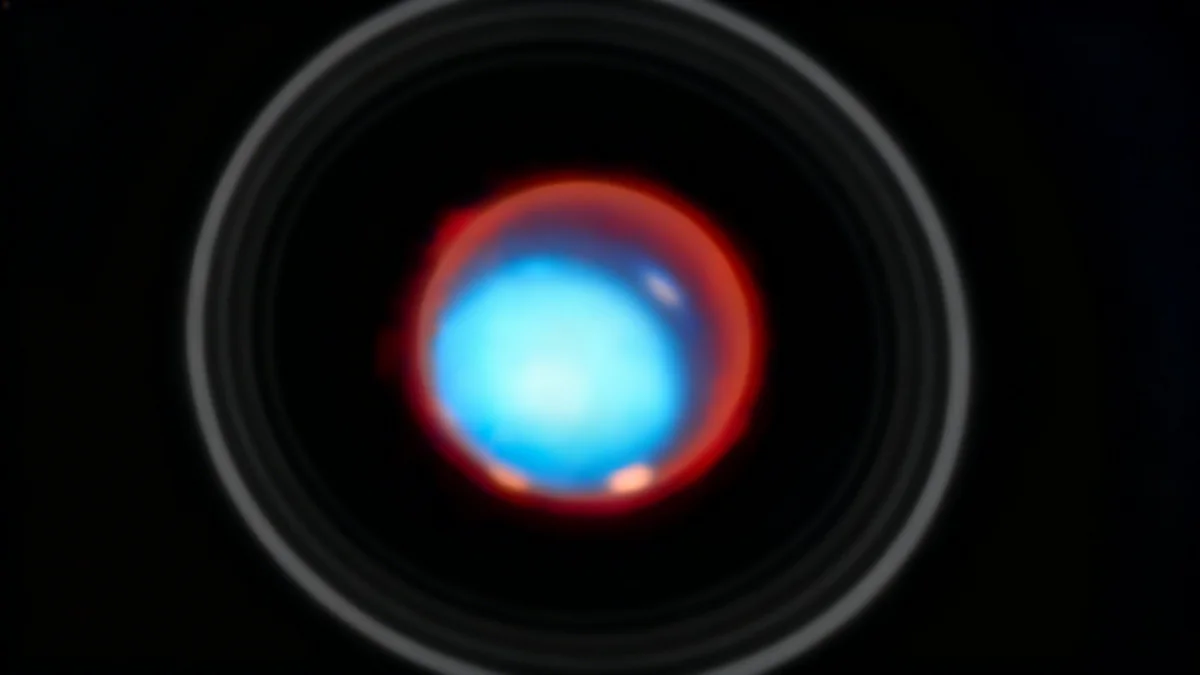

New research indicates that Ariel, one of Uranus's icy moons, may have once concealed a vast ocean of liquid water beneath its frozen surface. The study, which modeled the moon's past orbital behavior, suggests that gravitational forces from Uranus could have generated enough heat to maintain this hidden ocean, adding to evidence that the Uranian system was once home to multiple ocean worlds.

The findings provide a compelling explanation for the moon's unusually complex and fractured terrain, which has long puzzled planetary scientists. This discovery strengthens the scientific case for a dedicated mission to explore Uranus and its satellites in greater detail.

Key Takeaways

- A new study suggests Uranus's moon Ariel once had a subsurface ocean over 100 miles deep.

- The moon's fractured surface is likely the result of tidal heating from a highly eccentric past orbit.

- This research, combined with similar findings for the moon Miranda, suggests Uranus may have hosted multiple ocean worlds.

- The study reinforces calls for a NASA flagship mission to the Uranus system to confirm these findings.

Geological Clues on an Icy Surface

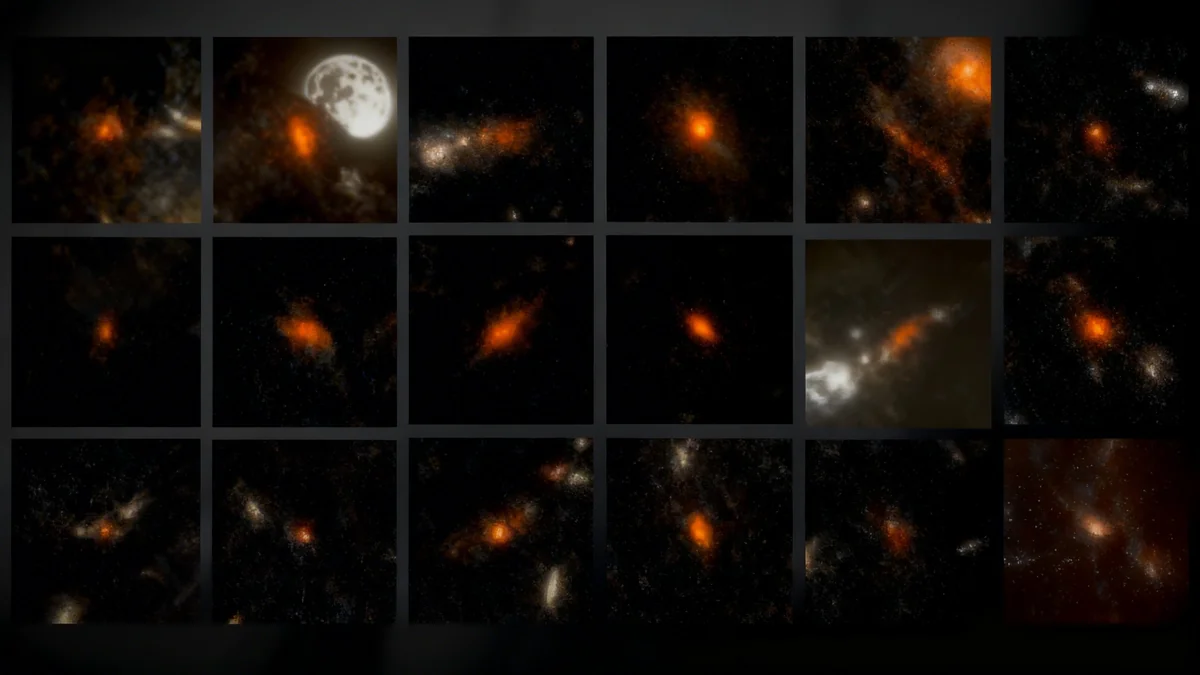

Ariel, the second-closest of Uranus's major moons, displays a surface that is both exceptionally bright and geologically complex. Measuring approximately 720 miles (1,159 kilometers) in diameter, its landscape is a mix of ancient, heavily cratered terrain alongside much younger, smoother plains. These features suggest a history of significant geological activity.

Researchers have long been interested in the large cracks and ridges that crisscross Ariel's surface. These formations are indicative of cryovolcanism, a process where icy materials erupt instead of molten rock. According to a new study led by Caleb Strom of the University of North Dakota, such large-scale features would be difficult to explain without the presence of a liquid layer beneath the moon's ice shell.

What is Cryovolcanism?

Cryovolcanism, or ice volcanism, is a phenomenon observed on icy moons and other celestial bodies in the outer solar system. Instead of silicate magma, these "volcanoes" erupt volatiles such as water, ammonia, or methane, which are often mixed with solid materials. This process can reshape a moon's surface, creating smooth plains and complex fracture systems.

Alex Patthoff, a senior scientist at the Planetary Science Institute and a co-author of the study, highlighted the moon's distinct characteristics. "Ariel is pretty unique in terms of icy moons," Patthoff stated, emphasizing the need to understand the forces that shaped it.

The Role of a Wobbling Orbit

To understand the source of Ariel's geological activity, the research team modeled its interior structure and past orbital dynamics. Their focus was on its orbital eccentricity, which measures how much an orbit deviates from a perfect circle. A more eccentric orbit leads to greater variations in the gravitational pull from its parent planet.

The models concluded that Ariel's orbit once had an eccentricity of about 0.04. While this number seems small, it is roughly 40 times greater than its current, nearly circular orbit. This past eccentricity would have been four times more pronounced than that of Europa, Jupiter's famously active icy moon.

Gravitational Squeezing and Heating

The constant stretching and squeezing from Uranus's gravity, a process known as tidal heating, would have generated significant friction and heat within Ariel's interior. This energy could have been sufficient to melt ice and maintain a liquid water ocean beneath the crust.

The researchers determined that the sheer scale of the fractures and ridges seen on Ariel's surface could only be explained by an ice crust flexing over a liquid layer. This scenario points to two main possibilities: either Ariel had a massive ocean under a relatively thin ice shell, or a smaller ocean that experienced stronger tidal stresses from its orbit.

"But either way, we need an ocean to be able to create the fractures that we are seeing on Ariel's surface," Patthoff explained in a statement.

A System of Potential Ocean Worlds

This new research on Ariel builds upon previous work by the same team. A 2024 study provided similar evidence for a past subsurface ocean on Miranda, another of Uranus's inner moons. Taken together, these findings paint a picture of a system that may have been rich in liquid water.

Tom Nordheim of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, who is the principal investigator for the research, noted the broader implications.

"We are finding evidence that the Uranus system may harbor twin ocean worlds," Nordheim said.

The presence of subsurface oceans is a primary focus in astrobiology, the study of the potential for life beyond Earth. Liquid water is a fundamental requirement for life as we know it. Hidden oceans, protected from harsh surface conditions by thick ice shells, are considered prime candidates for hosting extraterrestrial habitats. The energy needed to sustain such an environment could come from tidal heating or the decay of radioactive elements in the moon's core.

While scientists do not yet know when Ariel's ocean may have formed or how long it lasted, the study provides a critical framework for understanding how such oceans can evolve in the cold, distant reaches of the outer solar system.

Strengthening the Case for a Uranus Mission

The findings from this study add significant weight to the growing calls for a dedicated robotic mission to Uranus. The planet has only been visited once, a brief flyby by the Voyager 2 spacecraft in 1986. Consequently, much about the ice giant and its 27 moons remains a mystery.

The scientific community has prioritized such an expedition. The National Academies' decadal survey, which outlines NASA's top priorities, recommended the Uranus Orbiter and Probe as the highest-priority flagship mission to begin in the 2023–2032 timeframe. This proposed mission would involve an orbiter studying the planet, its rings, and its moons for several years, as well as a probe that would descend into its atmosphere.

A mission of this type could provide definitive answers about the potential oceans on Ariel and Miranda. Currently, spacecraft have only imaged the southern hemispheres of these moons. The models developed by Strom's team can help predict what a future mission might find in the unexplored northern regions.

Scientists believe a long-term Uranus mission could be as transformative as the Cassini mission was for Saturn. Cassini revolutionized our understanding of the ringed planet, discovering methane lakes on its moon Titan and a subsurface ocean on Enceladus. A similar exploration of Uranus could unlock secrets about its extreme axial tilt, its dense ring system, and the history of its potentially life-bearing moons.

As Nordheim concluded, computer models can only take us so far. "Ultimately, we just need to go back to the Uranus system and see for ourselves."