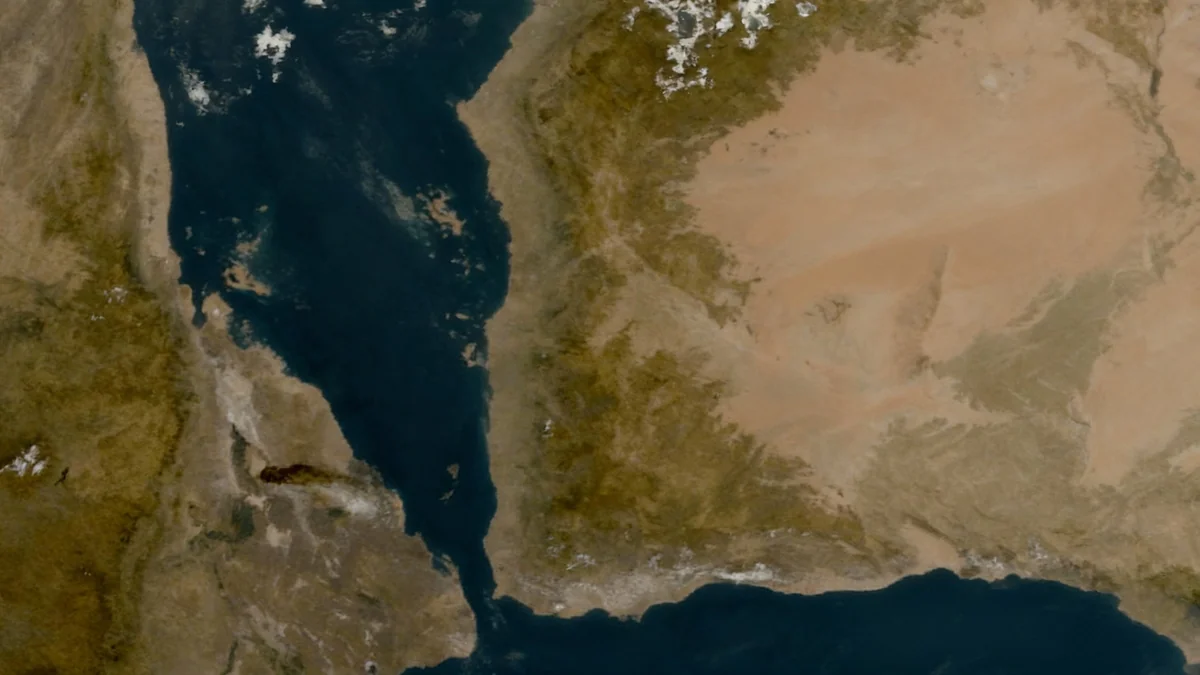

In a landmark experiment at CERN, scientists have confirmed that antimatter responds to gravity just like normal matter, falling downwards rather than up. The findings from the ALPHA-g experiment provide the strongest evidence yet that Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity applies to the mysterious counterpart of matter, settling a long-standing question in fundamental physics.

The result, while anticipated by many physicists, closes a significant loophole in our understanding of the universe. Had antimatter been repelled by gravity, it would have required a complete overhaul of modern physics.

Key Takeaways

- An experiment at CERN, known as ALPHA-g, directly observed the effect of gravity on antimatter for the first time.

- The results show that antihydrogen atoms fall downwards, consistent with the behavior of regular matter.

- This outcome supports Einstein's weak equivalence principle, a cornerstone of his theory of general relativity.

- Approximately 80% of the observed antiatoms fell through the bottom of the experimental trap, confirming the downward motion.

- While the direction of the fall is confirmed, future research will focus on whether the rate of fall is identical to that of matter.

A Foundational Question Answered

For decades, one of the most intriguing questions in physics has been how antimatter interacts with gravity. While theories predicted it should behave identically to matter, no one had ever directly observed it. The technical challenges of creating and containing antimatter, which annihilates on contact with regular matter, made such an experiment incredibly difficult.

At the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN), the ALPHA (Antihydrogen Laser Physics Apparatus) collaboration developed a sophisticated setup to finally put the question to the test. The experiment, named ALPHA-g, was designed to measure gravity's pull on this elusive substance.

The result provides a crucial piece of the puzzle. It reinforces the idea that the laws of gravity are universal, applying to all forms of mass and energy in the same way. This confirmation is a significant victory for Einstein's century-old theory.

What Is the Weak Equivalence Principle?

The weak equivalence principle is a key concept in Einstein's theory of general relativity. It states that the trajectory of a falling object is independent of its internal structure or composition. In simpler terms, in a vacuum, a feather and a hammer will fall at the exact same rate. This was famously demonstrated by astronaut David Scott on the Moon during the Apollo 15 mission in 1971. The ALPHA-g experiment extended this principle to one of the most exotic substances known to exist.

The Intricate Science of Falling Anti-Atoms

To achieve this result, researchers had to overcome immense technical hurdles. The first step was to create antihydrogen, the simplest form of an anti-atom. This was done by taking antiprotons and combining them with positrons (the antimatter equivalent of electrons).

Because these antihydrogen atoms are electrically neutral, they are not easily manipulated by electric fields. Instead, the team used a device called a Penning trap, which uses powerful magnetic fields to contain the anti-atoms. This magnetic bottle holds the anti-atoms in place, preventing them from touching the walls of the container and annihilating.

A Chilling Experiment: To minimize random movements, the trapped antihydrogen atoms were cooled to a temperature near absolute zero, just half a degree above -273.15°C (-459.67°F).

Once a small cloud of about 100 anti-atoms was trapped and cooled, the moment of truth arrived. The scientists slowly weakened the magnetic fields at the top and bottom of the trap. This allowed the anti-atoms to escape. The researchers then watched to see where they would go.

As each anti-atom escaped and hit the wall of the trap, it annihilated, producing a tiny flash of light. By detecting these flashes, the team could determine whether the anti-atoms had drifted up or fallen down. After carefully analyzing the data and filtering out interference from cosmic rays, the conclusion was clear: roughly 80% of the annihilations occurred below the trap's center, indicating the anti-atoms were pulled downward by Earth's gravity.

From Mathematical Quirks to Experimental Reality

The concept of antimatter originated not in a laboratory but in the pages of a notebook. In the 1920s, physicist Paul Dirac was attempting to merge quantum mechanics with special relativity. His resulting equation had two solutions: one for a particle with positive energy, and another for a particle with negative energy.

Dirac's solution was to propose a "sea" of negative energy particles filling the vacuum of space. When energy was added, a particle could be kicked into the positive realm, leaving behind a "hole." This hole would behave just like a particle but with an opposite charge. This was the first prediction of antimatter, purely from mathematics.

This theoretical curiosity was confirmed just a few years later with the discovery of the positron. Since then, antimatter has become a critical tool for physicists exploring the fundamental nature of the universe. Because it is a pure product of the quantum world, it serves as a perfect probe for testing the limits of general relativity, our theory of gravity.

The two theories, quantum mechanics and general relativity, are famously incompatible. Finding a bridge between them is one of the biggest goals in modern physics. Testing antimatter's response to gravity was seen as a potential pathway to discovering new physics that could unite these two pillars of science.

The Quest Is Not Over

While the ALPHA-g experiment has answered a major question, it has opened the door to more precise inquiries. The current results confirm that antimatter falls down, but they are not yet precise enough to determine if it falls at the exact same rate as normal matter.

Future experiments will aim to measure the acceleration of antihydrogen with much greater accuracy. Even a tiny deviation, perhaps a 1% difference compared to regular matter, would be a revolutionary discovery. Such a finding would violate the weak equivalence principle and signal the existence of new forces or dimensions beyond our current understanding.

For now, however, Einstein's framework remains robust. The universe, it seems, treats matter and its mirror image with gravitational impartiality. Whether you drop a hammer, a feather, or a particle of antihydrogen, they all fall toward the ground.