Researchers have developed a new protocol for fault-tolerant quantum computation that dramatically reduces the resources required, a significant step toward building practical, large-scale quantum computers. The new method achieves a constant space overhead and a polylogarithmic time overhead, meaning future quantum machines could be built with far fewer physical components and run complex calculations exponentially faster than previously thought possible with such efficient designs.

This development addresses one of the most persistent challenges in the field: the immense physical resources needed to protect fragile quantum information from errors. By combining two established quantum error-correction techniques, the protocol offers a path to building powerful quantum computers that are not only more efficient but also account for the real-world processing time of classical support systems.

Key Takeaways

- A new hybrid protocol for fault-tolerant quantum computation (FTQC) has been established.

- It achieves constant space overhead, meaning the number of physical qubits needed per logical qubit does not grow with the problem size.

- The protocol also achieves polylogarithmic time overhead, representing a major speedup over previous constant-space methods.

- For the first time in this context, the analysis rigorously includes the processing time of classical computers, making the model more realistic.

- The method combines non-vanishing-rate Quantum Low-Density Parity-Check (QLDPC) codes with concatenated Steane codes.

The Quantum Overhead Problem

Quantum computers hold the promise of solving problems intractable for even the most powerful supercomputers. However, the quantum bits, or qubits, that power them are extremely fragile and susceptible to environmental noise, which introduces errors into calculations.

To overcome this, scientists use quantum error-correcting codes to create robust "logical qubits" from many physical qubits. This process, known as fault-tolerant quantum computation (FTQC), ensures calculations remain accurate. But it comes at a cost.

This cost is measured in two ways: space overhead and time overhead. Space overhead refers to the number of physical qubits required to create a single stable logical qubit. Time overhead is the ratio of how many physical operations are needed to perform a single logical operation—essentially, how much the computation slows down.

A Fundamental Trade-Off

Historically, quantum computing architectures have faced a difficult trade-off. Protocols like those using surface codes or concatenated codes could achieve fast, polylogarithmic time overheads, but this required a polylogarithmic space overhead, meaning the number of physical qubits would need to grow as problems became more complex. Conversely, newer approaches using non-vanishing-rate codes achieved a desirable constant space overhead, but at the cost of a much slower, polynomial time overhead. This new research breaks that long-standing compromise.

A Hybrid Solution Emerges

The new protocol, developed by a team of researchers including Shiro Tamiya, Masato Koashi, and Hayata Yamasaki, resolves this space-time conflict by creating a hybrid system. It leverages the strengths of two different types of quantum error-correcting codes.

In this architecture, Quantum Low-Density Parity-Check (QLDPC) codes, specifically a type known as quantum expander codes, are used as the primary registers. These codes are excellent for storing and protecting quantum information with a high density, which is key to achieving the constant space overhead.

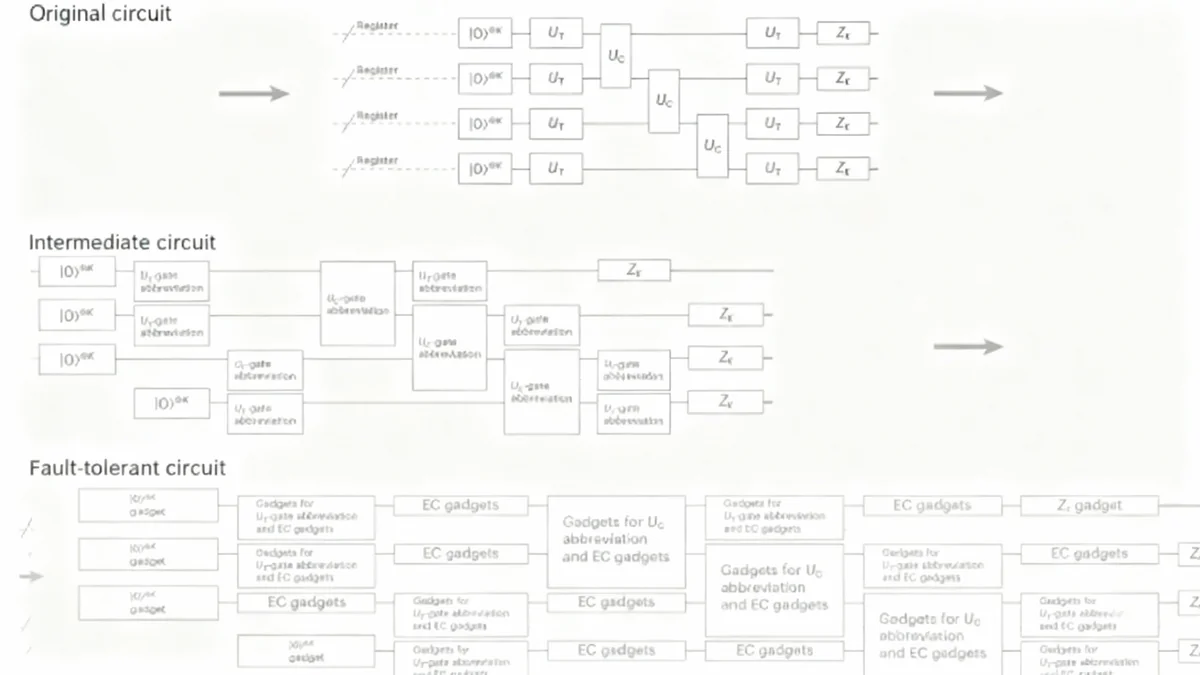

However, performing universal quantum gates on these QLDPC-encoded qubits is complex. To solve this, the researchers use a different method—concatenated Steane codes—to prepare special auxiliary states. These states are then used to perform logical operations on the main QLDPC registers via a process called gate teleportation.

How the Hybrid System Works

- Memory: Logical qubits are stored in robust QLDPC code blocks, which require only a constant number of physical qubits per logical qubit.

- Operations: To perform a calculation, auxiliary states are prepared using the well-established concatenated Steane code protocol.

- Execution: These auxiliary states enable logical gates to be teleported onto the QLDPC memory blocks, executing the desired computation.

This division of labor is crucial. The Steane code protocol, while less space-efficient, is used only for temporary state preparation. The highly efficient QLDPC codes handle the long-term storage, allowing the overall system to maintain a constant space footprint.

Achieving High Parallelism for Speed

A significant reason this new method achieves such a dramatic speedup is its ability to perform many logical operations in parallel. Previous constant-space protocols were limited in how many logical qubits could be operated on simultaneously, creating a bottleneck that led to polynomial time overhead.

The new analysis shows that the quantum expander codes used for memory can function effectively even at smaller sizes, scaling only polylogarithmically with the problem size. This reduction in the resource requirement for each code block frees up resources to run more logical operations at the same time.

By increasing this parallelism, the protocol allows for operations on a much larger number of logical qubits at each time step. This increased throughput is what reduces the time overhead from polynomial to the much faster polylogarithmic scale.

A More Realistic Approach to Fault Tolerance

One of the most important contributions of this work is its rigorous inclusion of classical computing time. In any real-world quantum computer, classical processors are needed to decode error syndromes and determine the necessary corrections. Many theoretical models have assumed this classical processing happens instantaneously.

This assumption is a significant oversimplification. Decoding algorithms take time, and during this wait, qubits continue to be exposed to noise, accumulating more errors. This "backlog problem" could potentially undermine the entire fault-tolerant system or even make it infeasible.

"To fully analyse the overhead achievable in FTQC, it is essential to incorporate the waiting time for noninstantaneous classical computations into the analysis... the decoding runtime, which has often been considered negligible in theoretical analyses, can dominate the asymptotic scaling."

The researchers explicitly accounted for this by building wait times into their fault-tolerant circuit. They proved that a threshold for fault tolerance still exists even with these delays, provided the decoding algorithm meets specific criteria. They confirmed that the "small-set-flip decoder" used for quantum expander codes satisfies these requirements, ensuring that the classical processing time remains manageable and does not compromise the system's performance or overheads.

Completing the Proof with New Techniques

To construct their proof, the team also introduced a new analytical method called "partial circuit reduction." Proving fault tolerance across an entire complex quantum circuit is incredibly difficult due to potential error correlations between different parts of the system.

Partial circuit reduction allows for a modular analysis. Instead of tackling the whole circuit at once, it examines smaller segments, or "rectangles," one by one. This method formally replaces a noisy segment with an ideal, error-free version while updating the error probabilities for the rest of the circuit. This systematic, step-by-step approach provided a complete and rigorous proof of the threshold theorem for this type of protocol, closing a logical gap in previous analyses.

Implications for the Future of Quantum Computing

This research provides a robust theoretical foundation for building more practical and efficient quantum computers. By demonstrating that constant space and polylogarithmic time overheads are simultaneously achievable, it redraws the map of what is possible in quantum architecture design.

The use of well-studied components like quantum expander codes and concatenated Steane codes is also promising for implementation. Both have been subjects of active experimental research, with small-scale demonstrations already underway in physical systems like neutral atoms and trapped ions.

By providing a comprehensive blueprint that accounts for every potential bottleneck, including classical computation, this work establishes a clear path forward. It suggests that the immense overheads once seen as an unavoidable price for quantum power may be overcome, bringing the era of large-scale, fault-tolerant quantum computation one step closer to reality.