To prepare for the immense challenges of sending humans to Mars and the Moon, scientists are not just building rockets; they are creating simulated space environments right here on Earth. Known as analog missions, these projects place small crews in isolated habitats in some of the planet's most extreme locations to study the psychological and physical demands of long-duration spaceflight.

From the volcanic slopes of Hawaii to research stations in Antarctica, these missions are crucial for understanding how to keep astronauts safe and effective millions of miles from home. Participants live under strict protocols, facing resource rationing, communication delays, and the immense pressure of confinement, providing invaluable data for future interplanetary journeys.

Key Takeaways

- Analog missions are ground-based simulations that replicate the conditions of space exploration on the Moon or Mars.

- These missions test everything from equipment and procedures to crew psychology, team dynamics, and stress management in isolated, confined environments.

- Locations are chosen for their resemblance to extraterrestrial landscapes, including volcanic fields in Hawaii, deserts in Utah, and polar regions.

- Crews, often composed of scientists and engineers, live for weeks or months with rationed food and water, limited communication, and a highly structured daily schedule.

What Are Analog Missions?

Before humanity takes its next giant leap to another planet, extensive preparation is required on the ground. Analog missions serve as a critical dress rehearsal for space exploration, allowing researchers to study the human element of these complex endeavors without ever leaving Earth.

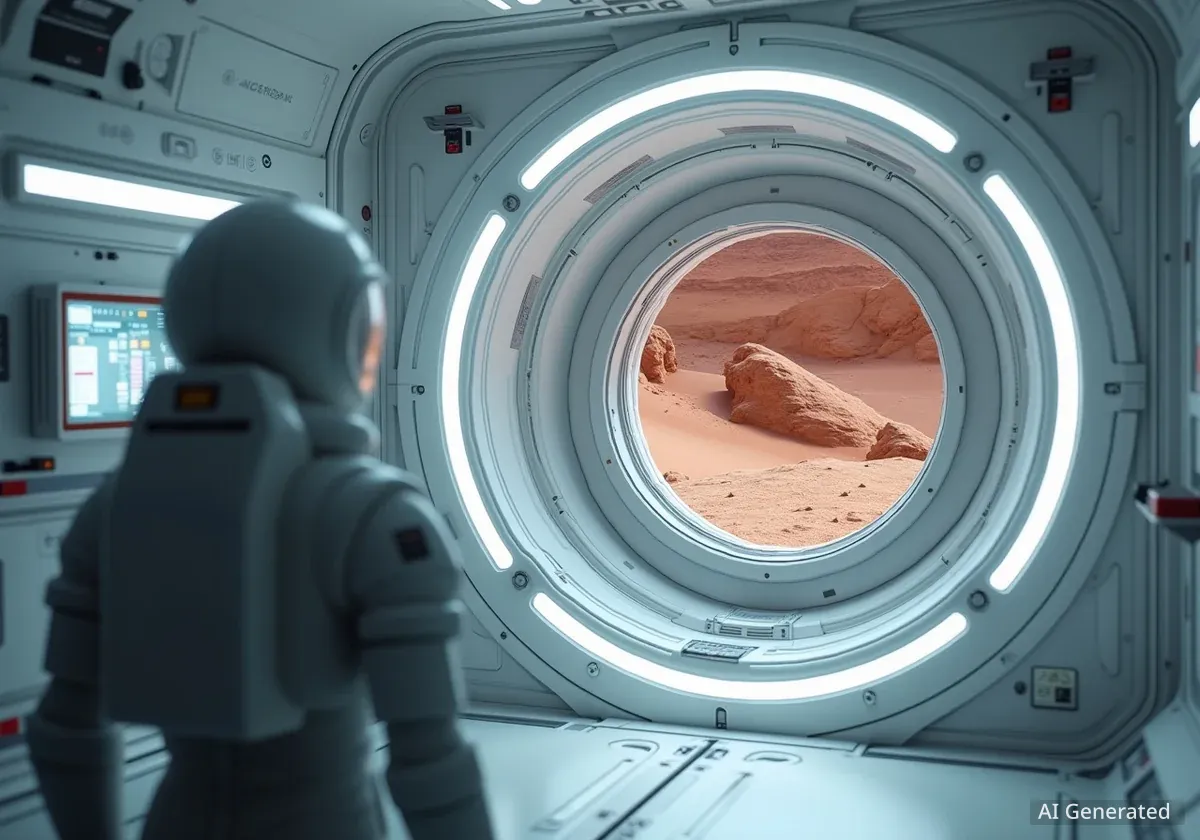

These simulations are designed to mirror specific aspects of a real mission. They can take place in habitats built to replicate spacecraft living quarters or in natural environments that are geologically similar to the Moon or Mars. The goal is to identify potential problems—whether with technology, procedures, or human behavior—and solve them before a multi-billion dollar mission is at stake.

For example, a simple task like using a wrench becomes significantly more difficult while wearing a bulky, pressurized spacesuit. Testing this in a simulated environment on Earth allows engineers to make necessary adjustments to tools and suits. Similarly, studying how a small crew interacts while confined for months provides crucial insights into selecting the right team for a three-year mission to Mars.

From Deserts to Undersea Labs

NASA and other space agencies utilize a diverse range of locations for analog missions. Each site offers unique conditions to simulate different aspects of space travel. Notable examples include the Mars Desert Research Station in Utah, where the arid landscape mimics the Red Planet, and Aquarius, an undersea research station off the Florida coast that simulates the isolation and hostile environment of space.

A World of Extreme Environments

Choosing the right location is fundamental to a successful analog mission. Scientists seek out Earth's most extreme and isolated places to best replicate the conditions astronauts will face on other worlds. These environments provide a realistic backdrop for testing and training.

Popular sites include:

- Volcanic Terrains: Locations like Mauna Loa in Hawaii offer landscapes remarkably similar to the Moon and Mars, with basaltic rock and vast, desolate fields. The HI-SEAS (Hawaii Space Exploration Analog and Simulation) habitat is located here.

- Deserts: The dry, rocky deserts of Utah and Arizona, including the famous Meteor Crater, are used to simulate Martian surface operations and geological fieldwork.

- Polar Regions: The extreme cold, isolation, and prolonged darkness of Antarctica provide a powerful analog for the psychological challenges of long-duration missions.

One planetary scientist who participated in a 28-day lunar surface simulation at the HI-SEAS facility on Mauna Loa described the experience as a deep dive into the human factors of space exploration. The mission was designed to study crew dynamics and psychology in extreme isolation, providing data that helps mission planners understand how to build resilient and cohesive teams.

The HI-SEAS Habitat

Located on the slopes of Mauna Loa, the HI-SEAS habitat is a geodesic dome where crews have lived for up to a year at a time. The volcanic terrain is so similar to Mars that it allows for realistic geological surveys and Extra-Vehicular Activities (EVAs), or "spacewalks."

Life Inside the Simulation

Daily life for an analog astronaut is highly structured and demanding. Crews are typically composed of individuals with backgrounds similar to those in the official astronaut corps—scientists, engineers, and medical professionals. They are selected not only for their skills but also for their ability to work well in a team under intense pressure.

A Rigorous Schedule

A typical day is scheduled from morning to night. A participant in the HI-SEAS mission recalled a schedule that ran from approximately 6:30 a.m. to 10:00 p.m. Daily tasks included a mix of individual and group activities designed to measure performance and stress levels.

These activities could range from daily cognitive tests to complex group tasks like virtual 3D Tetris, with researchers remotely monitoring interactions. Performance fluctuations in these tasks serve as a key indicator of individual well-being and group cohesion.

"We were kept busy all day, as certain everyday tasks, such as cooking, required more effort than they might need in our normal lives. Preparing nutritionally balanced and palatable meals while rationing our very limited resources was hard, but it also provided opportunities to get creative."

On alternating days, crews conduct EVAs. These excursions outside the habitat require them to don mock spacesuits, complete with helmets and air supply systems. During these hours-long expeditions, they perform geological surveys, collect samples, and practice exploration procedures, all while following strict safety protocols.

Resource Management is Key

Life in the habitat is a constant exercise in resource management. Food is almost entirely freeze-dried or powdered, supplemented only by what can be grown in small hydroponic gardens. There are no resupply missions.

Water is even more strictly rationed. This impacts everything, including personal hygiene. Showers are limited to perhaps once or twice a week, often using just a bucket of water. Laundry might be done only once during a month-long mission, forcing crew members to work together in close quarters.

These constraints are not just for realism; they are a critical part of the psychological study. How a crew manages limited resources and resolves the inevitable conflicts that arise is vital information for planning real missions where survival depends on it.

The Human Element

Ultimately, the most valuable data from analog missions relates to the human element. Technology can be tested and re-tested, but predicting human behavior under the combined stress of isolation, confinement, and constant danger is far more complex.

To maintain morale, crews find ways to adapt and bond. They share pre-saved movies, trade physical books, and play board games. In one mission, a crew member managed to download the daily Wordle puzzle, allowing the isolated team to still feel connected to friends and family back home. Another crew even managed to bake a birthday cake using protein powder and cocoa powder.

These small acts of normalcy and creativity are not trivial; they are survival mechanisms. They demonstrate the resilience and ingenuity that will be essential for the first humans who venture to Mars.

By living and working in these Earth-based simulations, analog astronauts are not just playing make-believe. They are generating the knowledge needed to turn science fiction into reality, ensuring that when we finally set foot on another planet, we are as prepared as we can possibly be.