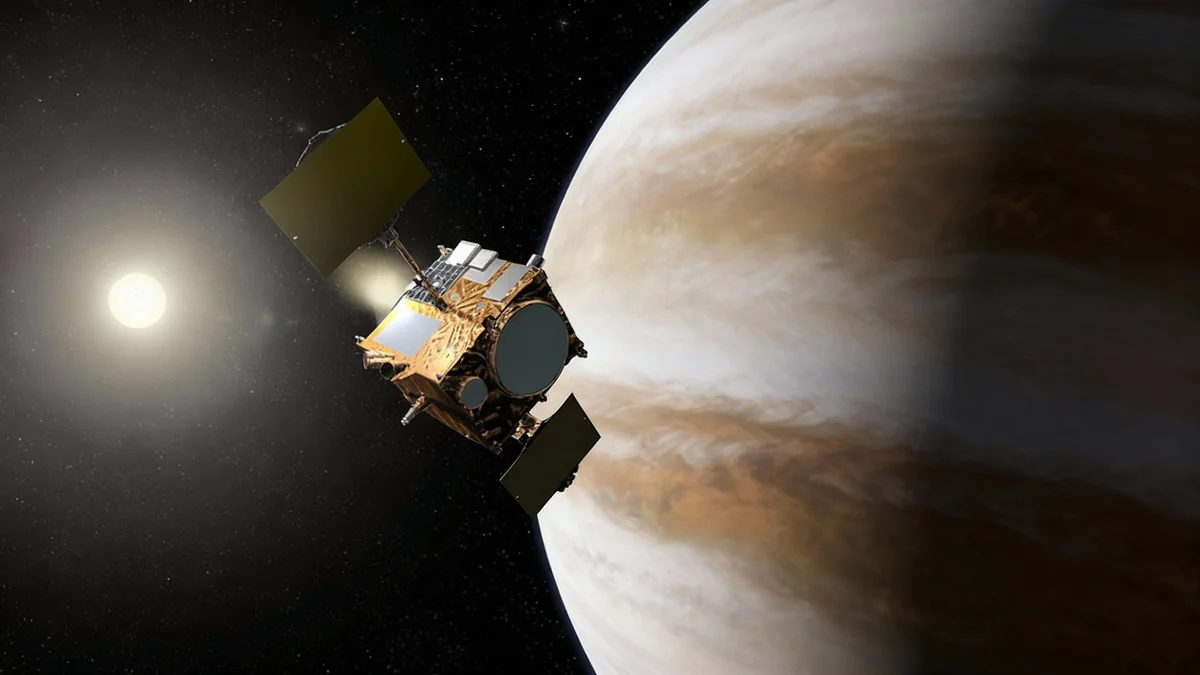

The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) has officially concluded the mission for its Akatsuki spacecraft, which had been humanity's only active probe orbiting Venus. The announcement on October 28 marks the end of a resilient mission that significantly advanced our understanding of the Venusian climate, despite facing a critical engine failure early in its journey.

After losing contact with the orbiter on May 29, 2024, mission controllers were unable to reestablish communication. Akatsuki, also known as the Venus Climate Orbiter, more than doubled its planned operational lifespan and leaves a legacy of groundbreaking discoveries about our neighboring planet's extreme atmosphere.

Key Takeaways

- JAXA declared the Akatsuki mission over after losing contact in May 2024.

- The spacecraft successfully entered Venus's orbit in 2015 after an initial engine failure in 2010.

- Akatsuki's primary discovery was identifying solar heating as the driver of Venus's atmospheric "super rotation."

- The mission's findings have implications for understanding the potential habitability of tidally locked exoplanets.

- With Akatsuki's end, Venus is left without any active orbiting spacecraft.

A Mission of Resilience and Innovation

Launched in 2010, the $300 million Akatsuki mission faced a near-catastrophic setback when its main engine failed during its first attempt to enter orbit around Venus. The spacecraft overshot the planet and entered a long, five-year orbit around the sun.

However, the JAXA team devised an audacious recovery plan. In 2015, as the probe once again approached Venus, engineers used its smaller attitude control thrusters to perform the orbital insertion burn. This maneuver, never before attempted for such a purpose, was successful, placing Akatsuki into a stable orbit around the second planet from the sun.

"With the main rocket engine damaged, the team were forced to get creative," JAXA officials stated. "Orbit insertion had never previously been achieved with such a method, but exploration has always been about redefining the impossible."

This remarkable feat of engineering allowed the mission to proceed, ultimately tripling its designed 4.5-year lifetime and producing data for nearly a decade.

Venus: Earth's Inhospitable Twin

Often called Earth's sister planet due to its similar size and mass, Venus has a dramatically different environment. Its surface temperature is hot enough to melt lead, and the atmospheric pressure is over 90 times that of Earth's at sea level. A thick, toxic atmosphere of carbon dioxide and sulfuric acid clouds completely shrouds the planet, making direct surface observation from orbit impossible.

Unlocking the Secrets of a Runaway Greenhouse

Akatsuki's primary objective was to study the climate of Venus, focusing on the thick cloud layer located between 50 and 70 kilometers above the surface. A key mystery the mission sought to solve was the phenomenon known as "super rotation."

Venus rotates incredibly slowly, with a single day lasting 243 Earth days. Its atmosphere, however, whips around the planet at incredible speeds, circling the globe in just four Earth days. Winds in this region can reach speeds comparable to high-speed bullet trains.

By continuously imaging the clouds, researchers were able to map their movement and measure their speeds. "This analysis revealed that the acceleration of the clouds depended on the local solar time, suggesting that the incredible rotation speeds were being maintained by solar heating," JAXA explained.

Akatsuki Mission by the Numbers

- Launch Date: May 20, 2010

- Venus Orbit Insertion: December 7, 2015

- Mission Cost: Approximately $300 million

- Scientific Output: 178+ published journal papers

- Designed Lifespan: 4.5 years

- Operational Duration: Nearly 9 years in orbit

Implications for Worlds Beyond Our Solar System

This discovery has significant implications for the search for life on other planets. Many exoplanets discovered so far are believed to be tidally locked to their stars, meaning one side perpetually faces the star while the other is in permanent darkness.

Scientists have debated whether such worlds could be habitable. A major concern is that the atmosphere on the dark side would freeze and collapse. However, Akatsuki's findings suggest that solar heating could drive a powerful atmospheric circulation system, redistributing heat from the dayside to the nightside and potentially stabilizing the climate enough to support liquid water.

Akatsuki also observed a massive, stationary bow-shaped feature in the upper atmosphere that persisted for several days. Researchers believe this was a large-scale gravity wave, a ripple in the atmosphere caused by air flowing over the mountainous terrain on the planet's surface below.

The Future of Venus Exploration

With Akatsuki's mission now over, there are currently no active spacecraft orbiting Venus. The planet is temporarily without a dedicated observer, leaving a gap in our continuous monitoring of its complex climate system.

Several new missions are in development, though their futures are not guaranteed. NASA is planning two missions: DAVINCI, an atmospheric probe designed to descend through the clouds, and VERITAS, an orbiter that will map the planet's surface and study its geology.

The European Space Agency (ESA) is also developing its own orbiter, EnVision, which will study the planet from its core to its upper atmosphere.

However, both NASA missions are facing potential funding challenges. The proposed 2026 budget includes significant cuts that could delay or cancel dozens of science missions, including these vital projects. The final outcome will depend on ongoing political negotiations.

For now, the scientific community will continue to analyze the vast dataset left behind by Akatsuki, a mission that defied the odds to provide a new perspective on the hellish world next door.