The International Space Station (ISS) represents humanity's most significant step toward living off-planet, but a closer look reveals a venture entirely dependent on Earth. With a daily cost exceeding $1 million per astronaut, the station requires a constant stream of supplies from the ground, challenging the notion of self-sufficient life in orbit.

This continuous reliance on Earth for basic survival necessities like air, water, and food raises fundamental questions about the feasibility and sustainability of long-term space colonization. The dream of an extraterrestrial future confronts a harsh reality of immense financial, environmental, and biological costs.

Key Takeaways

- The International Space Station is not self-sufficient and relies on frequent resupply missions from Earth for oxygen, water, food, and fuel.

- The cost to support a single astronaut on the ISS is over $1 million per day, funded by an annual budget of more than $2.8 billion.

- Astronauts in space face radiation levels over 100 times higher than on Earth, significantly increasing lifetime cancer risk.

- The environmental impact of space travel is substantial, with the fuel for resupply missions creating a massive carbon footprint.

- Arguments comparing space exploration to historical colonization or evolution fail to account for the hostile, resource-barren nature of space.

A Lifeline to Earth: The Reality of the ISS

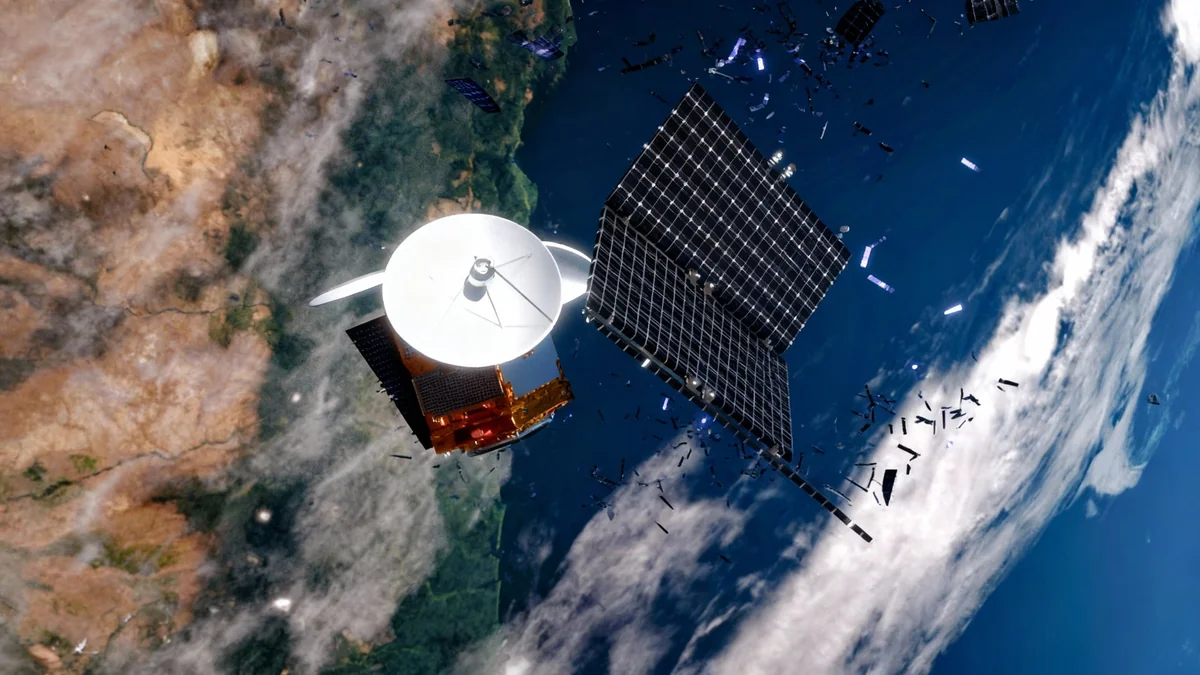

For nearly 25 years, the International Space Station has been continuously occupied, orbiting approximately 400 kilometers above our planet. While a remarkable technological achievement, the station is less of an independent outpost and more of a remote camp tethered to Earth by an invisible, and very expensive, supply chain.

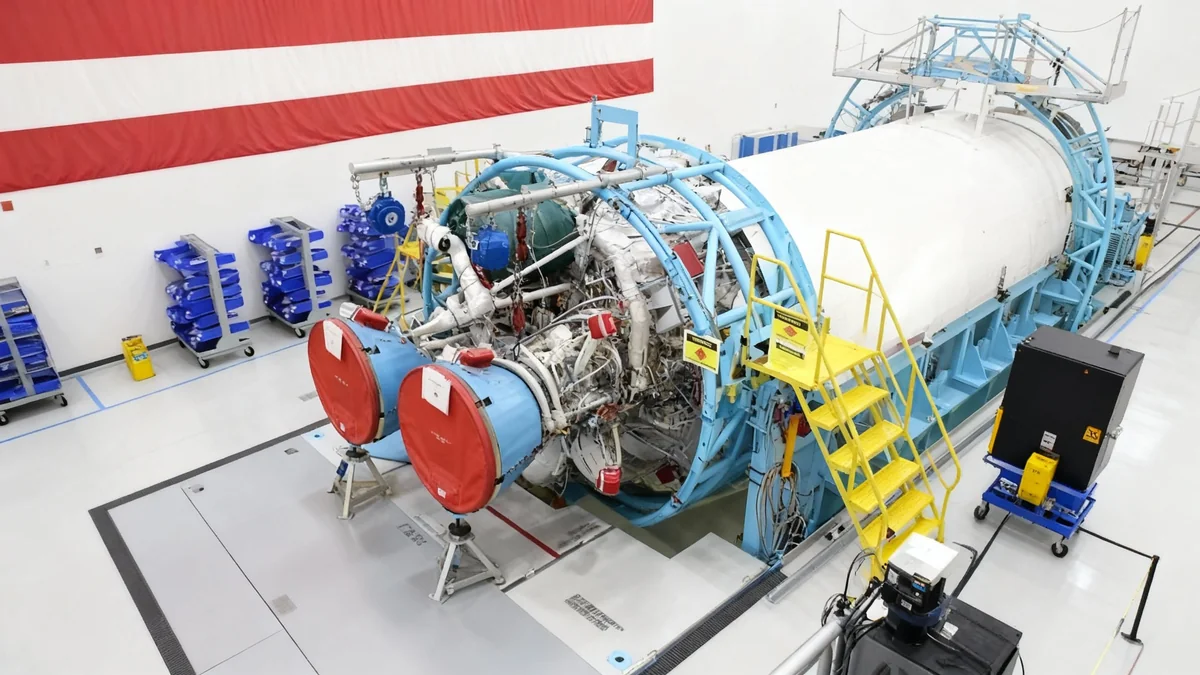

Resupply missions, occurring roughly every 45 days, are critical for survival. These missions deliver essentials that cannot be fully sustained on board. Despite advanced technology, the station's life support systems only recycle between 42% and 47% of the oxygen crew members need. The rest must be shipped from Earth.

Water recycling is more efficient at 90%, yet resupply rockets still deliver hundreds of liters of water regularly to replenish the system. Without these deliveries, the crew would face dehydration within a year.

Constant Correction Required

The ISS is in a low-Earth orbit where atmospheric drag constantly slows it down, causing its altitude to drop by about 100 meters each day. To counteract this decay and prevent a fiery reentry, the station must be periodically boosted. This process consumes approximately 7,000 kilograms of propellant annually, another critical resource that must be launched from Earth.

This constant need for oxygen, water, fuel, and food effectively creates logistical tethers to the ground. The ISS is not truly living *in* space but rather surviving there with continuous, high-cost assistance from Earth.

The Staggering Price Tag of Off-World Living

The financial investment required to keep just a handful of humans in orbit is immense. The annual operating budget for the ISS is at least $2.8 billion, which breaks down to more than $1 million per day for each of the typical seven crew members.

This figure doesn't even include the initial $150 billion construction cost. To put it in perspective, a single bottle of water, if priced based on its share of the operational cost, would be valued at tens of thousands of dollars.

"For me the single overarching goal of human space flight is the human settlement of the solar system, and eventually beyond. I can think of no lesser purpose sufficient to justify the difficulty of the enterprise, and no greater purpose is possible."

- Michael Griffin, Former NASA Administrator (2003)

Historical and future missions carry even more staggering price tags. The Apollo program, which sent astronauts to the Moon, would cost an estimated $300 billion in today's dollars. Proposed missions to Mars are projected to cost around $500 billion for a 2.5-year trip, placing the daily cost per person at roughly $100 million.

The Environmental Toll

Beyond the financial numbers, the environmental footprint of space travel is significant. The approximately eight resupply missions to the ISS each year burn through about 2,750 tons of propellant. The hydrocarbon fuel portion alone is equivalent to the gasoline needed to drive a car 50,000 kilometers every single day.

According to analysis by physicist Tom Murphy, every hour a person spends in space carries an environmental impact equivalent to 2,000 hours of an average global citizen on Earth. This suggests that the effort to leave our planet may ironically contribute to its degradation.

An Invisible Threat: Radiation Beyond Earth's Shield

One of the most serious and unavoidable dangers of long-term space habitation is radiation. While Earth's magnetic field offers some protection, it is our atmosphere that serves as the primary shield.

Understanding Radiation Doses

Radiation exposure is measured in milli-Sieverts (mSv). An average person on Earth receives about 2 mSv per year. On the ISS, that number jumps to between 160 and 320 mSv. On the surface of the Moon or Mars, it's about 300 mSv per year—more than 100 times the terrestrial dose.

This constant bombardment by cosmic rays poses a severe health risk. A cumulative dose of one Sievert (1,000 mSv) is estimated to create a 5.5% chance of developing a fatal cancer. A lifetime on Mars or the Moon would expose a colonist to around 7 Sieverts, which would nearly double their lifetime cancer risk from 40% to 80%.

Living in underground shelters could mitigate this risk, but it presents a grim picture of extraterrestrial life: a choice between confinement in subterranean caves or a significantly shortened lifespan due to cancer. This reality is a far cry from the expansive, exploratory visions often depicted in popular culture.

A Frontier Unlike Any Other

Proponents of space colonization often draw parallels to past human achievements, framing space as the "final frontier." However, these comparisons overlook fundamental differences.

Common arguments include:

- Evolutionary Progress: The idea that life moved from water to land and now must move to space is a flawed analogy. Each evolutionary step on Earth provided access to new resources and safety from predators. Space offers the opposite: it is hostile and devoid of sustenance.

- Historical Colonization: When humans crossed oceans to settle new continents, they arrived in places with breathable air, drinkable water, and edible food. Planets like Mars offer none of these. Every resource for survival must be manufactured or transported at incredible cost.

Living in space is less like settling a new land and more like performing a complex, high-risk stunt. In 1958, two pilots managed to stay airborne in a small Cessna airplane for 65 days, refueling from a moving truck on the ground. This feat, while impressive, did not lead to permanent airborne cities. It was a demonstration of possibility, not a blueprint for a new way of life.

The current state of space habitation appears more akin to this type of elaborate stunt than the first baby steps toward a self-sustaining future. Without a clear, practical purpose beyond the fantasy of colonization, the immense expenditure of resources and assumption of risk become difficult to justify.