A volcano in northern Ethiopia, considered dormant for at least 12,000 years, erupted unexpectedly on Sunday, November 23. The event sent a colossal ash plume thousands of feet into the atmosphere, which has since traveled across Asia.

The eruption of Hayli Gubbi, located in the remote Afar region, marks its first recorded activity in the Holocene epoch, the geological period that began after the last ice age. The explosive phase of the eruption lasted for several hours, catching local communities and international observers by surprise.

Key Takeaways

- The Hayli Gubbi volcano in Ethiopia erupted on November 23 for the first time in at least 12,000 years.

- An ash cloud from the eruption reached an altitude of 45,000 feet (13,700 meters).

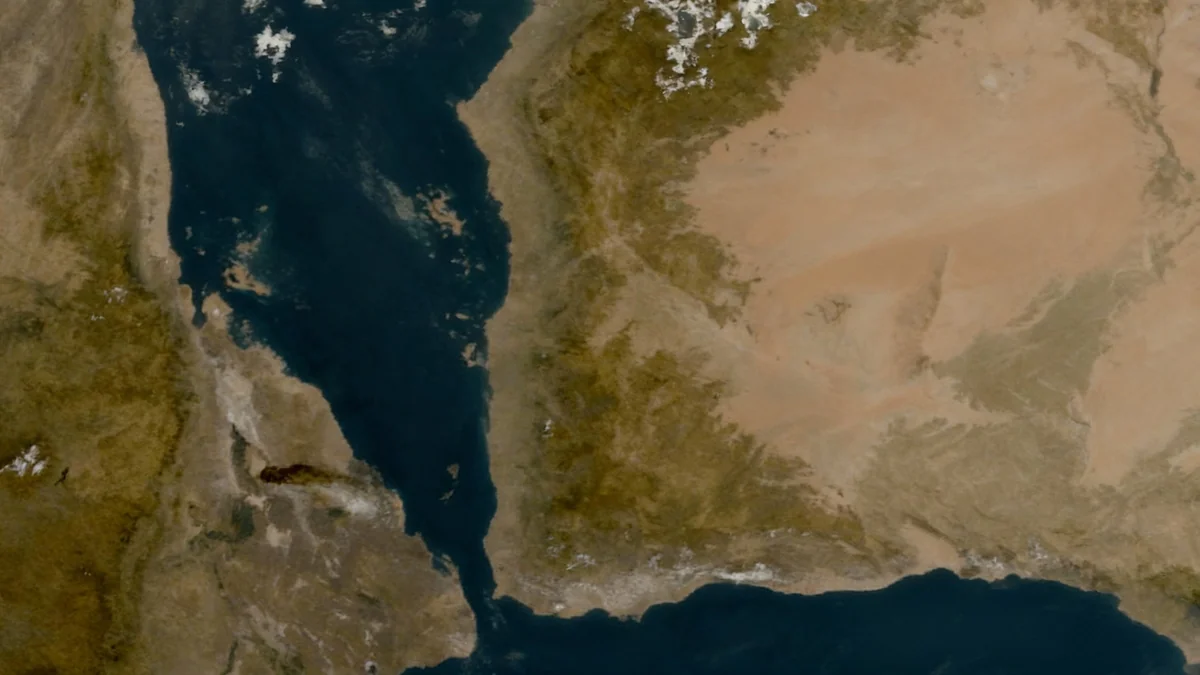

- The plume of ash and sulfur dioxide has spread northeast across the Red Sea, reaching as far as India and China.

- While no casualties have been reported, falling ash has impacted local villages and grazing land for livestock.

A Sudden Awakening

The eruption began around 8:30 a.m. UTC on Sunday. Residents in the nearby village of Afdera described the event's suddenness and force. Ahmed Abdela, a local resident, told the Associated Press that the eruption "felt like a sudden bomb had been thrown with smoke and ash."

By evening, the Toulouse Volcanic Ash Advisory Center (VAAC) in France reported that the explosive phase had ceased. The center, which uses satellite data to monitor atmospheric hazards, tracked the plume as it moved away from the African continent.

Hayli Gubbi is the southernmost volcano in the Erta Ale Range, a geologically active area. This mountain chain is part of the East African Rift System, a major tectonic boundary where the African continent is slowly splitting apart.

Geological Context: The East African Rift

The Afar region is a geological hotspot where three tectonic plates are diverging. This constant stretching and thinning of the Earth's crust creates pathways for magma to reach the surface, resulting in significant volcanic activity. While Hayli Gubbi has been silent for millennia, another volcano in the same range, Erta Ale, has been in a state of continuous eruption since at least 1967.

Global Reach of the Ash Plume

Satellite imagery captured the dramatic scale of the eruption. The initial plume of ash and gas rose to an estimated height of 45,000 feet, or nearly 14 kilometers, entering the stratosphere where it could be carried by high-altitude winds.

The cloud first drifted northeast over Yemen and Oman. Within a day, it had traveled across northern India and was detected over parts of China. Monitoring responsibility was transferred from the Toulouse VAAC to its counterpart in Tokyo as the plume moved eastward.

The Copernicus Sentinel-5P satellite, operated by the European Union, detected a significant release of sulfur dioxide, a common volcanic gas that can impact air quality and climate.

While the immediate explosive danger has passed, the dispersal of such a large ash cloud is a major concern for aviation and can have short-term effects on regional weather patterns.

Impact on Local Communities

Initial reports indicate that no human lives or livestock were lost in the eruption. However, the aftermath presents serious challenges for the region's inhabitants, who are primarily pastoralists.

Mohammed Seid, a local administrator, expressed concern over the environmental impact. He informed the Associated Press, "While no human lives and livestock have been lost so far, many villages have been covered in ash and as a result their animals have little to eat." The fine volcanic ash can contaminate water sources and cover grazing lands, threatening the livelihood of local communities.

A Reminder of Dormant Power

The reawakening of Hayli Gubbi serves as a powerful reminder that even volcanoes considered extinct can become active. A volcano is typically classified as extinct if it has not erupted during the Holocene, which began approximately 11,700 years ago. However, the region where Hayli Gubbi is located is not extensively studied, meaning past eruptions may have gone unrecorded.

Volcanologists note that as long as an underground magma source exists, the potential for an eruption remains, even after thousands of years of inactivity.

"So long as there are still the conditions for magma to form, a volcano can still have an eruption even if it hasn’t had one in 1,000 years, 10,000 years," Arianna Soldati, a volcanologist at North Carolina State University, told Scientific American.

The event underscores the dynamic and unpredictable nature of Earth's geology, especially in tectonically active zones like the East African Rift.