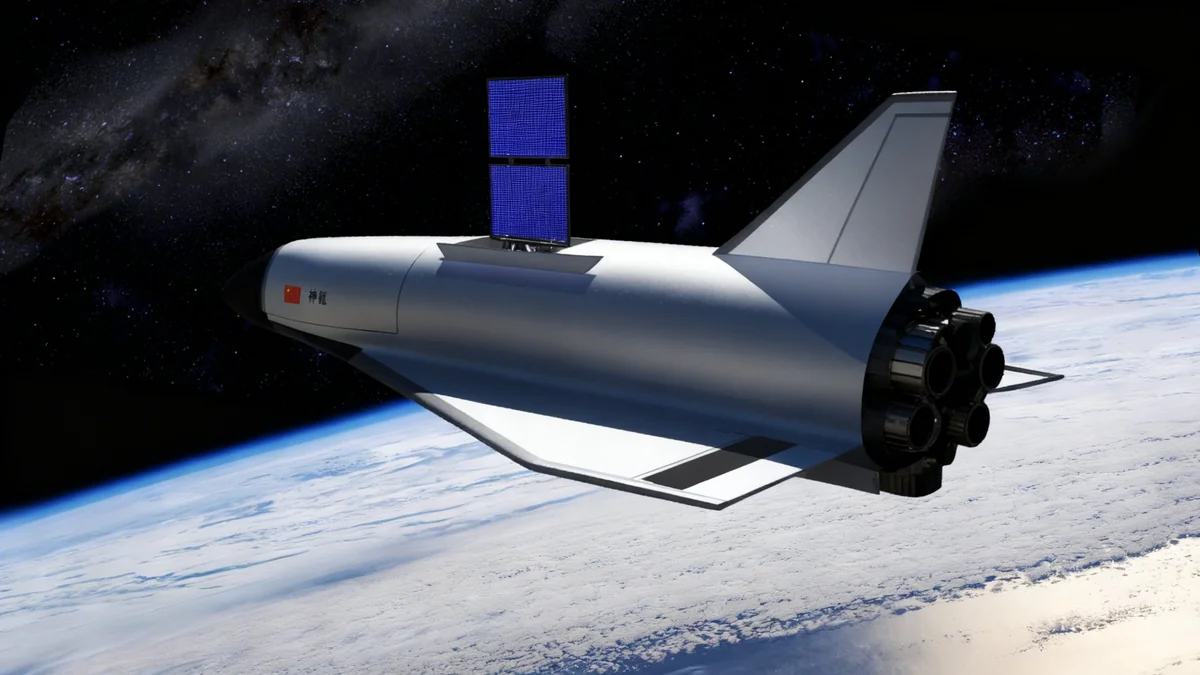

In a quiet but significant demonstration of advanced space capability, China has successfully refueled a satellite in geostationary orbit, a feat the United States pioneered nearly two decades ago but never operationalized. The maneuver highlights a growing logistical gap in space, prompting urgent calls for the U.S. to field its own operational system to maintain a strategic edge.

The operation involved the Shijian-25 spacecraft docking with and transferring fuel to the older Shijian-21 satellite. While presented as a life-extension mission, the event serves as a clear signal of China's ability to sustain and maneuver its most critical assets in a highly strategic orbital domain.

Key Takeaways

- China successfully conducted a satellite-to-satellite refueling mission in geostationary orbit in mid-2025.

- The United States demonstrated this capability with DARPA's Orbital Express in 2007 but did not pursue an operational system.

- U.S. military leaders now emphasize "dynamic space operations," which require robust in-orbit logistics like refueling and servicing.

- The U.S. Space Force plans technology demonstrations for 2026 and 2027 but faces criticism for a pace that may not match emerging threats.

A Strategic Milestone in High Orbit

China's recent achievement in space logistics was not a flashy lunar mission, but its long-term implications may be far more profound. In mid-2025, the Shijian-25 spacecraft executed a precise rendezvous and docking with its sibling, Shijian-21, nearly 36,000 kilometers above the Earth.

During this operation, Shijian-25 successfully transferred propellant, effectively refilling the older satellite's tank. This allows the serviced satellite to extend its operational life and, more importantly, maintain its ability to maneuver. In geostationary orbit (GEO), where satellites appear stationary from the ground, even small adjustments require fuel and are strategically vital for communication, surveillance, and defense.

This capability transforms satellites from disposable assets with a fixed lifespan into sustainable, adaptable platforms. For military and intelligence spacecraft, mobility is a key defensive tool against potential threats, allowing them to reposition, evade, or inspect other objects in orbit.

A History of Paused Progress

The concept of refueling satellites is not new to the United States. In 2007, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) successfully executed the Orbital Express mission, which proved that robotic spacecraft could service and refuel one another in orbit.

However, at the time, the strategic urgency was not perceived to be high. Satellites were designed to be launched and left in place for their entire 15-year lifespans, and there was no immediate push from the military to invest in the complex logistics required for in-orbit maintenance. The technology was validated and then largely shelved as a science project.

What is Dynamic Space Operations?

U.S. Space Command has increasingly pushed for a strategy known as "dynamic space operations." This doctrine shifts away from the traditional model of static, predictable satellites. Instead, it envisions a future where U.S. assets can maneuver freely and unpredictably in orbit to respond to threats, conduct inspections, and reposition for optimal coverage without the constant fear of running out of fuel.

That perspective is now rapidly changing. The rise of potential adversaries with sophisticated space capabilities has made maneuverability a critical component of space defense. Military leaders now argue that the ability to move without depleting precious fuel reserves is essential for survival in a contested space environment.

Industry Ready, Awaiting Commitment

The private sector has been ready to support this shift for years. Companies like Northrop Grumman's SpaceLogistics have already commercialized aspects of DARPA's original technology, offering life-extension services to commercial satellite operators. However, military adoption has been slow.

This lag has created a sense of frustration within the aerospace industry. Joe Anderson, a vice president at SpaceLogistics, recently highlighted the disparity in investment priorities.

“Space has been the one domain where all our money is spent on the asset, and there’s been essentially zero money spent on support and maintenance,” Anderson told an industry audience.

This approach is unique among military domains. Navies invest heavily in ports and repair depots, air forces rely on maintenance crews and aerial refueling tankers, and armies depend on vast supply chains. In space, the most unforgiving environment, assets have historically been left to fend for themselves.

The U.S. Space Force Responds

The U.S. Space Force is now taking steps to build this missing logistical backbone. The service has scheduled technology demonstrations for 2026 and 2027 to test and validate modern refueling and servicing systems. A key development is the decision to make its next-generation surveillance satellites, designated "RG-XX," fully refuelable from the start.

These new spacecraft will replace the current Geosynchronous Space Situational Awareness Program (GSSAP) satellites, which are crucial for monitoring activity in GEO but are limited by the fuel they carry at launch. Once their tanks run low, their ability to maneuver is severely restricted.

Fuel as a Strategic Reserve

For a surveillance satellite in GEO, fuel is more than just a power source; it's a strategic reserve. The ability to refuel means a satellite can:

- Respond to threats: Move away from a hostile or suspicious spacecraft.

- Conduct inspections: Approach other objects to gather intelligence.

- Change orbital position: Reposition to cover new areas of interest.

- Extend its mission: Continue operating for years beyond its original design life.

Despite these positive steps, some experts warn that demonstrations and design changes are not enough. Charles Galbreath, a retired Space Force colonel and author of a recent Mitchell Institute report on space logistics, stressed the need for scale.

“We need to take the next step and actually produce that at scale,” Galbreath said. He argued that one-off prototypes do not serve as a credible deterrent to a competitor that is building and deploying operational systems.

From Theory to Operational Reality

The sentiment is shared by former military leaders who have long advocated for this capability. Retired Space Force Lieutenant General John Shaw, a proponent of maneuverable spacecraft, noted the long delay between concept and action.

“We demonstrated refueling with Orbital Express well over 15 years ago,” Shaw stated. “Now, the Chinese have clearly shown they can do it.”

According to Shaw, the technology is mature and commercial partners are eager to build the necessary infrastructure. What remains is a firm commitment from the Department of Defense to field a complete operational architecture. This means treating space logistics not as an experiment but as a fundamental requirement for national security.

This strategic imperative extends beyond near-Earth orbit. As nations like the U.S. and China set their sights on sustained lunar operations, the same logistical challenges apply. A permanent presence on the Moon will require a robust supply chain for fuel, parts, and other resources—the very capabilities now being tested in geostationary orbit. China's recent success is not just about extending a satellite's life; it's about building the foundational skills needed for a long-term, sustainable presence in deep space.