A new study reveals that peptides, the fundamental components of proteins, can form spontaneously in the harsh conditions of interstellar space. This discovery, published in Nature Astronomy, challenges previous assumptions about the origins of life and suggests that the necessary ingredients could be widespread throughout the universe.

Researchers from Aarhus University successfully simulated the environment of deep space dust clouds in a laboratory setting, demonstrating a previously unknown pathway for the creation of complex organic molecules long before stars and planets are born.

Key Takeaways

- Scientists have shown that peptides, which form proteins, can be created in conditions mimicking interstellar space.

- The experiment involved irradiating the simple amino acid glycine at -260° C in a vacuum.

- This finding suggests that the essential building blocks for life are more common in the universe than previously believed.

- The research shifts the timeline for the formation of complex molecules, indicating they can exist before star formation.

Recreating the Cosmos in a Chamber

In a laboratory in Denmark, scientists have managed to replicate the extreme environment found in the vast, cold dust clouds that drift between stars. These interstellar nurseries, where new solar systems are born, were the focus of an experiment led by researchers Sergio Ioppolo and Alfred Thomas Hopkinson.

The team used a specialized ultra-high vacuum chamber to create conditions with almost no pressure. They then lowered the temperature to a frigid -260 degrees Celsius, mirroring the deep freeze of space.

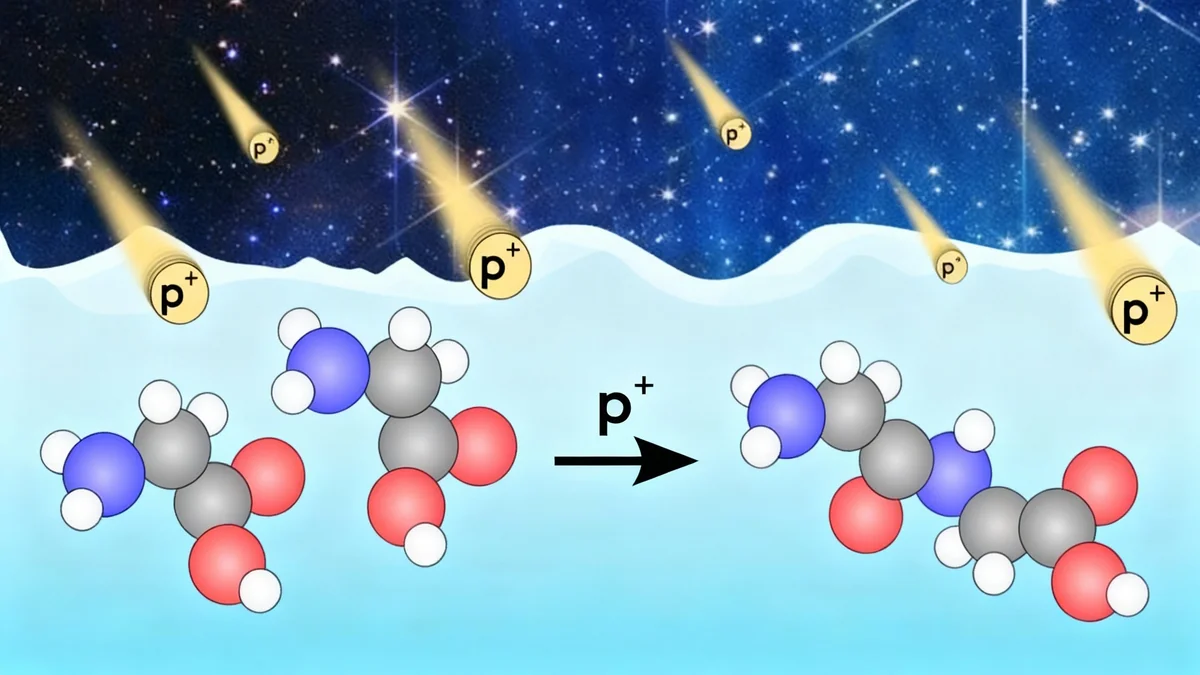

Inside this chamber, they placed a simple amino acid called glycine on a surface designed to act like an interstellar dust grain. The setup was then transported to a facility in Hungary, where it was bombarded with energy particles from an ion accelerator, simulating the effects of cosmic rays that permeate the galaxy.

Simulating Space

The experiment required maintaining an ultra-high vacuum and a temperature of just 13 Kelvin (approximately -260° C or -436° F) to accurately mimic the conditions inside a dense interstellar cloud.

An Unexpected Chemical Reaction

The results of the experiment were significant. When analyzing the material after irradiation, the scientists found that the individual glycine molecules had linked together to form peptides. Peptides are short chains of amino acids, and when these chains link together, they create proteins—the complex molecules essential for all known life.

"We saw that the glycine molecules started reacting with each other to form peptides and water," said Alfred Thomas Hopkinson, a postdoctoral researcher involved in the study. "This indicates that the same process occurs in interstellar space."

This process demonstrates a direct, non-water-based pathway for peptide formation. It suggests that these crucial molecules can be created on the surfaces of dust grains that will eventually clump together to form asteroids, comets, and planets.

A New Timeline for Life's Origins

The discovery fundamentally alters the scientific understanding of when and where the building blocks of life can form. Previously, it was widely believed that only simple molecules could exist in the diffuse gas of interstellar clouds. The prevailing theory was that more complex structures like peptides could only form much later, within the dense, warmer protoplanetary disks surrounding young stars.

"We used to think that only very simple molecules could be created in these clouds," explained Associate Professor Sergio Ioppolo. "But we have shown that this is clearly not the case."

From Dust Clouds to Planets

Interstellar clouds are massive collections of gas and dust. Over millions of years, gravity causes these clouds to collapse, forming dense cores that ignite into stars. The leftover material flattens into a disk, where planets, moons, and asteroids eventually take shape. This new research suggests these materials are already seeded with complex organic molecules.

This finding implies that the raw materials for life are not just present but are actively being assembled long before planets even exist. When these dust grains are incorporated into newly forming celestial bodies, they deliver these prebiotic molecules, potentially jump-starting the chemical processes that could lead to life on habitable worlds.

Implications for Extraterrestrial Life

The research significantly boosts the statistical probability of life emerging elsewhere in the cosmos. If the fundamental components of proteins are being created naturally and abundantly throughout the galaxy, then the chances of them landing on a rocky planet in a star's habitable zone increase dramatically.

"Eventually, these gas clouds collapse into stars and planets," Ioppolo noted. "Bit by bit, these tiny building blocks land on rocky planets... If those planets happen to be in the habitable zone, then there is a real probability that life might emerge."

A Universal Chemical Process

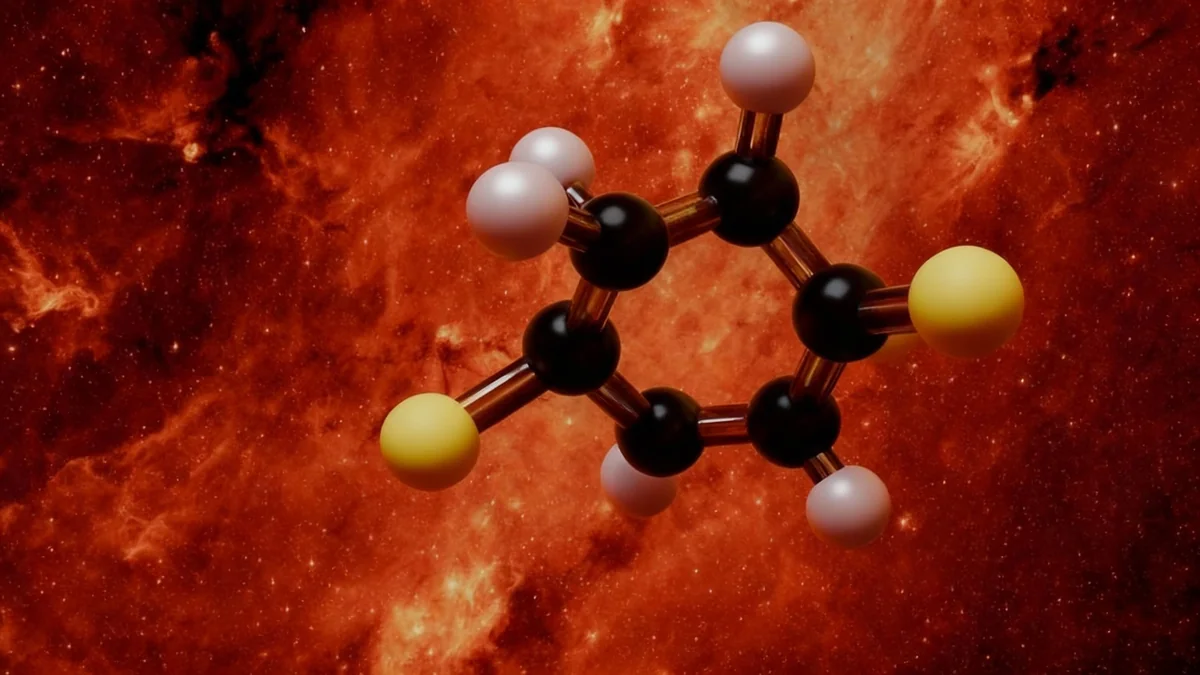

The chemical reaction that binds amino acids into peptides is universal. While the experiment focused on glycine, the simplest amino acid, the researchers believe the same process would apply to more complex amino acids as well.

- Universal Reaction: All types of amino acids bond into peptides through the same fundamental chemical process.

- Likely Abundance: This suggests that a wide variety of peptides are likely forming in interstellar space.

- Future Research: The team plans to investigate whether other essential molecules for life, such as nucleobases and membranes, can also form under these conditions.

Professor Liv Hornekær, who leads the Center for Interstellar Catalysis where the research was conducted, emphasized the potential role of these molecules. "They might actively participate in early prebiotic chemistry, catalyzing further reactions that lead toward life."

While the exact origin of life on Earth remains a mystery, this research provides a compelling piece of the puzzle. It shows that the universe is a vast chemical laboratory, capable of producing the complex ingredients for life long before they are needed.

"We've already discovered that many of the building blocks of life are formed out there, and we'll likely find more in the future," Ioppolo concluded.