Approximately 74,000 years ago, the Toba supervolcano in present-day Indonesia erupted in one of the largest explosive events of the last 2.5 million years. For decades, scientists debated whether this eruption plunged the planet into a volcanic winter and nearly wiped out humanity. New archaeological evidence suggests a different story: a story of resilience and adaptation.

Instead of causing a global collapse, research from archaeological sites across Africa and Asia indicates that early human populations not only survived the cataclysmic event but, in some cases, developed new technologies and behaviors in its aftermath. This challenges long-held theories about a near-extinction event and highlights the remarkable adaptability of our ancestors.

Key Takeaways

- The Toba supereruption 74,000 years ago was over 10,000 times larger than the 1980 Mount St. Helens eruption.

- The long-standing "Toba catastrophe hypothesis" suggested the eruption caused a population bottleneck, reducing humanity to fewer than 10,000 individuals.

- Archaeological evidence from sites in South Africa, Ethiopia, and Asia shows continuous human occupation and even technological advancement after the eruption.

- Scientists use microscopic volcanic glass, or cryptotephra, to precisely date archaeological layers and connect them to the Toba event.

- The findings suggest early humans were highly resilient and adaptable, able to survive extreme environmental changes.

A Planet-Altering Event

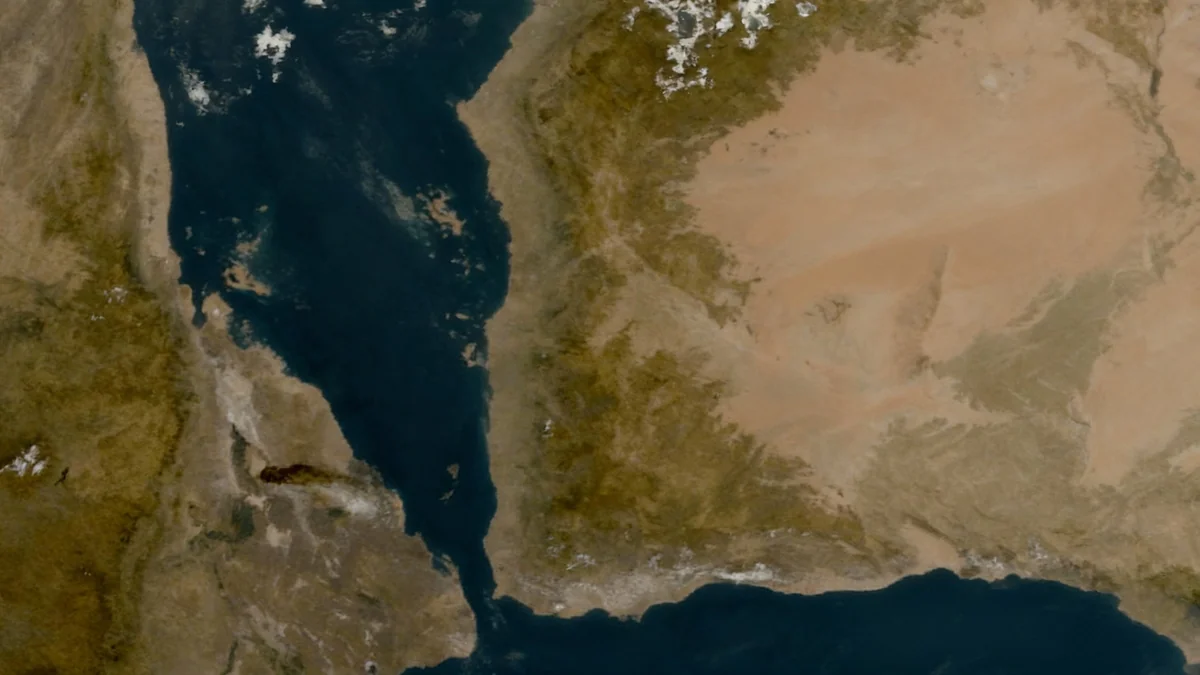

The scale of the Toba eruption is difficult to comprehend. Located on the island of Sumatra, the volcano ejected an estimated 2,800 cubic kilometers (672 cubic miles) of ash and rock into the atmosphere. This material was enough to blanket vast regions of the globe, creating a crater that now holds Lake Toba, a body of water roughly 100 kilometers long and 30 kilometers wide.

The immediate consequences would have been devastating. Sunlight would have been significantly dimmed, potentially triggering a period of global cooling that could have lasted for years. Acid rain would have poisoned water sources, and thick ash deposits would have smothered vegetation and animal life across entire ecosystems.

By the Numbers: The Toba Supereruption

- Volume of Ejecta: 2,800 km³

- Comparison: Over 10,000 times larger than the 1980 Mount St. Helens eruption.

- Crater Size: 100 km by 30 km (62 by 18 miles).

- Time Period: Approximately 74,000 years ago.

For many years, this event was linked to a significant moment in human history. Genetic studies of modern human DNA suggest our species experienced a "genetic bottleneck" around the same time, an event where the population shrinks dramatically, reducing genetic diversity. The Toba catastrophe hypothesis proposed that the eruption was the direct cause of this near-extinction event.

Uncovering the Story in Volcanic Glass

Testing the Toba catastrophe hypothesis requires connecting the eruption directly to the archaeological record of human activity. Scientists achieve this by searching for a specific type of evidence: tephra, the material ejected by a volcano. While larger pieces of rock and ash fall closer to the source, microscopic shards of volcanic glass known as cryptotephra can travel thousands of kilometers on atmospheric currents.

Archaeologists carefully excavate sites layer by layer, collecting soil samples. Back in the laboratory, they undertake the painstaking process of isolating these tiny, invisible glass shards from the dirt.

"This process can feel like looking for a needle in a haystack and can take months to complete for one site," explains Jayde N. Hirniak, a researcher specializing in past volcanic eruptions.

Each volcanic eruption has a unique chemical signature, like a fingerprint. By analyzing the chemical composition of the cryptotephra, researchers can confirm if it originated from the Toba eruption. Finding this Toba fingerprint within an archaeological site provides a precise time marker, allowing scientists to see what happened to human populations before, during, and after the event.

A Narrative of Resilience Emerges

While the Toba catastrophe hypothesis painted a grim picture of human survival, the evidence uncovered at archaeological sites tells a story of remarkable resilience.

Thriving in South Africa

At Pinnacle Point 5-6, a coastal site in South Africa, researchers discovered a layer of Toba cryptotephra. Critically, the archaeological layers show that humans lived there continuously. There was no evidence of abandonment. In fact, human activity at the site increased after the eruption, and new technological innovations appeared in the archaeological record shortly thereafter, demonstrating a high degree of adaptability.

Adapting in Ethiopia

A similar story unfolded at Shinfa-Metema 1, an archaeological site in the lowlands of Ethiopia. Here too, Toba's volcanic glass was found in layers containing evidence of human activity. The people in this region adapted to the changing environment by focusing on fishing in seasonal rivers and small waterholes. Around the time of the eruption, they also appear to have adopted more advanced hunting tools, such as the bow and arrow. This behavioral flexibility was key to their survival.

What is a Genetic Bottleneck?

A genetic bottleneck occurs when a population undergoes a drastic reduction in size due to events like natural disasters, disease, or famine. This event significantly reduces the genetic diversity of the population because many genetic lineages are lost. The survivors' genetic makeup then becomes the foundation for all future generations, resulting in a less diverse gene pool.

Further evidence from sites in Indonesia, India, and China supports this pattern of continuity and adaptation. The accumulating data suggests that while the Toba eruption was a massive global event, it may not have been the primary driver of the population bottleneck seen in human genetics. Our ancestors were not passive victims of the disaster; they were active survivors who adjusted their strategies to cope with a changing world.

Lessons for the Future

The story of human survival after the Toba supereruption provides valuable insights into our species' capacity to endure catastrophic events. While the world is very different today, the core lesson of adaptability remains relevant.

Modern society is far more prepared for volcanic events than our ancestors were 74,000 years ago. Global monitoring programs, such as the USGS Volcanic Hazards Program, track active volcanoes and provide early warnings to mitigate risk. We have technology and infrastructure that were unimaginable to Stone Age humans.

However, the archaeological record serves as a powerful reminder that our species is defined by its ability to innovate and adapt in the face of immense challenges. By studying how past populations navigated climate change and natural disasters, we can better understand the conditions that foster resilience and apply those lessons to the challenges of the future.