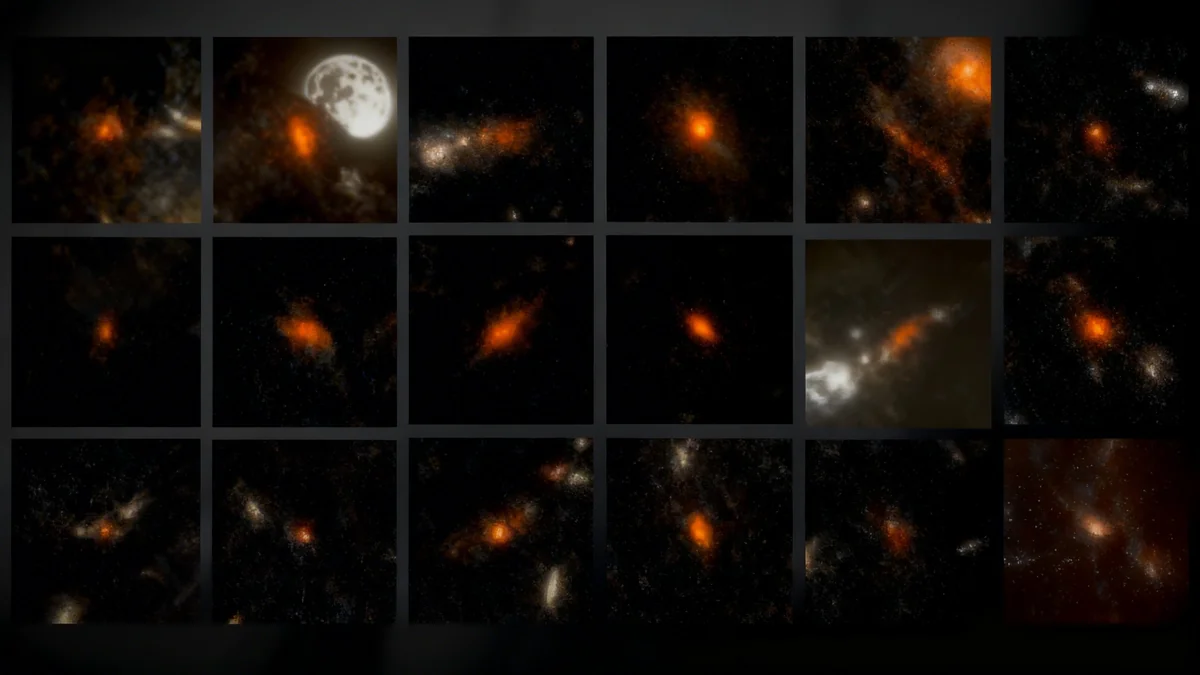

An experiment aboard the International Space Station (ISS) has successfully demonstrated that microorganisms can extract valuable metals from meteorites in microgravity. This breakthrough in biomining could pave the way for future long-duration space missions to source materials directly in space, reducing the immense cost of launching resources from Earth.

Conducted by NASA astronaut Michael Scott Hopkins, the experiment involved using a bacterium and a fungus to leach minerals from meteorite samples. The results, analyzed by researchers from Cornell University and the University of Edinburgh, show that this biological extraction process is not only feasible in space but can even be enhanced by the unique conditions of low gravity.

Key Takeaways

- Scientists successfully used a bacterium and a fungus to extract metals from meteorite samples on the ISS.

- The experiment confirmed that biomining is a viable technique for resource extraction in a microgravity environment.

- The fungus used in the study showed increased metabolic activity in space, enhancing its ability to release valuable metals like palladium and platinum.

- This research is a critical step toward developing in-space resource utilization (ISRU), which is essential for long-term human presence in space.

A New Frontier for Mining

The concept of mining in space has long been a staple of science fiction, but it is quickly becoming a practical necessity for space agencies and private companies. The goal is to establish a sustainable presence beyond Earth, whether on the Moon, Mars, or elsewhere. Shipping every necessary material from our planet is prohibitively expensive.

This experiment explored biomining, a method that uses living organisms to extract metals from rock. On Earth, this technique is used in some mining operations. The challenge was to see if it would work without the full force of gravity.

Researchers provided astronaut Michael Scott Hopkins with samples of meteorite material and two types of microbes: the bacterium Sphingomonas desiccabilis and the fungus Penicillium simplicissimum. These organisms were chosen for their differing biological mechanisms.

The Science of Biomining

The process relies on the natural metabolic functions of the microbes. As they grow, they produce organic compounds, specifically carboxylic acids. These acids act as chemical agents, attaching to minerals within the rock and dissolving them into a liquid solution.

"This is probably the first experiment of its kind on the International Space Station on meteorite," said Rosa Santomartino, a Cornell professor and the study's first author. She explained that using two distinct species was crucial. "These are two completely different species, and they will extract different things. We wanted to understand how and what."

What is In-Space Resource Utilization (ISRU)?

ISRU refers to the practice of collecting, processing, and using materials found in space to support human exploration. This can include mining asteroids for metals, extracting water ice from lunar craters to create breathable air and rocket fuel, or using Martian soil to 3D-print habitats. The primary benefit of ISRU is a massive reduction in launch mass and cost from Earth.

Surprising Results from Orbit

While the fundamental process of biomining worked as expected in space, the microgravity environment introduced some fascinating changes. The comparison between the space-based experiment and its Earth-based control group revealed significant differences in efficiency and microbial behavior.

Alessandro Stirpe, a Cornell researcher involved in the study, noted that the fungus, Penicillium simplicissimum, experienced a notable change. Its metabolism appeared to be altered by the space environment, leading it to produce more of the carboxylic acids necessary for extraction.

"It turns out that space changed the fungus' microbial metabolism, which allowed it to increase molecule production, including carboxylic acids. This enhanced the release of palladium, as well as platinum and other elements."

This enhanced performance is a promising sign. It suggests that some biological processes might not just be viable but could actually be more effective in space. However, the results were not uniform across the board.

Valuable Space Rocks

The metals targeted in this study are highly valuable. Palladium, a rare precious metal, has critical applications in electronics and catalytic converters. A small amount of palladium can be worth thousands of dollars, making asteroid mining an economically attractive prospect for future commercial ventures.

Complex Interactions

The researchers emphasized the complexity of the findings. The rate at which metals were extracted varied greatly depending on several factors:

- The specific microbe used: The bacterium and fungus had different extraction efficiencies.

- The target metal: Some metals were released more easily than others.

- The gravity conditions: The results in microgravity differed from those on Earth.

"Another complex but very interesting result, I think, is the fact that the extraction rate changes a lot depending on the metal that you are considering, and also depending on the microbe and the gravity condition," Santomartino stated. This highlights that there is no one-size-fits-all solution for biomining in space. Future systems will likely need to be tailored to specific microbes and target materials.

The Future of Building in Space

This successful demonstration of biomining is a significant milestone. As companies like Astroforge develop more mechanical methods using lasers and magnets, this biological approach offers a complementary or alternative pathway for resource extraction.

Using microbes could have advantages, such as lower energy requirements and the ability to self-replicate, making it a potentially sustainable and long-term solution. The ability to mine asteroids and other celestial bodies will be a cornerstone of future space exploration.

Whether for building habitats on Mars, manufacturing tools in orbit, or producing rocket fuel far from Earth, harnessing the resources of space is the key to humanity's future beyond our home planet. This experiment shows that some of our smallest biological allies could play one of the biggest roles in that endeavor.