China is preparing for a significant increase in space activity before the end of the year, with up to nine new rockets scheduled for their first orbital launch attempts. This push includes major tests for its lunar exploration program and a surge in launches from its rapidly growing commercial space sector, signaling a new phase in the country's space ambitions.

The upcoming launches and tests are the result of a decade-long strategy to foster a competitive domestic space industry. This initiative aims to build the launch capacity needed for national projects, including the development of large satellite mega-constellations.

Key Takeaways

- China plans up to nine maiden rocket launches by the end of the year, including eight from commercial firms and one from a state-owned enterprise.

- Key tests are expected for the Long March 10 rocket and a new crew spacecraft, both essential for China's goal of landing astronauts on the Moon.

- The surge in activity is driven by a 2014 policy decision to open the space sector to private capital, leading to substantial government and private investment.

- Commercial companies like Landspace and Space Pioneer are developing reusable, medium-lift rockets to compete for contracts to launch China's national mega-constellations.

Preparations for Lunar Missions Intensify

A central focus of China's current space efforts is its crewed lunar program, which aims to land astronauts on the Moon by 2030. Several critical hardware tests are anticipated in the coming months. These tests are vital for validating the systems required for the ambitious mission.

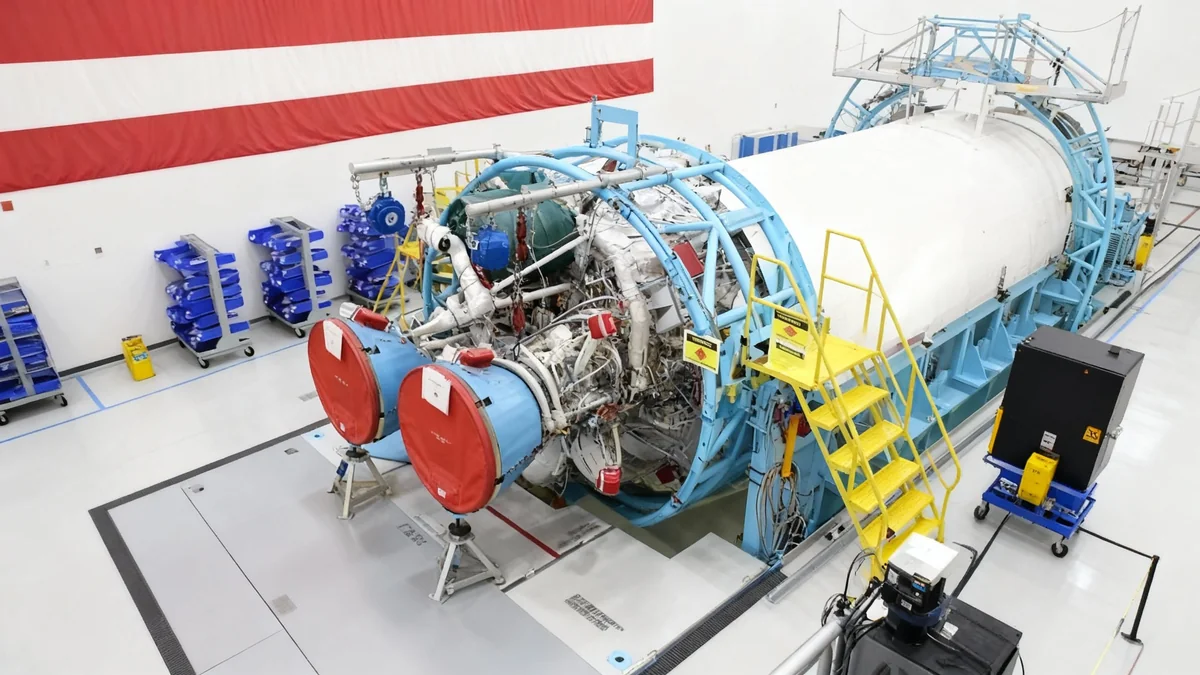

Progress is being watched on the Long March 10, the heavy-lift rocket designed to carry astronauts to lunar orbit. Following a successful static fire test of a shortened first-stage prototype earlier this year, engineers may soon conduct a full-scale first-stage static fire or a low-altitude launch test.

Alongside the rocket, a new-generation crew spacecraft is also undergoing evaluation. An essential upcoming milestone is the in-flight abort test, designed to ensure the crew capsule can safely separate from the rocket during the most intense phase of ascent, known as maximum dynamic pressure (Max-Q). According to space industry analysts, this test could take place at either the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center in the Gobi Desert or the coastal Wenchang Space Launch Site in Hainan.

A Strategic Goal

China's lunar program is a national priority, seen as a demonstration of its technological capabilities. The successful development of the Long March 10 and the new crew vehicle are the two most critical elements needed to achieve its goal of a crewed lunar landing before the end of the decade.

Commercial Launch Sector Enters a New Era

The most visible sign of China's accelerated space activity is the wave of maiden launches from its commercial sector. As many as eight private companies are preparing to fly their new medium-lift rockets for the first time. These companies are vying to establish reliability and secure lucrative contracts.

A Crowded Field of New Rockets

The companies preparing for debut flights include Space Pioneer, Landspace, iSpace, Orienspace, and Galactic Energy. Their goal is to develop reliable, and often reusable, launch vehicles capable of carrying significant payloads to orbit. The state-owned China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC) is also set to debut its Long March 12A, which may attempt a landing test on its first flight.

"The goal is reliability first—reaching orbit—then competing for contracts for China’s mega-constellations. Those contracts could provide their long-term business foundation," noted Andrew Jones, a correspondent covering China's space program.

These initial launches carry high risks. As new companies test complex liquid-propellant systems for the first time, both spectacular successes and failures are possible. This period will be a crucial test for the viability of China's commercial space ecosystem.

The Rise of Private Investment

The surge in commercial activity follows a 2014 government decision to allow private capital into the space industry. This has led to massive funding rounds, with companies like Space Pioneer and Landspace each raising over $300 million to develop their launch vehicles.

Driving Force Behind the Expansion

The current push is rooted in strategic national objectives, primarily the need to build out large-scale satellite networks. China is planning at least two mega-constellations, known as Guowang and G60 Starlink, which will require thousands of satellites to be launched in the coming years.

The existing fleet of state-operated Long March rockets does not have the capacity or cost-effectiveness to deploy these constellations efficiently. Recognizing this gap, the Chinese government has encouraged private companies to fill the void. Local and provincial governments have also invested heavily, creating space industry hubs to attract talent and capital.

- Policy Shift: In 2014, China opened its space sector to private investment, inspired by the success of companies like SpaceX in the United States.

- Market Demand: The primary market for these new rockets is the launch contracts for national satellite mega-constellations.

- Technological Evolution: Many firms are moving directly to developing reusable, stainless steel rockets similar in class to SpaceX's Falcon 9.

This state-guided, market-driven approach has transformed China's launch industry in less than a decade, moving from a handful of startups to a dynamic sector with multiple companies on the verge of orbital capability.

New Capabilities in Orbit

Beyond launch, China is also demonstrating increasingly sophisticated capabilities in space. A recent exchange of satellite imagery highlighted a new aspect of geopolitical competition in orbit between the U.S. and China.

Earlier this year, a satellite operated by the American company Maxar captured a high-resolution, non-Earth image of a Chinese Shijian-26 experimental satellite from a distance of approximately 50 kilometers. This type of on-orbit inspection capability is rarely demonstrated publicly.

In a direct response, Chang Guang Satellite Technology, a Chinese company, used one of its Jilin-1 observation satellites to capture a similar image of a Maxar satellite. This act of reciprocity signaled that Chinese operators also possess advanced on-orbit imaging and maneuvering capabilities.

This "cat-and-mouse" dynamic, previously observed with inspector satellites in geostationary orbit, is now extending to low Earth orbit. The public sharing of these images suggests growing confidence from both nations in their respective space-domain awareness technologies.