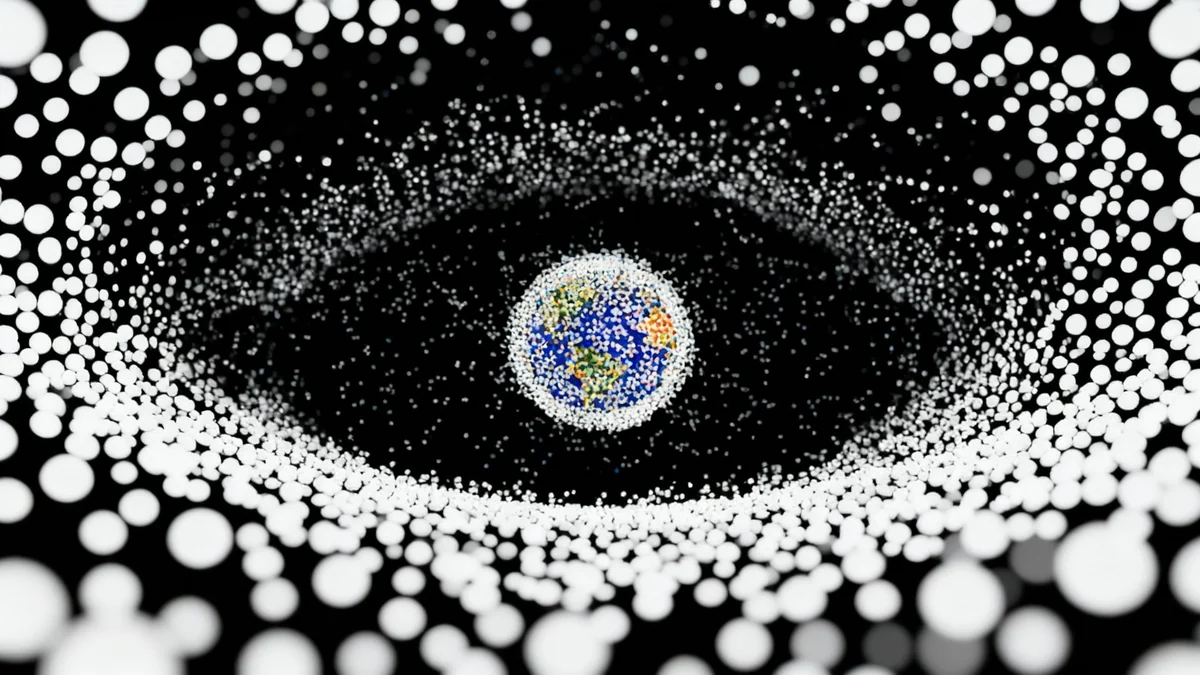

A vast and growing field of debris now encircles our planet, posing a significant threat to active satellites, space stations, and future missions. Researchers are now proposing a fundamental shift in how the space industry operates, moving from a disposable model to one centered on sustainability.

This new approach, detailed by researchers at the University of Surrey, advocates for a systemic change based on familiar principles: reduce, repair, and recycle. The goal is to prevent a catastrophic cascade of collisions that could render low Earth orbit unusable for generations.

Key Takeaways

- Over 10,000 tons of space debris, including more than 25,000 objects larger than four inches, currently orbit Earth.

- Researchers propose a new sustainable model for the space industry focused on reducing waste, repairing satellites, and recycling defunct hardware.

- The primary obstacle is the Kessler Syndrome, a theoretical scenario where collisions create a chain reaction of more debris.

- International law, such as the Outer Space Treaty, presents legal challenges as it designates all space objects as the permanent property of the launching nation.

The Crowded Skies Above

Low Earth orbit, the region of space within 1,200 miles of the surface, has become dangerously cluttered. Decades of space exploration have left a legacy of defunct satellites, spent rocket stages, lost tools, and even flecks of paint, all traveling at speeds exceeding 17,000 miles per hour.

Official catalogs track more than 25,000 pieces of debris larger than a softball. When smaller fragments are included, the number skyrockets to over 100 million. The total mass of this orbital junkyard is estimated to be more than 10,000 tons.

This is not a passive problem. The International Space Station frequently performs avoidance maneuvers to dodge tracked debris. Historical incidents highlight the very real danger posed by even small objects. During its first flight in 1983, the space shuttle Challenger's windshield was struck by a tiny piece of debris, leaving a bullet-like crack. The Hubble Space Telescope has also sustained damage, including a puncture through its antenna dish.

A High-Speed Threat

At orbital velocities, a collision with an object as small as a paint chip can cause significant damage to a satellite or spacecraft. The kinetic energy involved is immense, turning tiny fragments into powerful projectiles.

Two major satellite collisions, one in 2007 and another in 2009, dramatically worsened the situation. The debris generated from those two events alone now accounts for more than a third of all catalogued space junk, demonstrating how quickly the problem can escalate.

The Looming Threat of Kessler Syndrome

The greatest fear among space experts is a scenario known as the Kessler Syndrome. Proposed by NASA scientist Donald J. Kessler in 1978, it describes a tipping point where the density of objects in low Earth orbit becomes so high that collisions become inevitable.

Each collision would generate a cloud of new debris, which in turn increases the probability of further collisions. This could set off a chain reaction, a cascading series of impacts that would litter orbit with so much junk that it becomes impassable for satellites and future space missions.

The economic consequences would be severe. Our global economy relies heavily on satellite infrastructure for communication, navigation, weather forecasting, and financial transactions. A 2023 paper in the journal Space Policy estimated that if the space junk problem is not addressed, the resulting damage to satellite systems could reduce global GDP by as much as 1.95%.

"When you focus on individual technologies, you’ll miss the opportunities," said Jin Xuan, a researcher at the University of Surrey, emphasizing the need for a comprehensive strategy rather than isolated solutions.

A New Framework for Space Sustainability

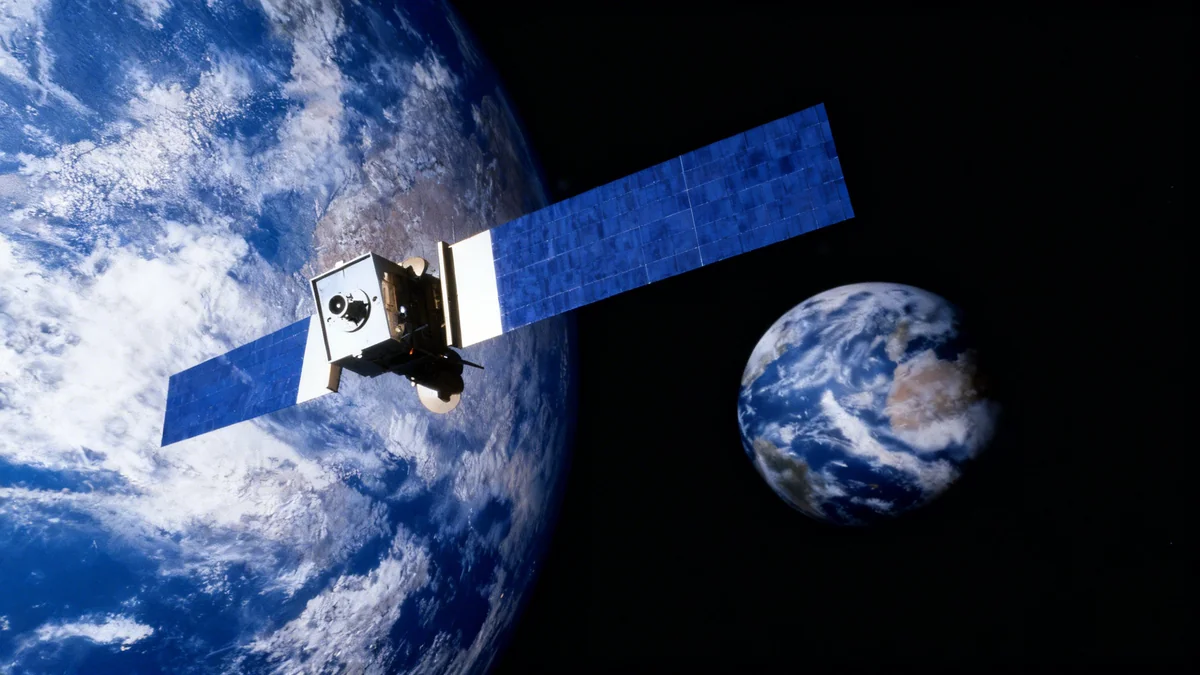

While some companies are developing innovative solutions—such as reusable rockets and robotic arms to capture dead satellites—experts argue these are only partial fixes. The new proposal from University of Surrey researchers calls for a complete paradigm shift, applying the principles of a circular economy to space operations.

The Three Pillars of a Sustainable Orbit

- Reduce: Design satellites and rockets with less material from the start. This includes creating satellites that can be refueled in orbit or are designed to de-orbit and burn up completely in the atmosphere at the end of their lifespan.

- Repair: Develop capabilities to service and repair existing satellites in orbit. This could involve repurposing space stations as orbital repair depots, extending the life of valuable assets and preventing them from becoming junk.

- Recycle: For objects that cannot be repaired, create systems to capture and recycle their materials in space. This would not only clean up orbit but also provide raw materials for future in-space manufacturing.

This "systems thinking" approach requires coordination across the entire industry, from design and manufacturing to launch and end-of-life management. "The space industry has been focused on safety and economic value, but sustainability hasn’t been a priority," Xuan noted. He believes the sector can learn valuable lessons from industries like chemical manufacturing, which have already integrated sustainability principles into their core operations.

The Legal and Political Hurdles

Cleaning up space is not just a technical challenge; it is also a complex legal and political one. The 1967 Outer Space Treaty, the foundational document of space law, complicates debris removal efforts.

One of its key provisions states that an object launched into space remains the property of the launching nation forever. This means one country cannot legally remove another country's debris without explicit permission. This rule was created to prevent nations from interfering with each other's active satellites, as a robotic arm designed to capture junk could just as easily be used to disable a military satellite.

"One of the potential troubles with any technology designed to recycle or to refurbish technologies in space, is that those very same technologies could be used as a weapon," explained Michael Dodge, a professor of space studies at the University of North Dakota.

However, another part of the treaty requires nations to avoid the harmful contamination of space, which could be interpreted as a mandate to clean up their own junk. Navigating these conflicting principles will be crucial for establishing an effective global framework for orbital debris management. For any large-scale recycling initiative to succeed, international cooperation and clear financial incentives will be essential.