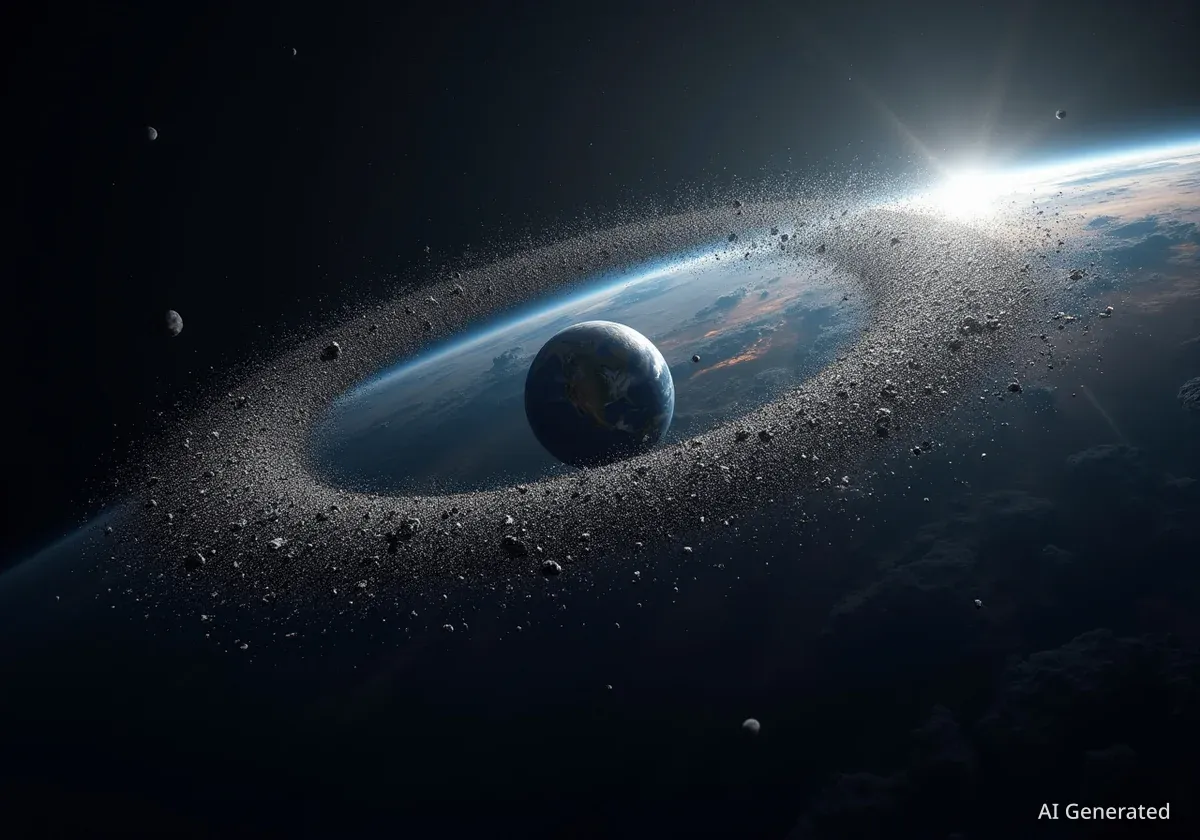

A growing cloud of human-made debris is encircling our planet, creating an increasingly hazardous environment for current and future space missions. Former NASA astronaut Mike Massimino has highlighted the escalating risks posed by millions of pieces of orbital junk, which travel at speeds capable of causing catastrophic damage to operational satellites and crewed spacecraft like the International Space Station.

The issue extends beyond immediate mission safety, threatening the long-term viability of Earth's orbit. As the volume of debris increases, so does the probability of collisions, which in turn generate even more debris. This potential chain reaction presents a significant challenge for the global space community, with experts stressing the urgent need for mitigation and cleanup strategies.

Key Takeaways

- Over 100 million pieces of space debris are estimated to be in orbit, ranging from defunct satellites to tiny paint flecks.

- Debris travels at speeds up to 17,500 mph (28,000 km/h), where even small fragments can cause catastrophic damage.

- The International Space Station frequently performs avoidance maneuvers to dodge tracked debris.

- Experts warn of a potential cascading collision effect, known as the Kessler Syndrome, which could render parts of Earth's orbit unusable.

An Invisible Hazard Above

From the ground, space appears vast and empty. In reality, the orbits around Earth are becoming progressively more crowded with refuse. This orbital debris consists of everything from spent rocket stages and defunct satellites to tiny fragments from past collisions and mission-related objects.

According to former NASA astronaut Mike Massimino, who has spent over 570 hours in space, the danger is very real. "When you're up there, you're aware that you are traveling through an environment that has these potential threats," Massimino explained. "We train for it, but the speed of these objects makes them impossible to see coming."

By the Numbers

Space surveillance networks track approximately 35,000 debris objects larger than 10 centimeters. However, models estimate there are over 1 million objects between 1 and 10 cm, and more than 100 million smaller than 1 cm. Each one poses a potential threat.

The primary danger lies in the immense kinetic energy of these objects. At orbital velocities, a metal fragment the size of a marble can strike with the force of a bowling ball traveling at over 500 mph. Such an impact could easily puncture the hull of a spacecraft, disable critical systems, or endanger an astronaut's life during a spacewalk.

The Risk to Astronauts and Satellites

The International Space Station (ISS) serves as a constant reminder of the debris threat. Its heavily shielded modules are designed to withstand impacts from smaller particles, but it is not invulnerable. To protect the station and its crew, ground control teams constantly monitor the orbital environment.

"We have to move the International Space Station on a regular basis to get out of the way of debris that we're tracking," Massimino stated, underscoring the routine nature of these life-saving maneuvers. "The concern is always for the pieces that are too small to track but still big enough to cause serious harm."

This constant threat of collision has led to the development of detailed protocols. If a piece of tracked debris is projected to pass too close to the ISS, mission controllers can fire the station's thrusters to alter its orbit. In more urgent situations where there isn't enough time to move, astronauts may be instructed to shelter in their docked spacecraft, such as the Soyuz or Crew Dragon, which can serve as lifeboats for an emergency return to Earth.

What Happens if an Astronaut is Stranded?

The scenario of an astronaut being stranded in orbit is a recurring theme in fiction, but space agencies have multiple contingency plans. Rescue protocols involve using docked spacecraft as safe havens. In the event of a disabled station, a rescue mission could be launched, though this would take time. The primary focus remains on prevention, including robust spacecraft shielding and meticulous debris tracking.

Protecting Critical Infrastructure

The danger is not limited to human spaceflight. Thousands of operational satellites providing essential services—from GPS navigation and weather forecasting to global communications and financial transactions—are also at risk. The loss of even a few key satellites could have a significant impact on daily life on Earth.

A collision involving a large satellite could create thousands of new pieces of debris, further polluting the orbital environment and increasing the risk for all other spacecraft. This highlights the interconnected nature of the problem, where a single event can have far-reaching consequences.

The Challenge of a Cascading Problem

One of the most significant long-term concerns among scientists is a theoretical scenario known as the Kessler Syndrome. Proposed by NASA scientist Donald J. Kessler in 1978, it describes a situation where the density of objects in low Earth orbit becomes so high that collisions create a cascading effect.

Each collision would generate more debris, which would then increase the probability of further collisions, leading to a chain reaction. If such an event were to occur, it could create an impenetrable field of debris that would make launching new satellites or conducting human spaceflight missions incredibly dangerous, or even impossible, for generations.

Steps Toward a Solution

Addressing the space debris problem requires a multi-faceted approach. International cooperation is key, and several strategies are being developed and implemented:

- Mitigation Guidelines: Many space agencies now require new satellites to be designed to deorbit themselves within 25 years of mission completion, either by burning up in the atmosphere or moving to a less-populated "graveyard orbit."

- Improved Tracking: Enhanced ground-based radar and optical telescopes are improving our ability to track smaller pieces of debris, providing better warnings for satellite operators and the ISS.

- Active Debris Removal (ADR): Several companies and agencies are developing experimental technologies to actively remove existing debris from orbit. These concepts include using nets, harpoons, or robotic arms to capture and deorbit large objects like defunct satellites.

While these efforts are promising, the scale of the challenge is immense. "Cleaning up space is a complex technical and political problem," Massimino noted. "But it's one we have to solve if we want to continue to explore and use space safely." The future of space exploration and our reliance on orbital technology may depend on our ability to manage the junkyard we have created above our heads.