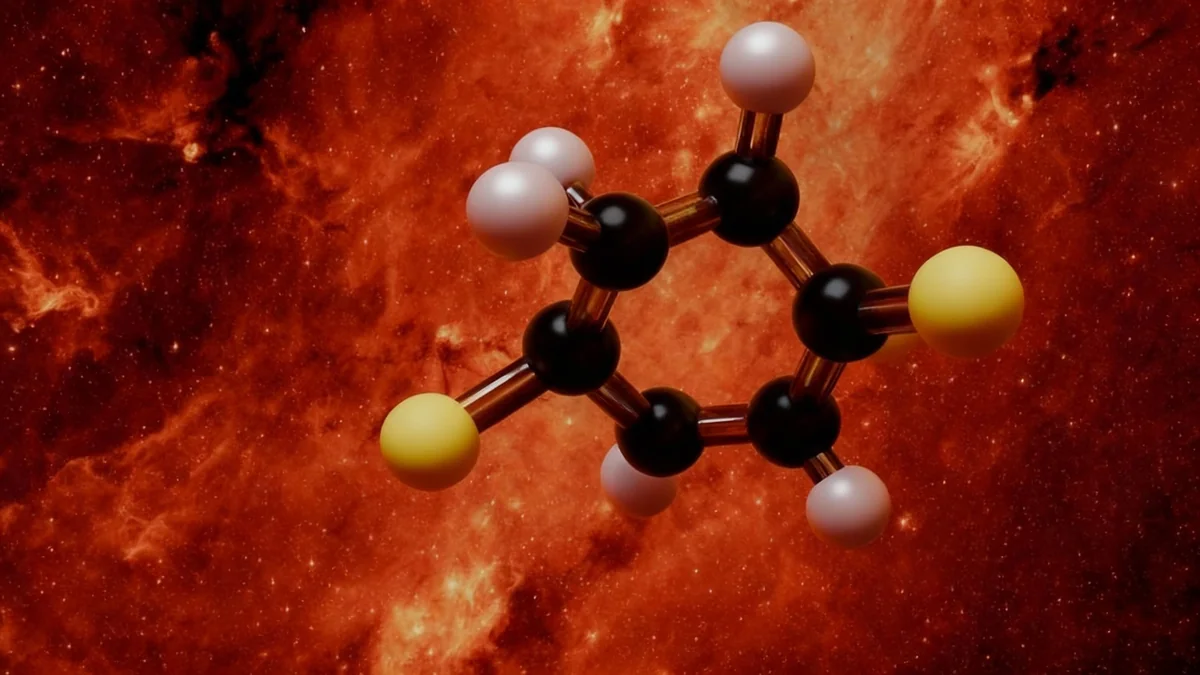

Beyond its brightness, MoM-z14 also displays a peculiar chemical composition. The galaxy shows a high abundance of nitrogen, an element that is typically produced over multiple generations of star life and death. Finding it in such quantities so early in cosmic history is a puzzle.

In the universe as we know it today, heavier elements like nitrogen are forged inside stars and scattered into space when they die. This material is then incorporated into new stars and planets. For a galaxy to be enriched with nitrogen just 280 million years after the Big Bang, this process would have had to happen remarkably fast.

The Nitrogen Puzzle

One theory proposed by the researchers is that the early universe hosted supermassive stars, a class of stars far larger than any seen today. These hypothetical giants could have lived fast, died young, and produced large amounts of nitrogen in a short period, explaining the signatures Webb is observing.

Interestingly, these chemical clues connect the most distant galaxies with some of the oldest stars in our own Milky Way. "We can take a page from archeology and look at these ancient stars in our own galaxy like fossils from the early universe," explained Rohan Naidu, the paper's lead author. He noted that some of these local, ancient stars also show similar nitrogen enrichment, creating a fascinating link between the cosmic dawn and our galactic neighborhood.

Lifting the Primordial Fog

The discovery of MoM-z14 also provides critical information about a key event in cosmic history: the Epoch of Reionization. For hundreds of millions of years after the Big Bang, the universe was filled with a dense, neutral hydrogen fog that made it opaque to certain types of light.

This cosmic dark age ended when the first stars and galaxies formed, emitting energetic light that ionized the surrounding hydrogen gas, clearing the fog and making the universe transparent. One of Webb's primary missions is to map out this process.

Observations of MoM-z14 show that it had already begun to carve out a bubble of clear, ionized space around itself. Each such discovery helps astronomers piece together the timeline of how and when the universe became the transparent cosmos we see today.

A Legacy of Discovery Continues

The James Webb Space Telescope was designed to answer these fundamental questions about our origins. Its ability to find these unexpectedly bright and chemically complex early galaxies confirms that the first few discoveries were not anomalies but part of a pattern.

Before Webb, the Hubble Space Telescope provided hints of this phenomenon with its discovery of GN-z11, a galaxy from 400 million years after the Big Bang. Webb has since confirmed that finding and pushed observations even further back in time.

The work is far from over. Scientists are looking forward to future observatories, like NASA's Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, which will be able to find thousands more of these distant objects. Yijia Li, a graduate student at Pennsylvania State University, noted the need for more data. "To figure out what is going on in the early universe, we really need more information... more galaxies to see where the common features are, which Roman will be able to provide," she said.

For now, each new image and spectrum from Webb adds another piece to the puzzle, revealing an early universe that was more dynamic and complex than ever imagined.