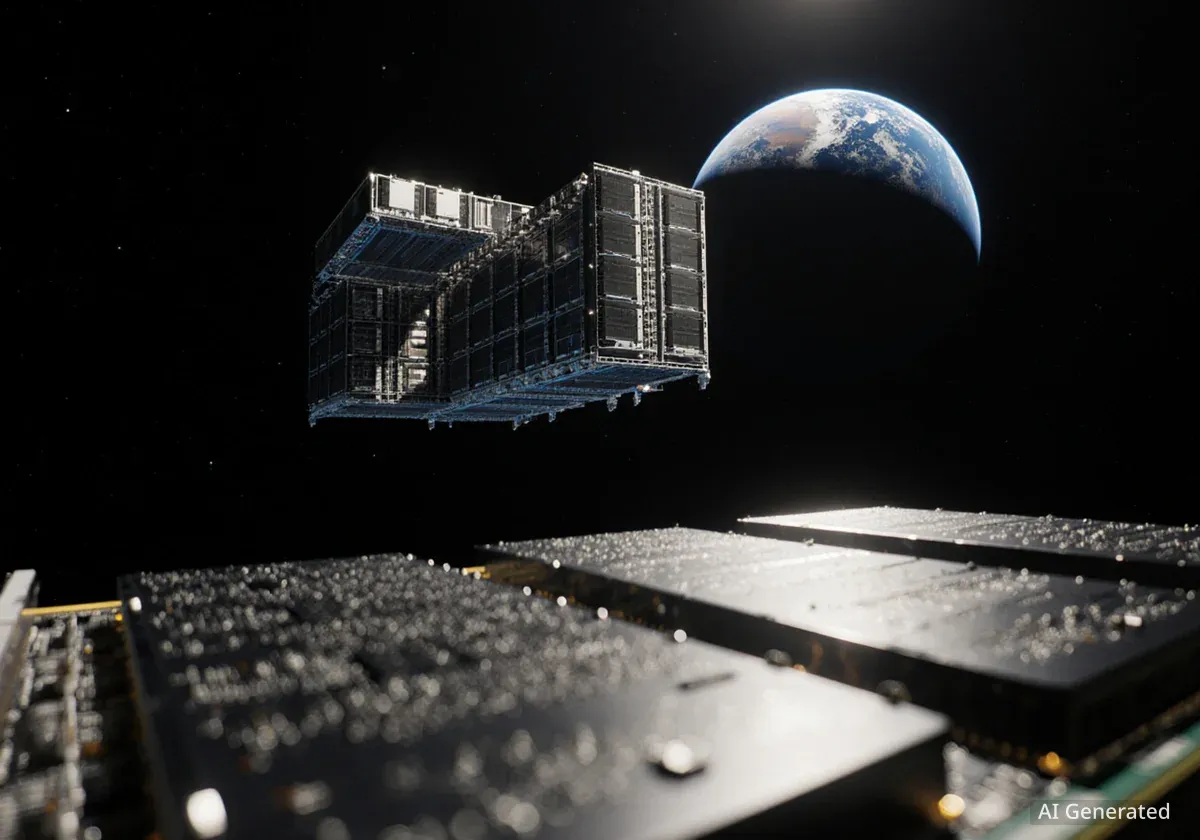

As the artificial intelligence boom strains Earth's power grids, some of the biggest names in technology are looking to space for a solution. The concept of orbiting data centers, powered by the sun, is gaining traction as a long-term answer to AI's insatiable energy demands, though significant engineering hurdles remain.

Companies like SpaceX are already taking preliminary steps, with plans for vast satellite networks that could one day support computing in orbit. The move reflects a growing concern that terrestrial infrastructure may not be able to keep pace with the projected growth of AI, which is expected to drive over $5 trillion in spending on earth-based data centers by the end of the decade.

Key Takeaways

- Tech leaders, including Elon Musk, are proposing orbital data centers to power energy-intensive AI models using solar energy.

- Major obstacles include generating sufficient power, dissipating heat in a vacuum, and the high cost of launching heavy equipment.

- Experts believe small-scale pilot projects may be feasible by 2030, but large-scale deployment remains decades away.

- The push is driven by concerns over strained electrical grids and the rising environmental and financial costs of AI on Earth.

The Growing Pressure for an Off-World Solution

The conversation around space-based data centers has shifted from science fiction to serious business strategy. The rapid expansion of AI has created an unprecedented demand for electricity, pushing existing power grids to their limits and raising environmental concerns.

This has prompted industry leaders to explore alternatives. Elon Musk has been a vocal proponent, suggesting that merging his ventures, xAI and SpaceX, would be essential to building the necessary infrastructure. He has stated that space could become the most economical location for AI computation within two to three years.

Other major players are also exploring the idea. Alphabet CEO Sundar Pichai has mentioned that Google is considering "moonshot" concepts for orbital data centers, while Amazon founder Jeff Bezos has identified them as a potential next step for space-based ventures designed to benefit Earth.

A Response to Earth's Limits

The primary driver for this interest is the physical limitation of our planet's infrastructure. "A lot of smart people really believe that it won’t be too many years before we can’t generate enough power to satisfy what we’re trying to develop with AI," said Jeff Thornburg, CEO of Portal Space Systems and a veteran of SpaceX. This sentiment underscores the urgency behind finding alternative energy sources to sustain technological growth.

The Engineering Challenges of Computing in Orbit

While the concept is compelling, the path to deploying functional data centers in space is filled with formidable technical challenges. Experts agree that the underlying physics are sound, but the engineering required to operate at scale is still in its infancy.

The Power Generation Problem

The first and most significant hurdle is generating enough power. Today's most advanced AI chips require vast amounts of electricity, far more than current satellite technology can provide. Boon Ooi, a professor at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, explained that generating just one gigawatt of power would necessitate a solar array roughly one square kilometer in size.

Furthermore, solar power in orbit is not constant. Satellites pass through Earth's shadow, interrupting power generation. This would require massive onboard batteries to ensure the steady, uninterrupted power that AI chips demand, adding even more weight and complexity to the launches.

Cooling in a Vacuum

Another unresolved issue is heat dissipation. On Earth, data centers use airflow and liquid cooling systems to prevent processors from overheating. These methods are ineffective in the vacuum of space.

"There’s nothing that can take heat away," noted Josep Miquel Jornet, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at Northeastern University. "Researchers are still exploring ways to dissipate that heat."

Without a viable cooling solution, the high-performance GPUs essential for AI would quickly overheat and fail, making any large-scale orbital computing impossible.

A Question of Timeline and Scale

Despite the optimistic predictions from some industry leaders, most experts project a much longer timeline. The consensus is that while small pilot projects could emerge by 2030, they will not be able to replace the massive terrestrial data centers being built today.

So far, achievements have been modest. Only one startup has successfully operated a single high-end Nvidia GPU on a satellite. Reaching the scale of even a small terrestrial data center would require thousands of such satellites working in concert.

Kathleen Curlee, a research analyst at Georgetown University, remains skeptical of the accelerated timelines. "We’re being told the timeline for this is 2030, 2035—and I really don’t think that’s possible," she said, highlighting that the technology is not currently feasible at the proposed scale.

Logistical Hurdles

Beyond power and cooling, other obstacles include managing orbital traffic and communication delays.

- Space Debris: Low Earth orbit is increasingly crowded. Managing a network of thousands or even a million satellites would require sophisticated autonomous collision-avoidance systems to navigate space junk.

- Communication Latency: For many AI applications that require real-time responses, communicating with satellites is slower and less efficient than using fiber-optic connections on the ground. "Fiber connections will always be faster and more efficient than sending every prompt to orbit," Jornet explained.

The Long-Term Vision

Even with the significant challenges, the push for orbital data centers is not expected to fade. The fundamental problem of AI's energy consumption on Earth remains, and space offers a potentially limitless source of solar power.

Jeff Thornburg believes that while the timeline may be longer than some hope, the industry will eventually solve these problems. "I think it’s a minimum of three to five years before you see something that’s actually working properly, and you’re beyond 2030 for mass production," he projected.

He also cautioned against dismissing the idea, particularly given the track record of those involved. "You shouldn’t bet against Elon," he said, referencing SpaceX's history of achieving goals once deemed impossible. As engineers continue to iterate on designs for solar arrays, cooling systems, and launch vehicles, the prospect of moving humanity's digital brain off-world becomes less a matter of if, but when.