The International Space Station (ISS), a symbol of global scientific cooperation for over two decades, is scheduled for decommissioning in 2030. In preparation, NASA is actively fostering the development of commercial space stations, shifting its role from an operator to a customer in low-Earth orbit (LEO).

Key Takeaways

- The International Space Station is set to be deorbited into the Pacific Ocean in 2030 after more than 30 years of service.

- NASA is transitioning to a commercial model, where private companies will own and operate space stations in low-Earth orbit.

- High maintenance costs for the aging ISS are a primary driver for this strategic shift towards privatization.

- Companies like Vast Space, along with nations like China and India, are developing their own space stations, creating a new competitive landscape.

The End of an Era for the International Space Station

Launched in 1998, the International Space Station has been a cornerstone of human space exploration. It has continuously hosted astronauts since November 2000, serving as a unique microgravity laboratory for scientific research.

The station is a collaborative project among five major space agencies: NASA (United States), Roscosmos (Russia), the European Space Agency (ESA), the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA). Over its lifetime, it has welcomed more than 300 individuals from 26 different countries.

ISS by the Numbers

- Operational Since: 1998

- Original Planned Lifespan: 15 years

- Scheduled Decommissioning: 2030

- Size: The largest space station ever constructed.

The ISS is divided into two main sections. The Russian Orbital Segment (ROS) is operated by Roscosmos, while the United States Orbital Segment (USOS) is shared among NASA and the other international partners. This structure has demonstrated a framework for peaceful international cooperation in space for decades.

However, after operating well beyond its initial 15-year life expectancy, the station is aging. The mounting costs of maintenance and operations have prompted NASA to plan for a controlled deorbit, which will see the station descend into a remote area of the Pacific Ocean known as Point Nemo.

NASA's Shift to a Commercial Model in Orbit

The retirement of the ISS does not signal an end to American presence in low-Earth orbit. Instead, it marks a strategic pivot toward a new economic model. NASA is actively supporting private industry to develop commercial replacements through its Commercial Low-Earth Orbit Destinations (CLD) program.

The primary motivation for this shift is financial. By transitioning from owning and operating its own space station to leasing services from commercial providers, NASA anticipates significant cost savings. This new model allows the agency to redirect substantial funds toward its deep space exploration goals, including the Artemis missions to the Moon and future missions to Mars.

From Operator to Customer

Under the new plan, private companies will own and operate their space stations. NASA will act as an anchor tenant, purchasing services such as research time, crew accommodation, and cargo transport. This approach is designed to stimulate a robust commercial economy in LEO, serving various customers including other nations, private researchers, and even space tourists.

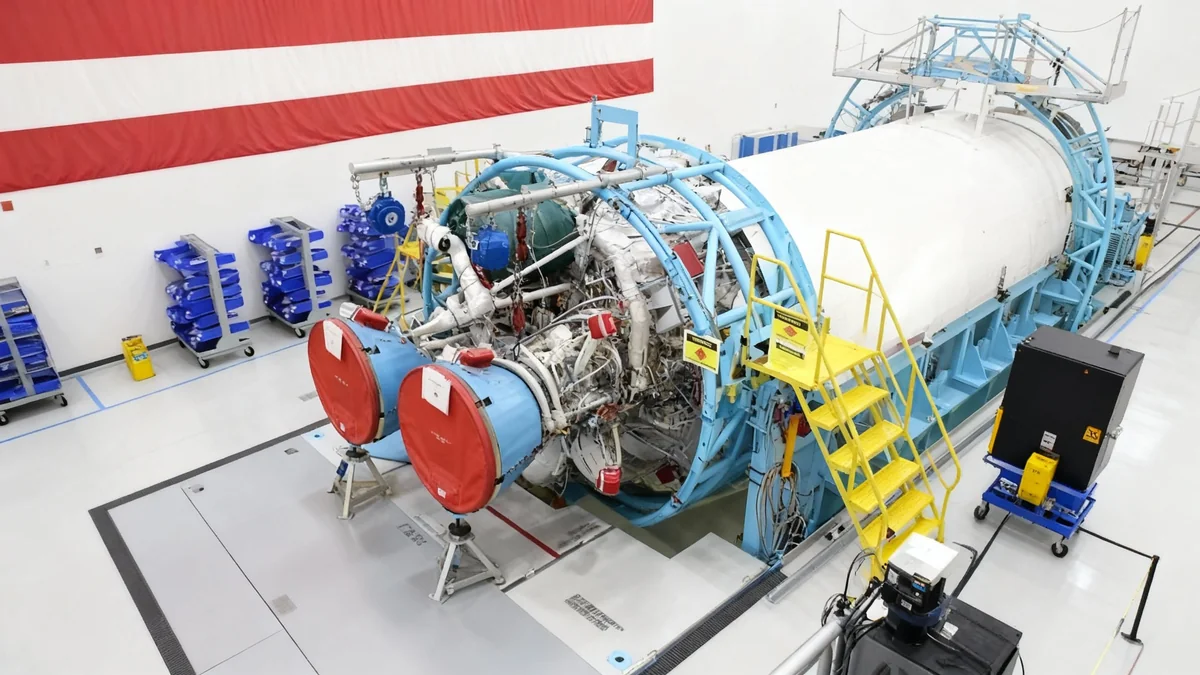

This public-private partnership model is not new for NASA. It mirrors the success of the Commercial Crew and Commercial Resupply Services programs, which have relied on companies like SpaceX and Northrop Grumman to transport astronauts and cargo to the ISS, ending America's reliance on Russian Soyuz rockets.

The New Players in the Commercial Space Race

Several American companies and international powers are positioning themselves to lead in the post-ISS era. The competition to build the next generation of orbital habitats is already underway, with distinct projects taking shape globally.

American Commercial Ventures

In the United States, one of the prominent contenders is Vast Space. The company is developing Haven-1, which aims to be the world's first commercial space station. This venture highlights the growing role of private capital and innovation in shaping the future of space infrastructure.

International Competition

The global landscape is also evolving rapidly. China has already made significant progress with its Tiangong Space Station. Construction is complete, and the station is fully operational in orbit. China has expressed its intent to open Tiangong to international collaboration, positioning it as a potential successor to the ISS for global researchers.

Meanwhile, India is also advancing its space ambitions. The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) has announced plans to launch its own space station, with a target date of 2035. This move underscores the growing number of nations capable of independent space operations.

The shift towards multiple orbital platforms operated by different entities marks a fundamental change from the single, government-led structure of the ISS era. This could lead to a more diverse and dynamic ecosystem in low-Earth orbit.

Designing Habitats Beyond the Laboratory

Future space stations are being designed with broader applications in mind. While scientific research will remain a core function, these new platforms will be more than just orbiting laboratories. The vision is to create sustainable, multi-purpose habitats.

Design concepts include dedicated modules for various activities:

- Tourism and Hospitality: Areas designed to accommodate private astronauts and space tourists.

- In-Space Manufacturing: Facilities for producing unique materials in microgravity, such as fiber optics or pharmaceuticals.

- Microgravity Agriculture: Sections dedicated to growing food in space, which is crucial for long-duration missions.

The goal is to build self-sustaining ecosystems where people can live and work for extended periods. This requires innovations in life support systems, radiation shielding, and closed-loop resource management to create a truly sustainable human presence in space.

Unanswered Questions for the Future Space Economy

As the transition to a commercialized LEO progresses, several important questions remain. One key area of concern is the process for awarding contracts. Observers are watching to see how NASA will balance commercial interests with the continued pursuit of fundamental scientific discovery.

Another significant challenge is maintaining the spirit of peaceful international cooperation that defined the ISS. With multiple stations operated by different countries and private entities, establishing a common framework for traffic management, safety standards, and legal jurisdiction will be critical.

Key Challenges Ahead

- Ensuring fair and transparent contract awards.

- Establishing international norms for a multi-station environment.

- Maintaining a focus on scientific research amid commercial pressures.

- Managing the complex geopolitics of space.

Until the ISS is decommissioned in 2030, NASA and its partners will continue to conduct vital research while managing the handover to the commercial sector. The coming years will be a critical period, setting the stage for a new, more economically diverse chapter in human spaceflight.