As humanity sets its sights on returning to the Moon and venturing to Mars, scientists are confronting a fundamental challenge: the human body is not designed for deep space. Beyond the protective bubble of Earth's magnetosphere, astronauts face a barrage of cosmic radiation and the relentless effects of microgravity, posing significant risks to their health on long-duration missions.

Researchers are now in a race to understand these dangers and develop innovative countermeasures. From advanced shielding and preventative medicines to miniature organ models sent into space, the effort to protect future explorers is pushing the boundaries of biology and technology, with potential benefits for medicine back on Earth.

Key Takeaways

- Long-duration missions to the Moon and Mars expose astronauts to severe health risks, including galactic cosmic radiation and microgravity effects.

- Every physiological system, from bones and muscles to the cardiovascular system, is negatively impacted by extended time in space.

- Scientists are developing countermeasures like hydrogen-based shielding, specialized drugs, and even gut bacteria engineered to produce protective compounds.

- Advanced research models, such as organs-on-a-chip, are being developed to test the effects of deep space on human cells without risking astronauts' lives.

- Discoveries made in space medicine could lead to new treatments for age-related diseases, cancer, and neurodegenerative conditions on Earth.

The Unseen Dangers of Deep Space

For more than two decades, humans have maintained a continuous presence in low-Earth orbit aboard the International Space Station (ISS). This has provided a wealth of data on how the body adapts to space, but it's an incomplete picture. The ISS, orbiting just 250 miles above Earth, is still largely shielded by our planet's magnetic field.

Missions to the Moon and Mars will take humans far beyond this protective shield, into an environment dominated by galactic cosmic radiation (GCR). These are high-energy particles from distant cosmic events that can penetrate conventional shielding and damage human cells.

"We don't know how a human being will do in that environment," said Dorit Donoviel, executive director of the Translational Research Institute for Space Medicine (TRISH) at Baylor College of Medicine. "We are essentially sending people on a mission to Mars... and don't really, really know for sure how they're going to react."

Radiation's Toll on the Body

On Earth, particle accelerator experiments simulating GCR have shown worrying results in animal models. These studies linked exposure to increased kidney dysfunction, accelerated cancer development, and significant cognitive impairments.

Beyond radiation, the absence of gravity takes a toll. "Every physiological system within the human body is impacted by space," explained Fathi Karouia, a space life scientist at the Blue Marble Space Institute of Science and NASA Ames Research Center. Without the constant pull of gravity, bones lose density, muscles atrophy, and the cardiovascular system weakens.

A Race for Protection: Shielding and Medicine

Protecting astronauts requires a multi-layered approach, as no single solution is sufficient. The first line of defense is shielding, but GCR presents a unique problem. Heavy ions can strike materials like lead and create a spray of secondary, equally dangerous particles.

Researchers believe the most effective shielding materials are those rich in hydrogen, such as water or specialized plastics and carbon fiber composites. Hydrogen's light nucleus is better at absorbing energy from GCR particles without creating secondary radiation.

Even with the best shielding, some radiation will always get through. This has led to a major push for pharmaceutical countermeasures—drugs that could protect or repair cells from radiation damage.

"If you're giving a drug to a healthy human being to prevent a disease... it's got to be super safe. That raises the bar really high on what you would give as a radiation mitigator."

<

The challenges are immense. A drug must be highly effective with minimal side effects. It also needs to be stable enough to survive a multi-year journey to Mars while being exposed to the same radiation it is meant to protect against.

The Logistics of Space Medicine

The sheer volume of medication required for a multi-year Mars mission presents a logistical hurdle. Every ounce of mass on a spacecraft is carefully calculated. As Donoviel explained, mission planners must weigh the value of bringing medication against essentials like food, water, and fuel. This constraint is driving innovation toward more efficient solutions.

One of the most forward-thinking ideas involves using the human body as its own pharmacy. TRISH is funding research into creating a "bespoke cocktail of microbes" that would live in an astronaut's gut. These engineered bacteria could continuously produce protective nutritional compounds, eliminating the need for bulky pill supplies.

Testing Without Humans: The Future of Research

Before any new drug or countermeasure can be approved for astronauts, it must undergo rigorous testing. However, sending humans into deep space just to test a theory is not an option. This is where cutting-edge biological models come into play.

Masafumi Muratani, a molecular biologist at the University of Tsukuba, is pioneering the use of induced pluripotent stem cells. His team plans to take cells from astronauts, revert them to stem cells, and then grow them into specific tissues to be exposed to simulated space environments on Earth.

"We can potentially assess how an individual astronaut will react in a real space mission before the mission, using the cell model as a surrogate of the reaction of the human."

This approach could allow for personalized risk assessments, identifying which astronauts might be more susceptible to certain space-related health issues and tailoring countermeasures accordingly.

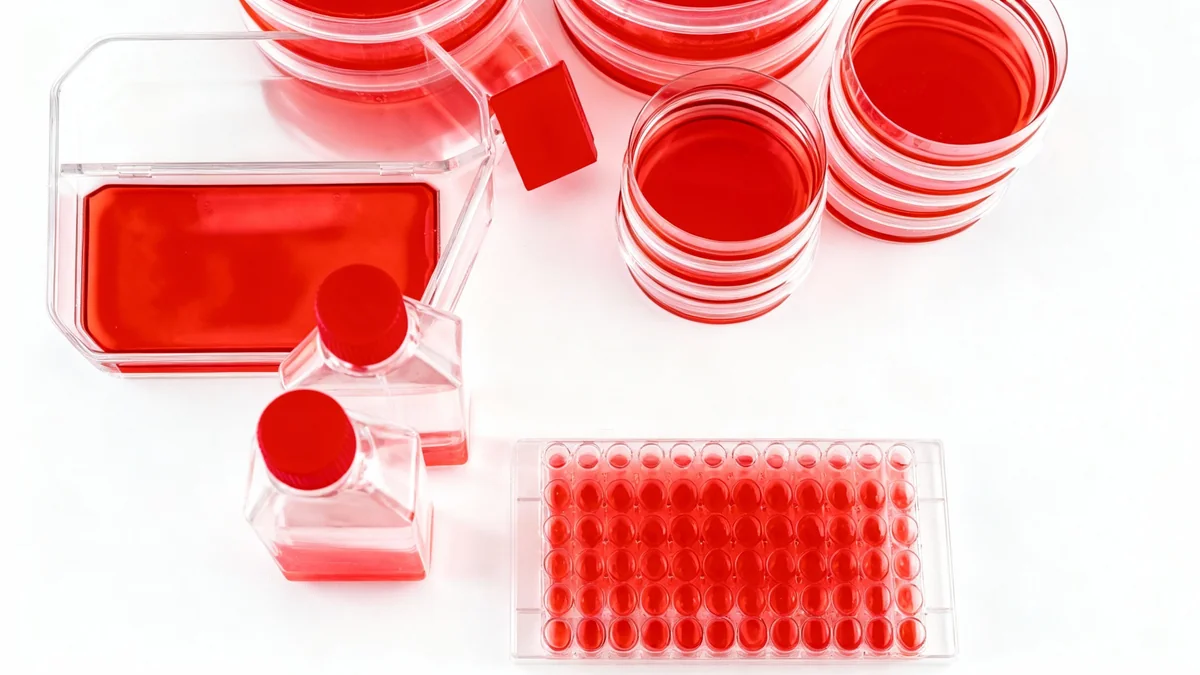

Another groundbreaking technology is the "organ-on-a-chip." These are small devices containing living human cells that mimic the structure and function of an entire organ, like a lung or kidney. TRISH is working on a plan to send these chips into deep space on uncrewed missions.

"The crazy idea we were building towards is actually to create a completely non-human tended payload that we will put in deep space with your cells," Donoviel said. These automated labs would allow scientists on Earth to get real-time data on how human tissues respond to the harsh deep space environment.

Bringing Space Advancements Back to Earth

The quest to keep astronauts healthy in space has a direct and powerful impact on life on Earth. The accelerated aging process seen in space—from bone loss to DNA damage—mirrors many conditions we face as we get older.

"Learning how different people... are repairing quickly in response to a high radiation exposure, is going to give us insights about resisting cancer," Donoviel noted. This research could also help protect healthy tissues in cancer patients undergoing radiation therapy.

The miniaturized, automated technology being developed for space missions has terrestrial applications as well. Fathi Karouia pointed out that these systems could be deployed in resource-limited settings on Earth, providing advanced diagnostic capabilities in remote areas.

Ultimately, by studying the body at its most vulnerable, scientists hope to unlock secrets that can make us all more resilient. As Karouia concluded, "It seems like by studying what's happening in space, maybe we can also leverage whatever we found for us on Earth."