NASA has successfully launched a series of sounding rockets from a remote Alaskan facility directly into the heart of the aurora borealis. The missions aim to unravel the complex electrical currents within the northern lights, a phenomenon that is beautiful but also linked to powerful space weather that can disrupt technology on Earth and in orbit.

Over two consecutive nights, three rockets soared into the vibrant, dancing lights above the Poker Flat Research Range near Fairbanks, gathering crucial data on mysterious "black auroras" and the overall electrical system that powers these celestial displays.

Key Takeaways

- NASA conducted two separate missions, launching three suborbital rockets from Alaska on February 9 and 10.

- The first mission, BADASS, targeted "black auroras," which are dark patches within the light show caused by an unusual upward flow of electrons.

- The second mission, GNEISS, used two rockets to create a 3D map of the electrical currents flowing within a standard aurora.

- The research is critical for understanding and predicting space weather, which can damage satellites, endanger astronauts, and disrupt power grids on Earth.

Probing the Northern Lights

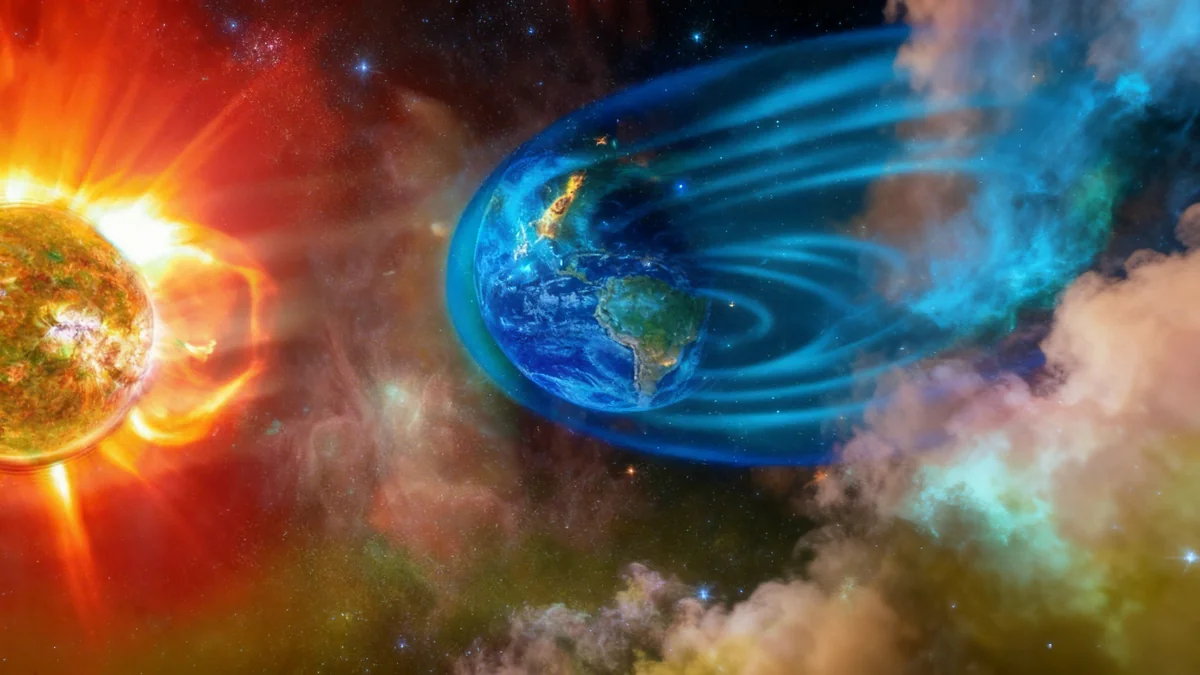

Scientists are seeking a deeper understanding of the intricate electrical circuits high in Earth's atmosphere. When energy from the sun, known as solar wind, interacts with our planet's magnetic field, it creates the stunning visual spectacle of the aurora. However, this interaction is also the source of geomagnetic storms.

To study this environment, NASA relies on sounding rockets. These are smaller, suborbital rockets designed to fly for short periods, equipped with scientific instruments that collect data as they pass through specific atmospheric phenomena before falling back to Earth. This method provides direct measurements that are impossible to obtain from ground-based instruments or satellites in orbit.

The recent launches from Alaska represent a concentrated effort to analyze the fundamental physics of these events in real time.

The BADASS Mission and Black Auroras

The first of the two missions, launched in the early morning of February 9, was named the Black and Diffuse Auroral Science Surveyor, or BADASS. Its target was a peculiar and less understood feature of the northern lights known as a black aurora.

Unlike the bright, colorful curtains of light created by electrons raining down into the atmosphere, black auroras are dark, empty patches that appear to move through the display. Scientists believe these are regions where electrons are instead being accelerated upward, away from Earth and back out into space.

Mission Profile: BADASS

- Launch Date: February 9

- Target: Black Aurora

- Peak Altitude: 224 miles (360 km)

- Objective: To measure the upward flow of electrons and understand the forces causing this reversal.

Marilia Samara, the principal investigator for the BADASS mission, confirmed that the launch was a complete success. She reported that the instruments on the rocket performed as expected and returned high-quality data. This information will be vital for scientists to model what causes the electron stream to reverse its direction, a key piece of the auroral puzzle.

A 'CT Scan' of the Aurora

A day later, on February 10, the second mission, known as the Geophysical Non-Equilibrium Ionospheric System Science (GNEISS), took flight. This ambitious project involved launching two rockets in quick succession to perform a kind of three-dimensional scan of the aurora's electrical environment.

The two rockets reached a peak altitude of 198 miles (319 km). By flying in tandem and coordinating their measurements with a network of receivers on the ground, the GNEISS mission aimed to build a comprehensive map of how electrical currents flow and dissipate within the aurora.

"It's essentially like doing a CT scan of the plasma beneath the aurora," said Kristina Lynch, the GNEISS principal investigator and a professor at Dartmouth College.

Lynch explained the core scientific question her team hopes to answer. "We want to know how the current spreads downward through the atmosphere," she stated. Understanding this energy distribution is fundamental to grasping the complete auroral circuit.

Why This Research Matters

The study of auroras is more than an academic pursuit. The same geomagnetic storms that cause brilliant auroras can have significant negative consequences:

- Satellite Damage: Storms can disrupt or permanently damage the electronics of satellites essential for communication, navigation (GPS), and weather forecasting.

- Astronaut Safety: Increased radiation during these events poses a health risk to astronauts aboard the International Space Station and on future deep-space missions.

- Power Grid Failures: Intense geomagnetic activity can induce currents in power lines on the ground, potentially overloading transformers and causing widespread blackouts.

- Communication Blackouts: High-frequency radio transmissions and air travel routes, particularly over polar regions, can be severely disrupted.

Building Better Space Weather Forecasts

The data collected by both the BADASS and GNEISS missions will be analyzed over the coming months. Scientists hope the findings will refine the models used to predict space weather. Just as meteorologists forecast hurricanes and tornadoes on Earth, space physicists work to predict the timing and intensity of solar storms.

Improved forecasting gives satellite operators, power grid managers, and airlines time to take protective measures, mitigating the potential for damage and disruption. These brief rocket flights into the Alaskan sky are a critical step toward safeguarding the technological infrastructure that modern society depends on, ensuring that the beauty of the aurora does not come at an unexpected cost.