In a desert expanse overlooking the Arabian Sea, Oman is laying the groundwork for a major spaceport, a strategic move to diversify its economy beyond oil and establish itself as a key player in the rapidly growing global space industry. The project, led by the company Etlaq, aims to capitalize on the increasing demand for satellite launch services, a market currently valued at over $630 billion.

Located near the special economic zone of Duqm, the facility is designed to support a range of missions, from small suborbital research rockets to heavy orbital launch vehicles. If successful, Oman will join a select group of just a dozen nations with orbital launch capabilities, positioning itself as the primary commercial launch hub for the Middle East and Africa.

Key Takeaways

- Oman is developing a major commercial spaceport near Duqm, operated by the company Etlaq.

- The project is part of Oman's Vision 2040 plan to diversify its economy as oil reserves are projected to run out in approximately 15 years.

- Oman's equatorial location and open sea access provide significant geographical advantages for rocket launches.

- The global demand for satellite launches has increased by roughly 500% in five years, creating a bottleneck that Oman aims to fill.

- Early suborbital launches have faced delays, highlighting the technical challenges of developing a new space program.

A Growing Need for Space Access

The global space industry is experiencing unprecedented growth. In 2018, 452 objects were sent into space. Just five years later, that number surged to 2,895. This explosion in satellite deployment, driven by communications, Earth observation, and scientific research, has strained the world's existing launch infrastructure.

Currently, there are only 22 active orbital launch sites worldwide, with more than half located in the United States, Russia, or China. This concentration creates a significant bottleneck for smaller countries and private companies seeking to deploy their own technology into orbit.

Launch Demand by the Numbers

- $630 billion: Estimated value of the global space industry in 2023.

- 500%: Approximate increase in objects launched into space between 2018 and 2023.

- 1 year+: Current typical wait time for a rideshare launch with major providers like SpaceX.

James Causey, executive director of the Global Spaceport Alliance, noted that the demand for launches is continuing to grow. This supply-demand imbalance creates a clear market opportunity for new entrants. For Omani companies like ETCO Space, which develops satellites, having a domestic launch site is a game-changer. Its CEO, Abdulaziz Jaafar, pointed out that the minimum wait time to launch with a major provider can be four to eight months, and often much longer.

Oman's Strategic Advantages

Oman possesses a unique combination of geography and political stability that makes it an ideal location for a spaceport. Often referred to as the “Switzerland of the Middle East,” the nation’s neutrality makes it an attractive partner for international collaboration.

The Equatorial Edge

The Etlaq site is located at 18 degrees north latitude, placing it very close to the equator. Launching from near the equator provides a natural boost from the Earth's rotational speed, which is fastest there. This effect helps rockets conserve fuel and allows for more flexibility in placing satellites into various orbits.

“The lower your latitude, the more range of orbits you can have,” explained Jim Cantrell, a former SpaceX executive and current CEO of launch startup Phantom Space.

This equatorial advantage is significant. The European Space Agency’s primary spaceport in French Guiana is prized for its proximity to the equator, and Etlaq’s location is similarly advantageous compared to U.S. sites like Cape Canaveral, which sits at 28 degrees north.

Safety and Location

Another critical factor is what happens when launches go wrong. Rocket parts often fall back to Earth, making it essential to have a large, unpopulated area for debris. The Omani spaceport opens directly onto the vast and empty Arabian Sea, providing a safe drop zone. This contrasts with other regional powers like the UAE or Saudi Arabia, where potential debris could fall into densely trafficked shipping lanes like the Strait of Hormuz or populated areas.

Vision 2040: A Post-Oil Future

The spaceport is a cornerstone of Oman's Vision 2040 program, a national strategy to transition away from a fossil fuel-based economy. With its oil reserves expected to be depleted within 15 years, the government is aggressively investing in technology, green energy, agriculture, and fishing. The goal is to increase the tech economy's contribution to GDP from just 2% in 2024 to 10% by 2040. The space program, established by royal decree in 2020, is central to this ambition.

Building an Ecosystem from Scratch

While Oman has the location, it currently lacks the domestic expertise for a large-scale space program. The government and private companies are actively working to bridge this knowledge gap by attracting foreign investment and fostering local talent.

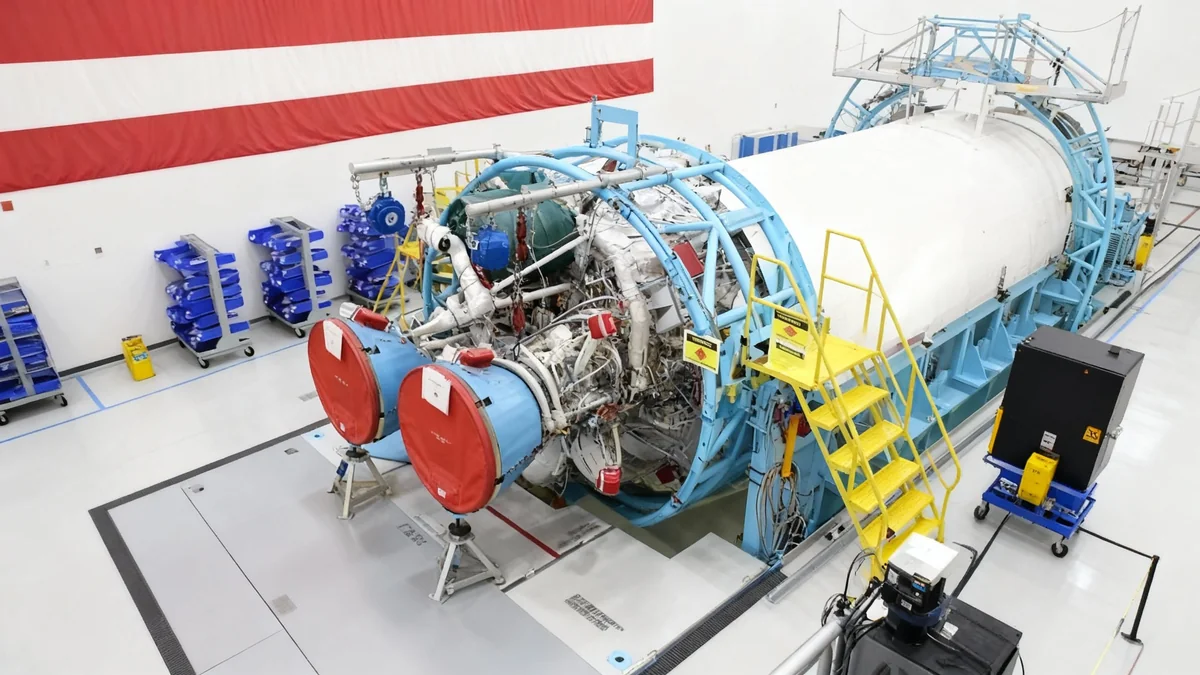

The National Aerospace Services Company (NASCOM), a private entity with close government ties, is spearheading the Etlaq project. Its strategy involves starting with simpler, suborbital missions to build capacity before moving to more complex orbital launches.

“The idea is to host as many launches as safely possible,” said Julanda Al-Riyami, chief commercial officer at Etlaq. “We can work with orbital launchers, but we’re choosing to work with the simpler missions as we build capacity.”

Foreign partnerships are crucial. Cantrell's Phantom Space, for example, plans to mass-produce satellites in Oman, training local engineers and technicians in the process. This exchange provides Phantom Space with lower labor and material costs while facilitating essential knowledge transfer to the Omani workforce.

The Challenges of Getting Off the Ground

The road to space is never smooth. Etlaq's initial “Genesis Program” of suborbital launches has already encountered the harsh realities of rocket science. The first successful launch, Duqm-1, took place in December 2024, sending a 6.5-meter research rocket to the edge of the atmosphere.

However, subsequent planned launches in 2025 have faced setbacks. A public event in April, meant to culminate in the launch of the Horus 4 rocket by private firm Advanced Rocket Technologies (ART), was cancelled due to high winds. Later, a technical issue was discovered, scrubbing the mission entirely.

Another launch in July, involving a rocket from a New Zealand-based company, was also aborted after a pre-flight check revealed a problem with a critical component. These delays make it unlikely Etlaq will meet its initial goal of five launches in 2025.

“Space is hard. Murphy’s law always applies. If it can go wrong, it bloody well will,” commented John Sheldon, a space consultant with nearly three decades of experience.

Those involved in the project remain pragmatic, viewing these early challenges as valuable learning experiences. Ammar Al-Rawahi, a key figure in Oman’s space program, emphasized the country's deliberate approach. “The good thing is that Oman is moving wisely,” he said. By starting with smaller, lower-stakes missions, mistakes become opportunities for growth rather than catastrophic failures.

As Oman pushes forward with its ambitious desert spaceport, it is not just building launchpads and mission control centers. It is methodically constructing a new pillar for its future economy, one launch—and one lesson—at a time.