With the International Space Station (ISS) scheduled for retirement around 2030, NASA is supporting the development of commercial replacements to maintain a U.S. presence in low Earth orbit. However, experts are concerned that the agency's current safety verification methods, inherited from past government-led programs, could create significant delays and hinder the growth of a private space economy.

Key Takeaways

- The International Space Station is expected to be decommissioned by 2030, creating an urgent need for commercial successors.

- NASA is using a rigid "certification" process for new private stations, similar to the one that caused delays in the Commercial Crew Program.

- Industry experts advocate for a more flexible "qualification" model, which verifies safety based on agreed-upon contractual standards.

- Continuing with the current approach risks a gap in U.S. orbital presence and could give a strategic advantage to competitors like China.

The Transition to Commercial Orbit

For decades, habitable space stations have been the exclusive domain of government agencies. The upcoming retirement of the ISS marks a major shift towards a new model where private companies will own and operate orbital platforms. This transition is driven by falling launch costs and a growing demand for space-based research and manufacturing from both public and private sectors.

To ensure a continuous American presence in space, NASA has initiated programs to foster this new commercial ecosystem. The agency is actively working with private industry through its Commercial LEO Destinations (CLD) program and a separate Space Act Agreement with Axiom Space.

NASA's Commercial Initiatives

Two primary efforts are underway to develop private space stations. The CLD program is a public-private partnership involving multiple companies to create independent stations. The agreement with Axiom Space involves attaching a commercial module to the ISS, which will later detach to become a free-flying station before the ISS is deorbited.

These new stations will serve a variety of customers. NASA plans to be a primary tenant, leasing space for its astronauts to conduct research. Other potential clients include international space agencies, industrial manufacturers, and even space tourists.

Lessons from the Commercial Crew Program

The move to private stations requires NASA to redefine its oversight role, particularly concerning astronaut safety. A key point of reference is the Commercial Crew Program (CCP), which developed private spacecraft to transport astronauts to the ISS after the Space Shuttle's retirement.

Under CCP, NASA applied a stringent "human rating" certification process based on legacy government standards. This approach mandated specific design features, such as increased redundancy and particular abort systems, which went beyond the companies' initial plans.

"Application of these stringent demands affected proposed design specifications, number and types of verification testing, and operational demonstrations," the original analysis noted, leading to significant program adjustments.

These requirements contributed to substantial delays and cost increases. SpaceX's first crewed mission in May 2020 occurred nearly four years after its initial target and more than a decade after the shuttle retired. During this gap, NASA remained dependent on purchasing seats from Russia. Meanwhile, Boeing's Starliner vehicle has yet to complete its final test flight to be certified for regular astronaut transport.

The Debate Over Safety Verification

The central issue facing the new commercial stations is how NASA will ensure they are safe for its astronauts. The agency appears set to apply the same certification model used for CCP, but critics argue this is a fundamental mismatch for facilities that NASA will not own or operate.

Certification: A Government-Centric Model

Certification is a top-down process where a government agency imposes a pre-established set of rules and requires documented proof of compliance. This system was designed for government-owned assets like the Space Shuttle. Applying it to private enterprise creates several challenges:

- Ownership and Control: NASA would be certifying systems it does not own, raising questions about its authority and the operator's accountability.

- Liability: It complicates the allocation of risk and liability between the government and private operators.

- Statutory Authority: Unlike the FAA, which has congressional authority to regulate commercial spaceflight, NASA has not been granted the power to certify private space facilities.

Qualification: A Partnership Approach

An alternative model is qualification. In this framework, safety and performance standards are defined in a contract between NASA and the commercial provider. The company then demonstrates it can meet these requirements, potentially using its own proven methods and industry best practices.

A qualification approach allows commercial companies to propose innovative solutions to meet safety goals, rather than adhering to a rigid, pre-defined government checklist. This can lead to faster development and lower costs while still ensuring astronaut safety through mutually agreed-upon standards.

This approach treats NASA as a customer with specific needs, rather than a regulator imposing universal rules. The company is responsible for delivering a service that meets the contractual requirements, giving it more flexibility in design and operations.

Risks of the Current Path

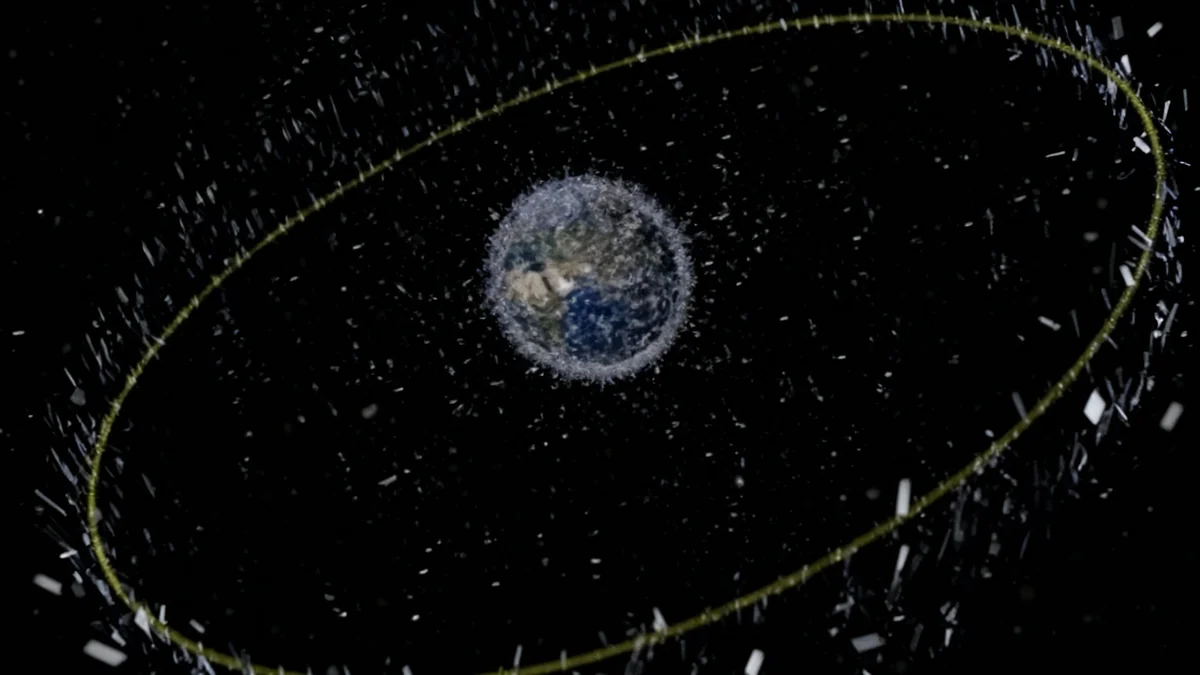

Continuing with a certification-based model for commercial stations presents significant risks that could undermine the very goals of the CLD program. The most immediate concern is the potential for a capability gap in low Earth orbit.

If commercial stations are not ready by the time the ISS is decommissioned, the U.S. could lose its access to an orbital laboratory. The Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel has already warned that legacy certification processes could prevent new facilities from being ready in time. Such a gap would disrupt vital scientific research and hand a strategic advantage to competitors, especially China, which is actively expanding its own space station and attracting international partners.

Market Distortion and Stifled Innovation

Beyond the schedule risk, NASA's certification process could inadvertently distort the emerging market. By creating a "NASA-certified" designation, the agency might imply that uncertified stations are unsafe, even if they meet rigorous industry standards.

This perception could create several negative effects:

- It could discourage non-government customers from using stations that lack NASA's stamp of approval.

- It may cause investors to hesitate, viewing uncertified platforms as a higher regulatory risk.

- It could limit competition by favoring companies that are part of NASA's program, potentially stifling innovation from other providers.

For a healthy commercial LEO economy to develop, a diverse range of providers and platforms is needed. A process that favors a select few could slow the growth of this nascent industry.

A Call for a New Framework

To avoid these pitfalls, experts suggest NASA should shift its role from a top-down regulator to a strategic partner. This involves moving away from the Apollo-era certification mindset and embracing a collaborative qualification framework.

By clearly defining its safety requirements as a customer and working with commercial partners to meet them, NASA can ensure the well-being of its astronauts without imposing undue burdens on the industry. This partnership model would allow private companies to innovate and operate efficiently while still meeting the high standards required for human spaceflight.

Ultimately, the success of the transition to a commercialized low Earth orbit depends on flexible, forward-looking governance. Adopting a qualification-based approach would empower private industry, safeguard U.S. interests in space, and foster the development of a resilient and competitive orbital economy.