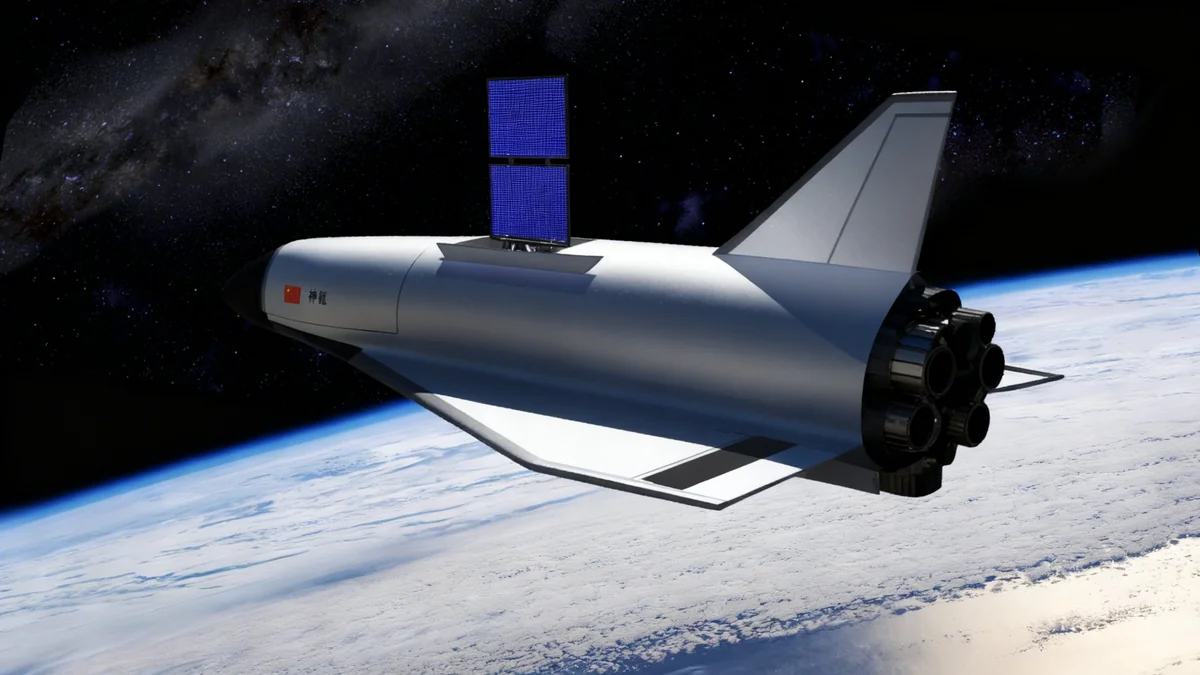

A new kind of construction boom is quietly reshaping the Arctic. Driven by escalating geopolitical competition and a surge in polar-orbiting satellites, nations and private companies are racing to build ground stations across the high north. These facilities, crucial for communicating with satellites, are turning remote towns into strategic hubs in a modern space race.

From the oil fields of Alaska to the tundra of northern Canada and Scandinavia, the demand for reliable satellite communication links is transforming the region. This expansion is not just about commercial data; it's a critical component of national security, military surveillance, and monitoring the effects of climate change in one of the world's most sensitive areas.

Key Takeaways

- A surge in polar-orbiting satellites is driving intense demand for Arctic ground stations.

- Geopolitical tensions between the US, China, and Russia are fueling the construction of new satellite infrastructure for military and surveillance purposes.

- Remote locations like Deadhorse, Alaska, and Inuvik, Canada, are becoming vital strategic communication hubs.

- Logistical challenges include extreme weather, thawing permafrost, and the vulnerability of undersea data cables.

The New Northern Frontier for Space Communication

The primary advantage of the Arctic is its geography. A satellite in a polar orbit passes over the Earth's poles on every revolution, making it possible to communicate with it far more frequently from a northern ground station.

"You can see a satellite 14-plus times a day," explained Ron Faith, CEO of RBC Signals, a company operating in the region. This is a significant increase compared to mid-latitude locations, where the same satellite might only be visible four times daily. This high frequency is essential for operators who need to download vast amounts of data quickly and reliably.

This has turned unlikely places like Deadhorse, Alaska, into a hotbed of activity. Primarily an industrial camp for the Prudhoe Bay oil field, Deadhorse now hosts eight antennas for RBC Signals and a facility for Amazon's AWS Ground Station network. The key is existing infrastructure. "You can only put satellite dishes where there’s fiber," said Christopher Richins, founder of RBC Signals. "Otherwise, the data comes down, and it’s got nowhere to go."

Geopolitical Stakes in the High North

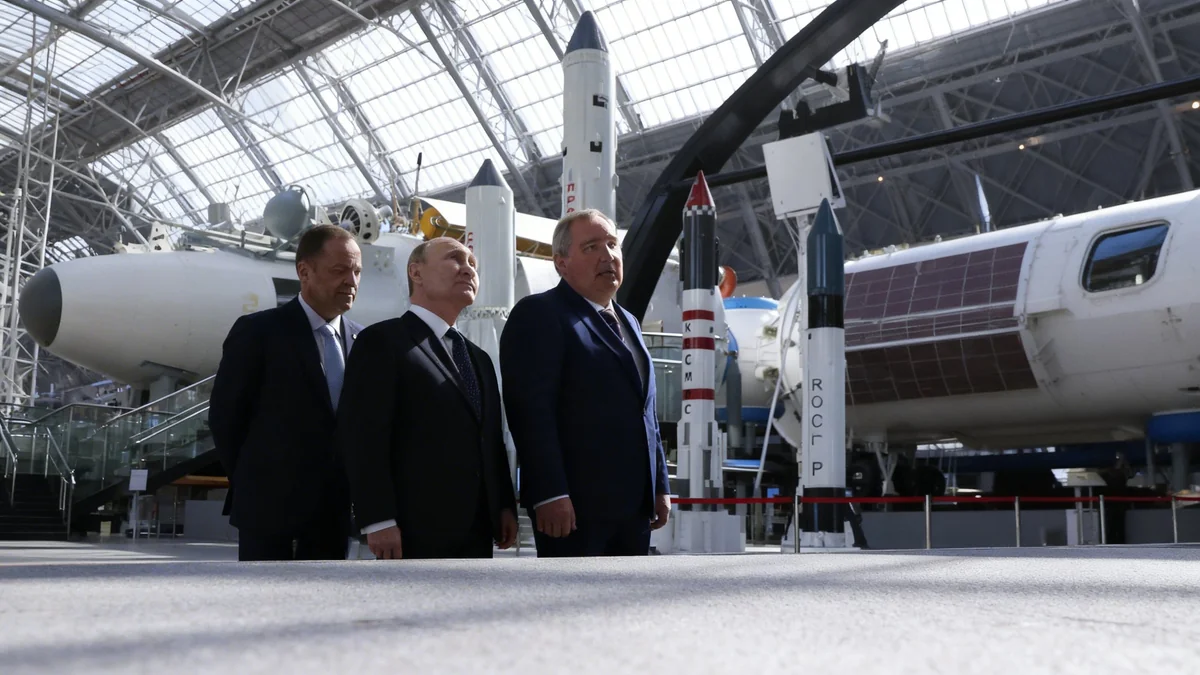

The commercial demand is matched, and often surpassed, by government and military interests. The Arctic is a critical corridor for intercontinental ballistic missiles, making satellite surveillance a top priority for national defense.

"If China or Russia were to launch intercontinental ballistic missiles, all of that is going to fly over the North Pole," stated Pierre Leblanc, a retired Canadian Armed Forces colonel. "It’s very important to have a lot of sensors that are going to be monitoring that area."

The United States is heavily invested. The U.S. Space Force has awarded multi-billion dollar contracts for polar-orbiting satellites. Northrop Grumman has a deal worth over $4.1 billion to build two such satellites by 2031, while Boeing secured a $2.8 billion contract for its own set. These systems are designed to provide persistent surveillance and communication capabilities in a strategically vital region.

Arctic Satellite Hubs

- Svalbard, Norway: Home to Svalsat, the world's largest polar ground station. However, a 1920 treaty restricts its use for military purposes.

- Inuvik, Canada: A growing hub with facilities used by Canadian, French, German, and Swedish governments.

- Deadhorse, Alaska: A key U.S. location with private operators like RBC Signals and Amazon Web Services.

- Piteå, Sweden: Arctic Space Technologies has rapidly expanded from one antenna in 2022 to 35 today, with plans for more.

Expanding Infrastructure Across the Arctic Circle

The rush for Arctic real estate is evident across multiple countries. In Canada, the town of Inuvik in the Northwest Territories has become a major center. The government-owned Inuvik Satellite Station Facility recently added five new dishes, bringing its estimated total to 13. "Canada is setting up another dish because their dish is full," said Mayor Peter Clarkson, highlighting the intense demand.

Private ventures are also expanding. C-Core, another operator in Inuvik, announced plans to grow its footprint to better serve Canadian missions. Local entrepreneur Tom Zubko, who runs New North Networks, has acquired land for another ground station, noting, "China satellites are flying over the top of us every hour or so. And Russian satellites are doing the same."

Across the Atlantic, Sweden and Norway are also key players. Arctic Space Technologies, based in Piteå, Sweden, serves government and commercial clients like Viasat and Eutelsat. In Norway, the Svalbard archipelago hosts the massive Svalsat station, but its military limitations and reliance on a single subsea cable create vulnerabilities that drive demand for alternative sites on the mainland.

"We will see more ground stations, we’ll see more dishes at existing ground stations, we’ll see more cables to provide redundancy."

- Michael Byers, University of British Columbia professor

Challenges of Building on Shifting Ground

Operating in the Arctic is not without significant challenges. The harsh environment requires specialized construction. Antennas must be enclosed in radomes—large, dome-like structures—to protect them from extreme cold, wind, and snow.

These structures are often mounted on heated sheds built on steel pilings drilled up to 45 feet into the ground. This is a necessary precaution against thawing permafrost, a growing concern due to climate change, which could destabilize the foundations.

The Rise of Inter-Satellite Links

A potential disruptor to the ground station boom is the development of inter-satellite laser communication. This technology allows satellites to relay data to each other in orbit before sending it down to Earth. While this could reduce the need for geographically remote ground stations, experts believe the sheer volume of data will still require the high-bandwidth capabilities of terrestrial fiber optic connections, ensuring Arctic stations remain relevant for the foreseeable future.

Wildlife and security are also factors. During the construction of one facility, workers arrived to find a grizzly bear had taken shelter inside an unfinished structure. Fences and locked doors are now standard. Furthermore, the reliance on undersea fiber optic cables presents a security risk, as demonstrated by suspected sabotage incidents involving cables in the Baltic Sea.

Despite these hurdles and the advent of new technologies like inter-satellite links, the demand for Arctic ground stations shows no sign of slowing. As more satellites are launched into polar orbits, the strategic value of these cold, remote outposts will only continue to grow, solidifying their role as the nerve centers of a new global information and security network.